A Sailing Odyssey in the Solomon Islands

Adventures on the Anna Rose, a yacht deep in the Solomon Islands. Growing up on water and finally making it to one of the last truly remote and epic places to sail.1300 hours. 16° 42’ 07” s 167° 24’ 58” E

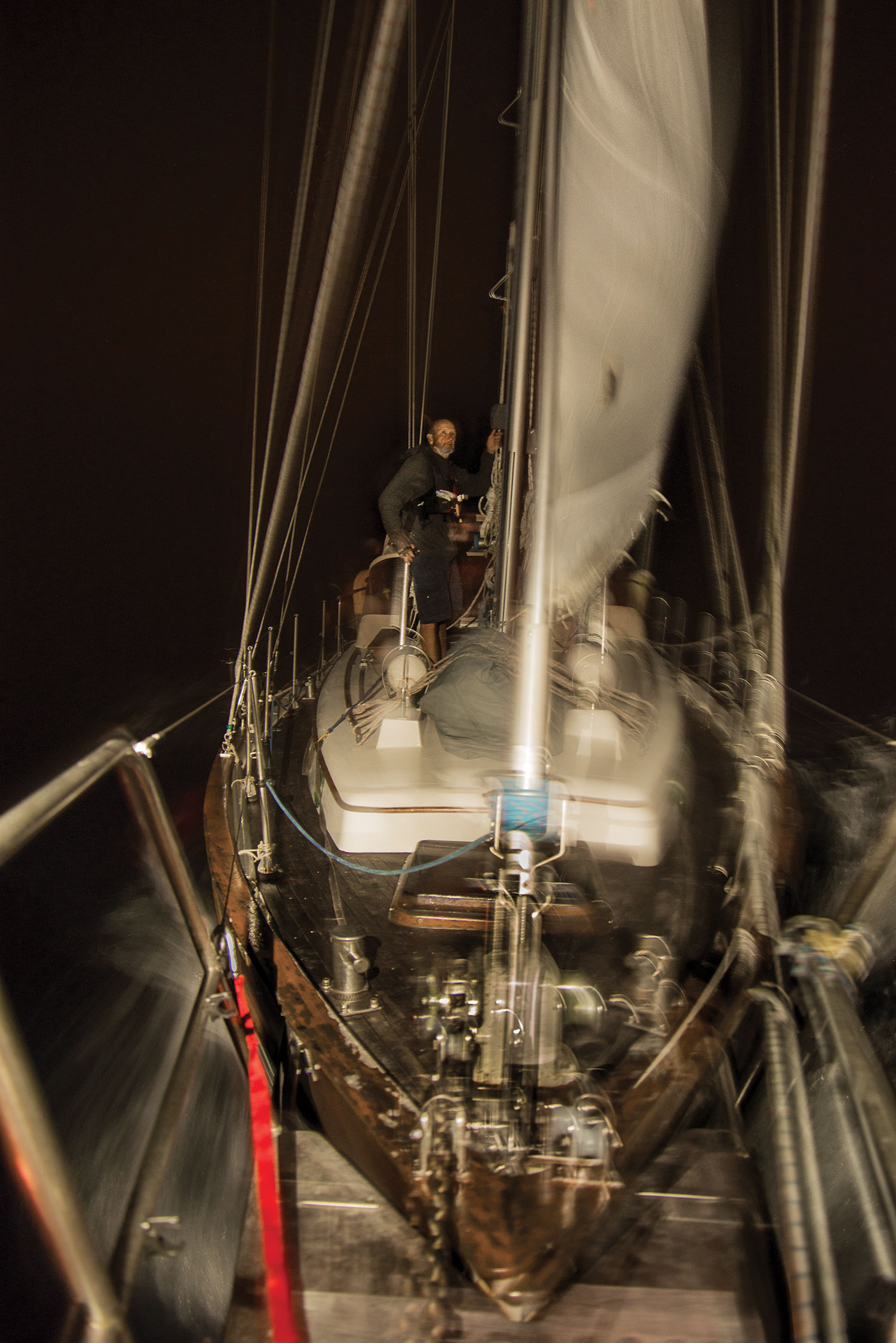

The wind started to howl as we rounded the southern tip of the island of Maleluka, deep in the heart of the South Pacific. We were sailing from the Temotu Province of the Solomon Islands to Port Vila, the capital of Vanuatu. "We need to reef the main! This is the wind we were waiting for!" Our skipper Chris’s face was split into a huge smile even as he shouted out directions to us. We could barely hear him over the air roaring through the rigging. Lucy and I strapped on our harnesses, clipped in, and slipped out from the cockpit onto the deck. The waves began to tower and break, jostled by the now raging wind. Anna Rose jumped and pitched through the water. As Lucy and I made our way carefully toward the mast, I flashed back to my seven year-old feet on the deck of my family’s first sailboat.

