The Death Zone

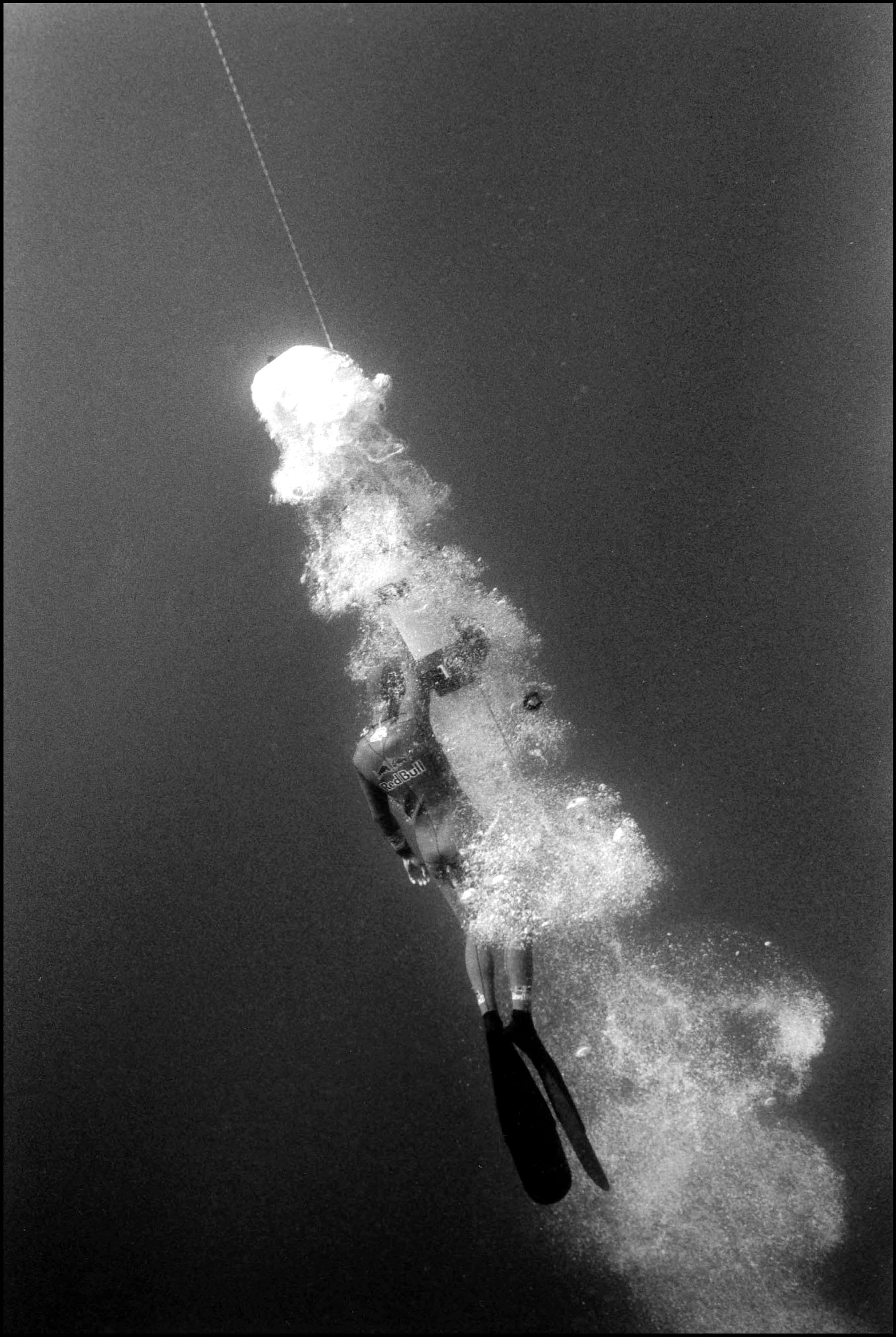

World champion free-diver Pierre Frolla sinks without air to depths unreachable by most scuba divers. One day he nearly didn't make it back to the surface.

This story originally featured in print, in the fall 2015 issue of The Outdoor Journal

Deep down under the sea, so far away from where you live, I have been through the last seconds of my life.

In 2005 or 2006 (oddly I don’t remember), I had the worst accident of my freediving career. After being world champion in variable weight apnea with a dive at 123 metres, where I used a weighted sled for descent and returned to the surface by pulling myself along a line and using my fins, I was training to go deeper.

"No matter what happens to you, you’re stuck underwater. There’s nowhere else to go."

In my sport, risks are quite important. Imagine you’re running a 400-m race. You start way too fast, and after a few hundred meters you’re out of breath and you just can’t go anymore. What do you do? You just stop, walk a bit and slowly catch your breath again. When you’re free diving, no matter what happens to you, you’re stuck underwater. There’s nowhere else to go.

