India’s Tiger Census sets a world record ahead of International Tiger’s Day 2020

India executes the largest camera trap survey in the world and doubles its tiger population 4 years before the global target.

‘The Status of Tigers, Co-Predators and Prey in India, 2018’ summary report published by the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) and Wildlife Institute of India (WII) based on the fourth cycle of the National Tiger Census in 2018 has set a Guinness World Record as the Largest Camera Trap Wildlife Survey in the World.

India is home to about 75 percent of the total wild tiger population in the world. These stately creatures have lost about 90 percent of its original home range in Asia over the last 100 years and are now confined to India, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Indonesia, Thailand, China and Russia.

Julian Matthews, founder and chairman of TOFTigers says, “India and Nepal have been successful at saving tigers, because they not only have had a sharp focus and some budget/political will in achieving this – but the one thing they lacked before 2004 was a ‘nature based economy’ that was dependent on viewing wildlife in its natural habitat.”

He is a strong advocate of “tigernomics” or nature based economies that support local communities that are non extractive and value living wildlife. According to him, it is in such areas where the forest department has been the most successful. Julian found TOFTigers in response to the declining tiger population in Asia, “Nobody saves things they do not care about or cannot experience after all.” he explains.

Starting 2006, India advanced from the inefficient pugmark method of estimating tiger numbers (where each tiger’s pug-mark which are unique just like human fingerprints are recorded) to using a more well established method of camera trapping and DNA analysis for estimating tiger numbers.