When I was little, my father decided to leave the mountains behind and become a sailor. He bought himself a 7-meter boat in the Virgin Islands and soon our family of three moved on board. Dad slept on deck because the v-berth was so small that his legs hung off the bed. My parents would rouse me out of my bunk to make their morning coffee because my berth doubled as the kitchen. My father learned fast and he learned the hard way. While he figured out which anchors don’t drag, how to read the clouds to predict the weather, and how to survive gargantuan seas in a sailboat the size of a teacup, he taught me to love being on the water. Eventually we worked our way up to a more liveable 12-meter Pearson Invicta. At last, my bunk was no longer part of the galley. At some point along the way, I started to daydream about sailing the legendary seas of the South Pacific. My head danced with visions of ancient Polynesians navigating hundreds of kilometres of open ocean, guided by the stars. I wanted to follow in their wake.

There, on the deck of Anna Rose, it hit me that I was actually being tossed around by those same South Pacific waters of my childhood dreams. The distance I was trying to navigate, from the cockpit to the mast, couldn’t have been more than four meters, but those four meters were like climbing a rock wall with a 5.9 pitch that was alive and trying to throw us off. Our acrobatic skills being put to the test, we released lines and cranked on winches. Bit by bit we managed to put two reefs in the mainsail, reducing its size to better cope with the violent breeze. Chris steered us back on course. Seawater rushed over the edge of the deck as the boat heeled deeply to starboard. With the jib and the main perfectly set, her bow started to slice through the waves. We flew over the indigo deep toward Port Vila.

0500 hours. 16° 45' 0" N, 92° 38' 0" W

I had begun this odyssean journey when I had tumbled out of bed before sunrise one morning and set off from my home in Chiapas, Mexico for Lata, in the Solomon Islands, where the crew of Anna Rose, a 13-meter Young Sun, was waiting for me. I devoured a bag of chile-covered mango in Mexico City, barely made my connection in Los Angeles, briefly escaped from the airport to explore the river in Brisbane, and browsed postcards and sarongs through bleary eyes in Nadi. Finally, after an unplanned week-long delay spent meandering through the smoky backstreets of Honiara, floating across the river on a wooden platform to savour barbecue cooked on steel drums, and searching out precious moments of air-conditioning, I caught a small prop plane which delivered me to a grass runway, cut into the bush on Santa Cruz Island. Minutes later, I was in the dingy and wrapping my luggage in plastic tarps to protect it from waves that would spray over the bow as we zipped across the bay to Anna Rose.

1600 hours. 10° 43' 38” s 165° 4945” E

You will not find glitz, glamour, or even a seaside bar for a sunset piña colada in Temotu. And don’t expect to cross paths with another sailboat; only a handful of yachts venture this far each year. The provincial capital boasts little more than two dirt roads, a petrol station, and a small handful of hole-in-the-wall shops. Luckily, Anna Rose’s hold had been stocked with a treasure trove of dry goods and vacuum-sealed foods in New Zealand before setting sail for the Solomons. But we still made sure to pick up some fresh veggies from the local women who display their goods on the ground under an ancient tree. We bartered with a young fisherman for a fresh tuna from the morning’s catch. We filled water jugs from a crystalline spring-fed pool shaded by lush ferns and carried jug after jug back to the boat to fill the tanks. Finally Anna Rose rode low on her waterline, heavy with topped up tanks and a stocked galley. With red gas cans and blue water bottles secured to the stanchions and lifelines, a plastic kayak hanging from the stern, and the dinghy lashed to the bow, we would leave at dawn.