The basis of my sport is quite simple. Going beyond 100 meters is mythic. Only a few hardcore specialists, including the “no limit” guys can go beyond that. Athletes use a weighted sled to dive down and an inflatable bag to return to the surface. This means that the free diver reduces his energy loss to the max, and that’s exactly why he is able to go so deep. The world record is held by Austrian Herbert Nitsch: 249.5 metres on June 6, 2012, in Santorini, Greece. The problem is that at those depths, water pressure is unbelievable! At 100 m, for example, the pressure is about 11 kg per square centimeter of your skin. Consequently, the volume of air inside the human body is pressured and reduced too. Take an empty but sealed plastic bottle: If you get to this kind of depth, it’ll greatly deform. That plastic bottle is a metaphor for your body. This also means that if water manages to seep somewhere inside you through your mouth or nose, it will do so with such force that it’ll destroy everything in its path. Drowning is inevitable, and no Apneist can be saved in such case, even if experienced help quickly intervenes.

At great depths, nitrogen becomes narcotic and leads to what is called nitrogen narcosis. This kind of intoxication from staying in great depths for too long is the same as when you drink too much. In other words, you lose total control of your body and mind, and you become unaware of potential dangers. Acting like that underwater can kill you, as the slightest mistake will have incredible consequences. In my personal training, I mix apnea in variable weight and other constant weight dives, where I dive only with the force of my arms and legs.

Today, my team and I decide to put the weight to 118 m. I know I can go down 115 m, but we want to push a little, as it’s part of training. Once down, I’ll have no choice but to go back on my own. I also know there will be a small parachute and an oxygen tank hooked to the sled, but neither will be for me. The bottle empties very slowly and inflates the balloon. Both serve only to return equipment back to the surface. It’s easier for us to work like that rather than starting a counterweight system.

If I want to live, I have only four seconds to start my ascent. But I am stunned and unable to move. I think about my team: What will they do when they go down to find me, lifeless and filled with water?

"I feel my legs sinking knee-deep in a soft, thick and viscous material."

I begin my descent. I pass my midterm diver. Very soon, it gets dark. I do not have glasses because they would serve me for nothing in this environment. So I stand, with my eyes closed. I’m relaxed and sinking slowly in the water like I’m used to. I feel the pressure now, but I also suddenly feel the sledge slowing. Then it stops, softly. Usually it stops dead. When I realize that something is wrong, I feel my legs sinking knee-deep in a soft, thick and viscous material. It is almost as if moving sands are closing in on me at 112 meters below the surface. It is actually a mixture of clay and silt, a mound a few meters higher than the sonar onboard the boat. It wasn’t identified even though it stood in the stack axis of the descent of my sledge. It’s nobody’s fault; sonar is not so precise.

In no time, I understand what’s happening to me. I’m stuck. I cannot get my feet outside the box, and I know there’s no exit door. I simply do not have enough oxygen to both work my way out of this with strength and go up as I have expected, swimming, with my hands and fins. If I want to live, I have only four seconds to start my ascent. But I am stopped, stunned and unable to move. I think about my team: What will they do when they go down to find me, lifeless and filled with water? I’m dying; that’s it. Today is the day. In 15 seconds, I will have consumed all the remaining air I was keeping for my ascent. I am also a few seconds away from being caught by nitrogen narcosis. I will go crazy right before dying.

"Did I become a vegetable?"

Suddenly, I have an idea. The parachute. Yes! I trigger the opening of the small air valve, which then rushes into the parachute. It’s working but it’s slow and long. So I wait, very still, with my eyes closed. I have no other choice. I try to relax. Everything at 112 m is multiplied by 10. One consumed oxygen molecule at the surface is equal to 10 or 12 molecules consumed at that kind of depth. One second is equivalent to 10 seconds. Time and life are both very cruel at the bottom of an ocean. I am now barely conscious. Finally, I remember feeling the chute tearing me away from my trap like a champagne cork. The ascent back to the surface, back to life, is way too long. When I reach the surface, I have strangely not entirely lost consciousness, but my body no longer responds to my brain. Did I become a vegetable? My team, frightened, retrieves and saves me. If I had not been so well-trained, I would not have survived this scary adventure. Instead of the planned 2 minutes and 40 seconds that I went down under water for, I stayed 3 minutes and 50 seconds. In the boat, I gradually recover and quickly regain all my abilities.

A few years later, I’m on a movie set doing 60-m free diving over and over all day long, and an air bubble is created in my brain on one of these repetitive dives. But instead of being redirected into my lungs, it remains stuck in my head. When ascending, inevitably, this tiny compressed air bubble suddenly decompresses and its size gets multiplied by six. I immediately lose consciousness. Later, I wake up in a hyperbaric chamber. I stay there for eight and a half hours. But when I wake up in that box, I cannot feel my body. I’m unable to move. For hours, I do not know if I will stay quadriplegic or not. This awakening in the box is one of my worst-ever memories of free diving. I do not understand what is happening to me. It takes me 30 minutes to remember that I was free diving and to deduce that I certainly had a bad accident.

Apnea is an extreme sport. I'll remember it always. Yesterday I dived to 113 meters. I’ll do it again tomorrow.

Photos by Franck Seguin

Comments ()