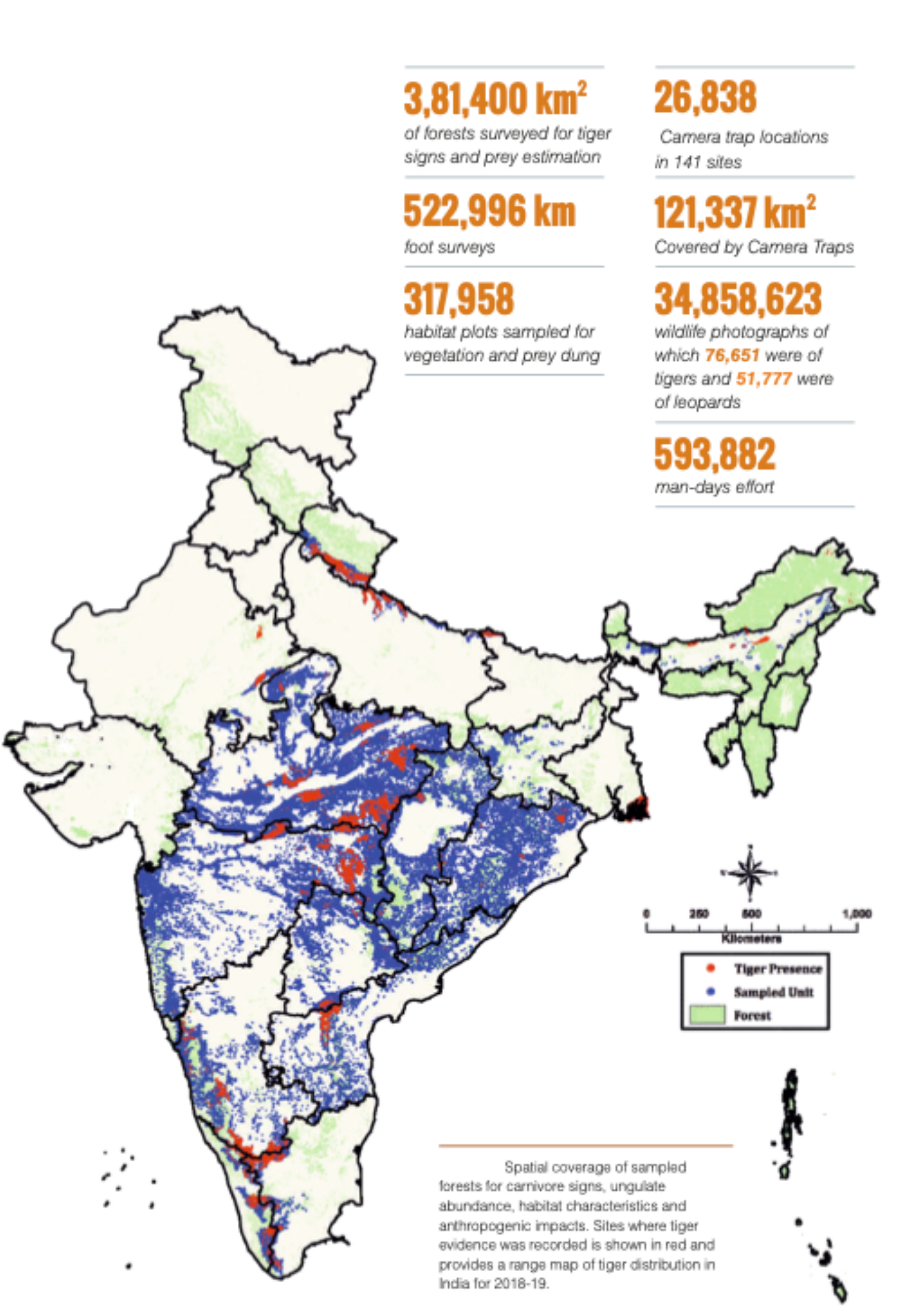

The National Tiger Census of 2018 estimates that India has 2,967 wild tigers, out of which 2,461 individual tigers (83% of the total) have been photographed by the camera traps. The survey was carried out in an effective area of 121,337 square kilometres (46,848 square miles) of the country’s landscape. The tiger population has shown an approximate growth by one-third from the last census in 2014 (from 2,226 in 2014 to 2,927 in 2018 tigers in the wild).

“In the last 14-15 years things have changed a lot. Initially, the number of Tiger Reserves in India was much less and the technology was new. Now we have 50 Tiger Reserves and the new methods have been adopted by the government and people have learnt how to use the equipment. The placement of the camera traps is happening over a large landscape so that is why a larger camera trap survey is possible.” elaborates Dr Samir Kumar Sinha, Head of Conservation, Wildlife Trust of India.

The Global Tiger Forum, an international collaboration of tiger-bearing countries, has set a goal in 2010 of doubling the number of wild tigers by 2022 in each of the tiger countries. India has managed to achieve its target four years earlier. Union Environment Minister of India, Prakash Javadekar took to social media to share the news of these achievements.

https://twitter.com/PrakashJavdekar/status/1281755194020130819

The survey showed an increase in tiger population and non-Indian scientists were invited by the NTCA to review the Census of 2018. The Outdoor Journal shared the experience of Matt Hayward, University of Newcastle and Joseph K. Bump, University of Minnesota who visited the field and peer reviewed the report of this survey.

According to Prerna Singh Bindra, India’s leading wildlife conservationist and author, the estimation exercise is a tremendous effort from the ground level up and the Guinness World Record is well deserved. “It is a matter of pride that Project Tiger (1973) was the biggest conservation initiative of its time and that we lead the world in tiger conservation with a population of 1.3 billion, a fast developing economy and grinding poverty” she says.

Every four years since 2006, a National Tiger Census is conducted by the NTCA and WII in collaboration with the state forest departments and other partners such as WWF to estimate the tiger population in India. Tigers wander about in a large geographical expanse, therefore their habitats have been divided into five major landscapes for the purpose of the survey-Shivalik Gangetic plains, Central India and Eastern Ghats, Western Ghats, North Eastern Hills and Brahmaputra Flood Plains, Sunderbans.

Meeraj Anwar, Researcher at WWF India, based in Haldwani, shares “WWF collaborates with the state governments and assists the state forest departments of Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar for the census, which fall under the Terai arc landscape.”

THE FOUR PHASES OF THE SURVEY

Phase 1 of the survey involves field work to collect ground data.

The smallest administration unit of a forest is called a beat and the forest staff along with volunteers survey each beat over a few days to collect data of carnivore signs, tiger prey abundance, dung counts etc. This information is fed digitally into a specially designed M-STrIPES application with the GPS locations of the observations (In areas with limited network, GPS locations with the observations are noted on paper and entered digitally later). Volunteers are welcome to join these Phase 1 surveys. The foot surveys during the 2018 census survey covered 522,996 km (324,975 mi) of trails and sampled 317,958 habitat plots for vegetation and prey dung.

Sohel Suterwala, naturalist at Taj Safaris at the time, shares his experiences of volunteering for the Phase 1 survey in February 2018 at Pench National Park, Madhya Pradesh. “We had a mock walk before going to camp. After a briefing by the Field Director, I was taken to a camp inside the core area which was in the non tourist section of the National Park.”