1400 hours. 11° 25’ 35” s 116° 66’ 25” E

I woke with a start when Georgia gently touched my shoulder to let me know it was time for my watch. The red light above the chart table gave an eerie glow to the ship’s cabin. Immediately I was grateful that I had taken a moment to string up a lee-cloth, a long piece of canvas tied from the outer edge of my berth to the inner wall of the cabin, before falling asleep. We were on a port tack. My bed was now at a 20° angle and the lee-cloth was holding the full weight of my body as the boat rhythmically rose and fell, cutting through the waves. After indulging in a full-body stretch that a cat would have envied, I slipped out of my bunk, strapped on my safety harness, grabbed the thermos of chai I had prepared in advance, and then used all four limbs to climb out of the hatch and into the cockpit. I clipped in and turned my attention to Georgia. The tiredness showed on her face as she gave me a quick briefing on our course and how the wind had been over the last few hours. I hurried her off to get some sleep.

The new moon left the sky riddled with stars. Anna Rose danced through the long rolling waves leaving her own stream of constellations as she stirred up the bioluminescent plankton in her wake. The world, with its “shoulds,” “what ifs,” emails, and daily chaos, had dissolved into a velvety blackness illuminated by stars that shone both from above and below. All that remained in the middle was me, in the company of the sea, the sky, the breeze, and the gentle light of the compass leading me through the night.

0800 hours. 11° 38’ 58” s 66° 56’ 18” E

While the rest of us slept, Chris had gingerly picked his way through the reef fringing Vanikoro Island in the dark and dropped the anchor. It had taken us 36 hours to sail here from Lata. The morning greeted us with a deserted bay ringed by mountains and mangroves. I was just about to dive overboard for a morning swim when three girls in a dugout canoe appeared at the mouth of the bay and paddled toward the boat. Chrisma and her cousins had come from the village of Buma to deliver a letter from the chief. “Dear friends,” he had written, “Whether you are friends that are returning or friends we have yet to meet, I would like to welcome you. Please rest, enjoy our beautiful island, and come to visit the village when you would like. If you bring items to trade, there are many things we would like and other items we can offer. Please do not swim in the bay where you are anchored. There are very dangerous salt-water crocodiles there. If you would like to swim, please come enjoy the calm and safe waters next to the village.” It wasn’t until evening that I learned that the crocodiles he mentioned were four to seven meters long.

Buma, like most of the villages in Temotu, is made up of thatch huts scattered along a pristine beach, sheltered by the reef. Women grow vegetables in small gardens scattered among the forested slopes. Men fish the surrounding waters. The village is filled with the bubbling laughter of naked children who do back flips into the water at every chance they get. We visited several villages, drank coconuts in the shade with their elders, played with the babies, and laughed with the kids. But the moment would always come: sticky with seawater from swimming off the beach, bellies full from goodbye feasts, and cheeks aching from laughter, it would be time for us to leave the safety of the harbour behind and head back out into the big blue.

“Ready!” Charlotte yelled out from the anchor winch on the bow. The engine changed pitch as Chris slid it into gear to come up on the anchor. I was down below and slick with sweat, guiding a hundred meters of anchor chain, still a little mucky from the ocean floor, into the hold. The hull gently lurched as the ship became free. I could hear the water start to move against the hull. Having stowed the final links, I climbed back out into the sunlight. Chris steered the boat into the wind as the whole team cranked on lines and hoisted the mainsail and then the jib. Chris cut the engine when the sails caught the wind. Water started to spray over the bow, leaving us encrusted with salt and glistening in the sun as we waved goodbye to the villagers who gave us a send-off from the shore.

1000 hours. 10° 13’ 14” s 166° 16’ 31” E

Between Vanikoro, Utupua, the Reef islands, and Santa Cruz, we had visited nine villages in total and on each crossing enjoyed easy and sun-drenched sails. We had sipped on coconuts as we passed verdant islands that rose from deep blue rolling waters. We had waved back to the silhouettes that waved to us from between the grass huts and coconut trees that were perched above the white sand beaches. And finally the time came to leave the Solomon Islands behind and steer our course for Vanuatu. With the sails trimmed and Chris at the helm, we flew over vibrant coral heads, schools of parrotfish, and the occasional giant sting ray, as we headed for the deeper waters beyond the reef. The blazing blue sky was punctuated with a thunderstorm that flirted with us from a distance. Poised on the bow and gazing at the world below, just as I had as a little girl on my dad’s boat, I thought about how my dream had finally come true. But then I had to laugh at myself. Instead of feeling satiated and ready to cross ‘sailing the South Pacific’ off my bucket list, I just wanted more. I wanted endless open horizons, the constant adrenaline rush of gambling with unpredictable seas, and, night after night, to be embraced by the sea and the stars.

