The Inconvenient Truth of Herman Daly: There is No Economy Without Environment

In an age of climate chaos and economic crisis, Herman Daly's ideas that inspired a movement to live within our means are increasingly essential.

Herman Daly had a flair for stating the obvious. When an economy creates more costs than benefits, he called it “uneconomic growth.” But you won’t find that conclusion in economics textbooks. Even suggesting that economic growth could cost more than it’s worth can be seen as economic heresy.

The renegade economist, known as the father of ecological economics and a leading architect of sustainable development, died on Oct. 28, 2022, at the age of 84. He spent his career questioning economics disconnected from an environmental footing and moral compass.

The seeds of an ecological economist

Herman Daly grew up in Beaumont, Texas, the ground zero of the early 20th-century oil boom. He witnessed the unprecedented growth and prosperity of the “gusher age” set against the poverty and deprivation that lingered after the Great Depression. To Daly, as many young men then and since believed, economic growth was the solution to the world’s problems, especially in developing countries. To study economics in college and export the northern model to the global south was seen as a righteous path.

But Daly was a voracious reader, a side effect of having polio as a boy and missing out on the Texas football craze. Outside the confines of assigned textbooks, he found a history of economic thought steeped in rich philosophical debates on the function and purpose of the economy.

Unlike the precision of a market equilibrium sketched on the classroom blackboard, the real-world economy was messy and political, designed by those in power to choose winners and losers. He believed that economists should at least ask: Growth for whom, for what purpose and for how long?

Daly’s biggest realization came through reading marine biologist Rachel Carson’s 1962 book “Silent Spring,” and seeing her call to “come to terms with nature … to prove our maturity and our mastery, not of nature but of ourselves.” By then, he was working on a Ph.D. in Latin American development at Vanderbilt University and was already quite skeptical of the hyperindividualism baked into economic models. In Carson’s writing, the conflict between a growing economy and a fragile environment was blindingly clear.

The economy depends on the environment. Economics can seem to forget that point.

After a fateful class with Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen, Daly’s conversion was complete. Georgescu-Roegen, a Romanian-born economist, dismissed the free market fairy tale of a pendulum swinging back and forth, effortlessly seeking a natural state of equilibrium. He argued that the economy was more like an hourglass, a one-way process converting valuable resources into useless waste.

Daly became convinced that economics should no longer prioritize the efficiency of this one-way process but instead focus on the “optimal” scale of an economy that the Earth can sustain. Just shy of his 30th birthday in 1968, while working as a visiting professor in the poverty-stricken Ceará region of northeastern Brazil, Daly published “On Economics as a Life Science.”

His sketches and tables of the economy as a metabolic process, entirely dependent on the biosphere as source for sustenance and sink for waste, were the road map for a revolution in economics.