“We stayed in an old building on top of a hillock by the flowing Pench river without any electricity or a toilet. There was a solar charger available but it was very slow. We used to even have a bath in the open” he says without any hint of complaint. Over his three days at camp, Sohel accompanied the forest staff daily on a 5 km trail in the beat with a GPS coordinator, a compass and a rangefinder to note down observations. “We actually heard a tiger roar during one of our survey walks” he exclaims. On asking about volunteering for such surveys, he says, “The volunteering process is open to everyone. I think the aim of having volunteers is to be able to have people observe the exercise.”

All the data that is collected during Phase 1 is analysed during Phase 2 to model the tiger occupancy within the habitat with the environment’s characteristics and human impacts.

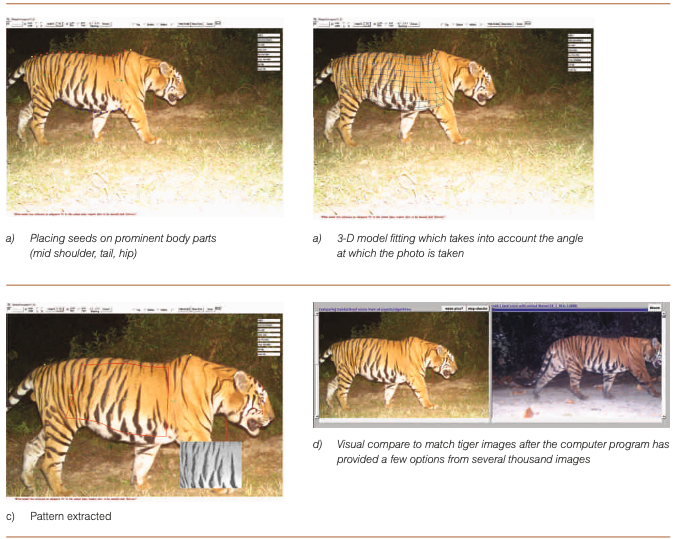

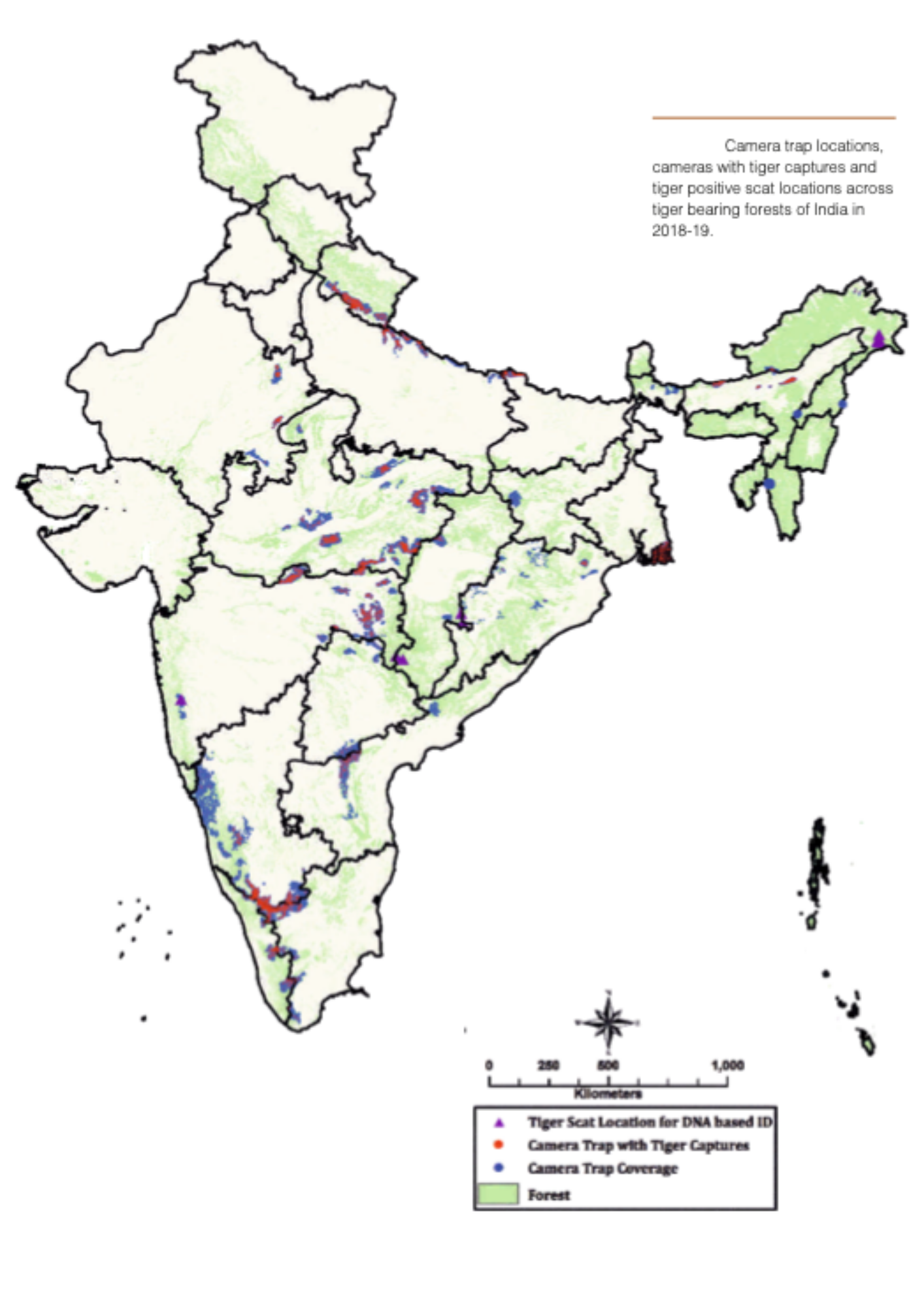

After that, Phase 3 commences and camera traps are placed strategically in the sampling area to maximize the possibility of photo capturing tigers and leopards. The cameras are put in pairs to capture both sides of the carnivore each of which have a unique pattern of stripes or rosettes. According to the report, camera traps were placed at 26,880 locations for mark recapture analysis. Scat samples were collected for genetic sampling simultaneously in areas where camera trapping was not feasible.

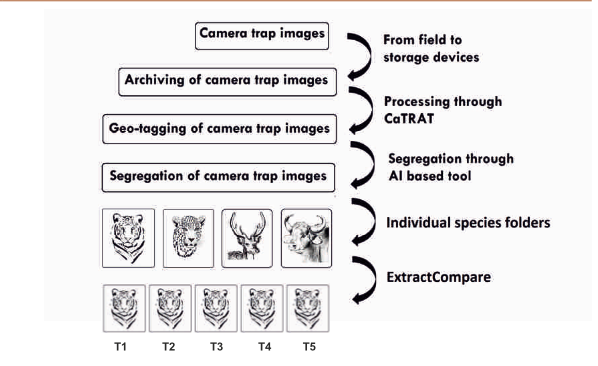