Here are some sailing tips & tricks I've learned along the way:

» Your climbing skills may be put to the test. You might want to practice them before setting sail. When the waves kick up, you won’t only need your manoeuvres while hoisting sails and hauling on lines but while you cook, eat, and enjoy a sunset beer. A 5.11 may look a little easier afterward.

» Use a preventer to tie the mainsail over anytime the wind is behind the beam of the boat. If the wind surprises you without one (sending the boom and thousands of kilos of pressure with it), at best, you’ll give your rigging a thorough bashing. But one line could save a crew member from a pounding headache or worse.

» Check in with the local village before you swim. There may be saltwater crocodiles up to seven meters long. No joke.

» Charts and your GPS can be wrong, especially in the remote areas we were exploring. A good set of eyes and polarized sunglasses are key.

» Everything in the galley is part of the engineering department and is likely to disappear at any moment. It will come back covered in grease and probably a little bent.

» Cook amazing meals. Dried rations don't have to be boring. Stock the boat with spices, yogurt packets, vacuum-sealed grains, nuts, beans, dried fruit, dehydrated milk, smoked meats, and a good cook book.

» Bring silicone earplugs. People will snore even if they swear they don't.

» The recommended anchor is never big enough. Always get a heavier anchor than they suggest. Or be the boat that drags and crashes into the other boats in the harbour.

» Bring spares. Fail-proof means nothing on a boat.

» If you can undo it, it will come undone. Don't get lazy about regularly checking everything.

» Before adding a reef to your main, you can release the boom vang. Wind will pour out of the upper part of the sail, reducing your wind power by about a third.

» Use oil, not winch grease, on the cotter pins inside your winches. Grease + salt = a suddenly frozen winch and thousands of kilos of pressure transferred to your wrist.

» On a clear night, take the 2-6am watch with a thermos of masala chai. Indulge in the childlike wonder of the bioluminescence stirred up by the wake reflecting the stars above.

» Bring a kayak and ask the locals to show you their favourite places to "surf " in their dugout canoes. If you get yourself into a surf competition in the Solomon Islands, know ahead of time that the local competition will win.

» Sailing is 20% climbing, 20% yoga, and 20% mental agility. The rest is a combination of brute strength and how you get on with the weather gods.Nautical Term Cheat Sheet:

Beam: The widest point of a boat’s hull.

Berth: A bed on a boat.

Boom: A horizontal pole or spar that runs from the mast toward the stern. The bottom edge of a sail, usually the mainsail, is attached to the boom.

Boom vang: A line that runs from the base of the mast to a third of the way out on the boom. When tight, this line pulls down on the boom and helps control the shape of the sail.

Bow: The front, back, right and left sides of a boat have their own names when you’re talking with a sailor. Starboard is the right side, port is the left, the front of the boat is the bow and the back of the boat is the stern.

Cockpit: The area where the tiller or the wheel (that you use to steer the boat) is located.

Cotter pin: A metal pin that can be passed through a hole to mechanically hold two components together.

Galley: The kitchen on a boat.

Heel: The leaning angle of a boat caused by the pressure of the wind in the sails.

Hull: The majority of the boat including the bottom, sides, and deck.

Jib: A triangular sail that is attached at the bow of the boat.

Line: Any rope used on a boat.

Mast: A tall pole or spar that rises vertically from the deck of the ship and supports rigging and sails, including the mainsail.

Mainsail: Usually the largest sail on a boat and is almost always connected to the mast and the boom.

Preventer: A line secured to the boom that prevents the boom from unexpectedly swinging to the other side of the boat.

Reef: To reduce the area of the sail exposed to the wind by rolling or tying down the bottom portion of the sail.

Rigging: The system of ropes and wires that supports the mast and sails.

Watch: On overnight crossings, the crew takes turns to watch over the boat while everyone else rests. Your “watch” is when it’s your turn.

Stanchion: Supporting posts that lifelines are connected to along the edges of the deck.

Winch: A device that gives mechanical advantage for hauling on lines that are under tension.

V-berth: The berth or bed that is located in the bow of the boat and, as a result, has a “v” shape.

This story featured in the Spring/Summer Issue of The Outdoor Journal print magazine.

All images courtesy of Britt Basel.

Comments ()