Economics of a full world

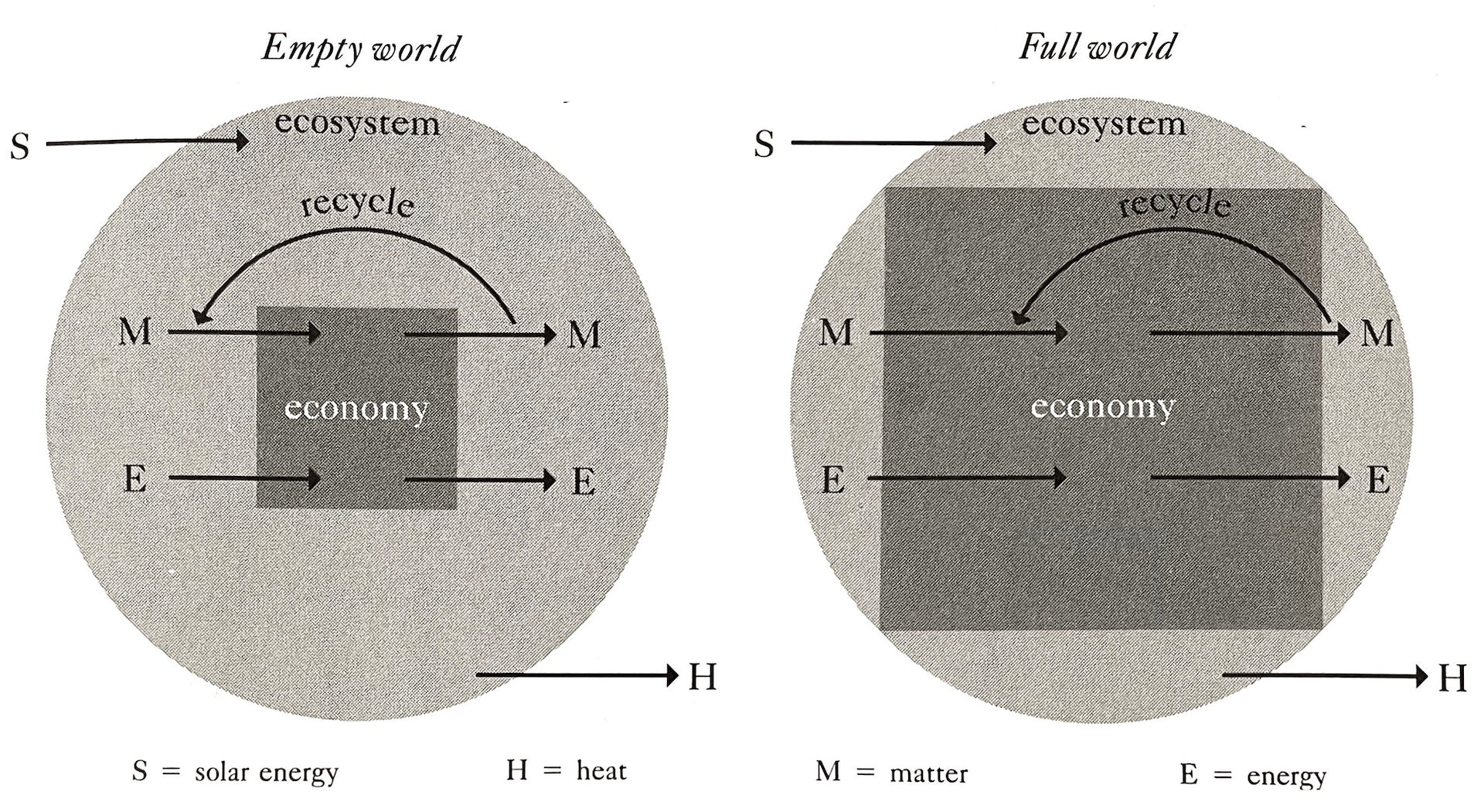

Daly spent the rest of his career drawing boxes in circles. In what he called the “pre-analytical vision,” the economy – the box – was viewed as the “wholly owned subsidiary” of the environment, the circle.

When the economy is small relative to the containing environment, a focus on the efficiency of a growing system has merit. But Daly argued that in a “full world,” with an economy that outgrows its sustaining environment, the system is in danger of collapse.

“That’s not the right way to look at it.”

While a professor at Louisiana State University in the 1970s, at the height of the U.S. environmental movement, Daly brought the box-in-circle framing to its logical conclusion in “Steady-State Economics.” Daly reasoned that growth and exploitation are prioritized in the competitive, pioneer stage of a young ecosystem. But with age comes a new focus on durability and cooperation. His steady-state model shifted the goal away from blind expansion of the economy and toward purposeful improvement of the human condition.

The international development community took notice. Following the United Nations’ 1987 publication of “Our Common Future,” which framed the goals of a “sustainable” development, Daly saw a window for development policy reform. He left the safety of tenure at LSU to join a rogue group of environmental scientists at the World Bank.

“ask the naive, honest questions”

For the better part of six years, they worked to upend the reigning economic logic that treated “the Earth as if it were a business in liquidation.” He often butted heads with senior leadership, most famously with Larry Summers, the bank’s chief economist at the time, who publicly waved off Daly’s question of whether the size of a growing economy relative to a fixed ecosystem was of any importance. The future U.S. treasury secretary’s reply was short and dismissive: “That’s not the right way to look at it.”

But by the end of his tenure there, Daly and colleagues had successfully incorporated new environmental impact standards into all development loans and projects. And the international sustainability agenda they helped shape is now baked into the U.N. Sustainable Development Goals of 193 countries, “a plan of action for people, planet and prosperity.”

In 1994, Daly returned to academia at the University of Maryland, and his life’s work was recognized the world over in the years to follow, including by Sweden’s Right Livelihood Award, the Netherlands’ Heineken Prize for Environmental Science, Norway’s Sophie Prize, Italy’s Medal of the Presidency, Japan’s Blue Planet Prize and even Adbuster’s person of the year.

Today, the imprint of his career can be found far and wide, including measures of the Genuine Progress Indicator of an economy, new Doughnut Economics framing of social floors within environmental ceilings, worldwide degree programs in ecological economics and a vibrant degrowth movement focused on a just transition to a right-sized economy.

I knew Herman Daly for two decades as a co-author, mentor and teacher. He always made time for me and my students, most recently writing the foreword to my upcoming book, “The Progress Illusion: Reclaiming Our Future from the Fairytale of Economics.” I will be forever grateful for his inspiration and courage to, as he put it, “ask the naive, honest questions” and then not be “satisfied until I get the answers.”

Jon D. Erickson, Professor of Sustainability Science and Policy, University of Vermont

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Cover photo: Ines Lee Photos/Moment via Getty Images

Comments ()