Technology has been well utilised for this survey. An image processing software called CaTRAT was designed to organise and geo-tag the photo-capture. These were further classified using an AI image processing tool into species. Pattern recognition programs called ExtractCompare and HotSpotter were further used to identify individual tigers and leopards, respectively. Using SECR (a likelihood based formula), the camera trap captures and ground survey data were used to estimate the tiger and leopard abundance in each landscape.

In total, the camera traps captured 34,858,623 photographs of wildlife. The total number of individual tigers camera trapped are 2,461 and it has been estimated that the total tiger population of India as of 2018-19 is 2,967 which proves that the wild tiger population has increased.

An investigation by The Indian Express on the Tiger Census of 2014 questioned the tiger numbers estimated by the authorities. The official photos from the camera traps were analysed and they concluded that one in seven could just be a paper tiger. However, the tiger estimate of 2018 has higher credibility since 80 percent of the tigers have been recorded individually on the camera traps.

The survey also finds that while established and secure tiger populations in some parts of India have increased, the small, isolated populations and those along corridors between established populations have gone extinct. This highlights the importance of tiger corridors and avoiding fragmentation of tiger habitats.

"There is no time for complacency as the tiger continues to be gravely threatened with destruction and fragmentation of tiger habitats. Also, with wildlife crime on the rise, we need to empower concerned enforcement agencies and forest staff on the frontlines of wildlife protection.” says Bindra.

TIGER TOURISM IN INDIA

The tourism industry of India employs 15 million people but how does it impact tiger conservation?

While discussing Tiger Tourism in India, Mr Mandip Singh Soin, Founding President of the Responsible Tourism Society of India, says, “Tourism, when done in a proper manner can be advantageous. Locals can benefit from it and the tourists act like the eyes and ears of the forest. The stakeholders of conservation multiply when you get locals involved. ” He provides an example of snow leopard tourism in northern India where locals have turned their homes into Guest Houses which benefits the community and the wildlife.

However, he adds, “Many times tourism is not being done in a sustainable manner, as can be seen with too many lodges in Corbett.” He suggests ideas like using GPS to avoid overcrowding during safaris and giving a push to local handicraft for sustainable tourism. “The ultimate goal is to support conservation.”

Adding to it, Julian Matthews’s TOFTiger which certifies nature friendly places to stay in the subcontinent says,“I take my hat off to the Indian Government. I don’t think they could have done it without the economics of tourism because tourism does more than what you think.” He explains how the local economy benefits from tourism and how the tourists become educators to their friends and family based on what they experience. He adds that the reserves may even get international publicity when they do well. “There are many disadvantages too but it (tourism) is a very powerful tool for the forest economy.” says Julian.

THE FUTURE - Where do we go from here?

The survey of 2018-19 may have found that the total number of wild tigers have increased in India but has it occurred in a holistic manner? The tigers need space not the numbers to survive and the more number of tigers we have in smaller spaces, the more the tiger is going to get into conflict.

"Counting tigers only provides us with an indication of the presence or absence of tigers. It should not be posited as a measure of long term success. That success should be measured by the quality and extent of the tigers' habitat and its continuity with other tiger habitats. Today we have lost possibly around 60 per cent of all the forests in which tiger pugmarks could have been seen in 1973 when Project Tiger was born. How can we ever hope the species will survive long into the future if we take pride in over-populating smaller and smaller parcels of wild lands? Having said that the camera trapping exercise is a great monitoring tool for management,” says Mr Bittu Sahgal, Editor, Sanctuary Asia magazine and Founder of the Sanctuary Nature Foundation. He goes on to say that he would be more excited to have a Guinness World Record for using nature-based solutions to rewild the largest parcels of tigerland that were degraded by humans. Or perhaps for the 'Largest Number of People who join the mission to Save the Tiger'.

"Sanctuary’s one-million-strong Kids for Tigers Programme, which was launched in 1999 is trying not just to leave a better planet for our children, but better children for our planet. After all, our children have the greatest legitimacy to demand a better future for themselves and the tiger is basically a metaphor for all of nature, which alone can guarantee humans a better, safer future," explains Mr Sahgal.

“Predators have been almost wiped off in most of the western world. So India's tiger conservation achievements are all the more remarkable. It is strong political will and the tolerance of people living close to wildlife that has saved our tigers. However, political will is waning. If tigers are to survive in the long term or the future, tiger habitats must be conserved and be ‘no-go’ areas.” adds Prerna.

Julian Mathews from TOFTigers says “I think the future of India tigers is 10 times better than the rest of Asia.India will save its tigers. They will probably be in small pockets and there might be some manipulations. But they will survive. And there will be money to save them and that money will come from nature tourism.” but when Mr Mandip Singh Soin touches upon the various development projects in the country’s natural landscape (195 projects have been cleared during the COVID-19 pandemic alone) he wonders, “Are we selling our soul to development?”

Highways and railways are cutting across the forest landscape, dams are being planned in fragile ecosystems, tiger poaching is being reported even during COVID-19. “The most prominent kind of developmental activities in our forests are linear infrastructures-roads, highways, railways. We need mitigation measures and exclusive passages that are ‘eco-sensitive’ zones. We cannot stop each project but we are quite hopeful. The possibility of tigers surviving is high if we manage the tiger corridors.” says Meeraj Anwar, Researcher at WWF India.

The legal framework in India is being diluted with proposals like the EIA 2020 that will give clearances to projects more easily without determining its impact on the environment. Furthermore, institutes such as the Wildlife Institute of India which monitor the forests and landscapes have also weakened. Making wildlife a priority and planning growth sustainably is the only hopeful way forward. Protecting the tiger is used as a metaphor to protect the entire ecosystem by many conservationists as it is a keystone species. Forests ensure food and water security among other necessities and no economy can go on without it for too long. It has also been estimated that three-quarters of new and emerging infectious diseases in humans originate in wildlife due to our encroachment, such as COVID-19, SARS and Ebola. So we need to decide where we are headed now?

Cover Photo source Prakash Javadekar's tweet dated 11 July 2020

Comments ()