World's Hardest Dry-Tooling Route Established in Canada

Canadian Gordon McArthur is one of the best dry-toolers in the world, scaling steep rock walls with just his ice tools and crampons. For the past three years he has been working on what would be the hardest drytooling climb ever if he could somehow finish it. Last week, he finally did.

After climbing upside down for over 45 minutes, Canadian Gordon ‘Gord’ McArthur had three moves left. He had already powered his way 75 meters out the underbelly of the cave, and now, after dozens upon dozens of tries and countless hours of work over three years, he could almost taste success. If he could will himself up those last few meters, the climb, Storm Giant, would be the hardest dry-tooling line in the world.

“I said in my head, ‘If I fall here, I’m never coming back.’ I knew I’d never be able to recover mentally and emotionally to get back on from the bottom,” McArthur says.

Just three more moves...

Dry-tooling is something of an oddity in the climbing world: it consists of climbing purely on rock using ice tools and specialized crampons called fruit boots. The discipline takes the skills pioneered by American alpinist Jeff Lowe to climb mixed ice and rock lines, but removes the ice component entirely. The result is a climbing style that allows for the most gymnastic and futuristic lines imaginable.

Whereas mixed climbs (lines that includes both rock and ice sections) receive an M grade, dry-tooling routes get a D grade. The levels of mixed climbing and dry-tooling have advanced rapidly since Jeff Lowe established Octopussy, the first M8, in 1994. These days there are fantastically difficult climbs lines like The Mustang P-51 (M14-), Saphira (M15-) and Iron Man (D14+).

In 2016, British alpinist Tom Ballard made the first ascent of the 50-meter A Line Above the Sky in the Dolomites, Italy, and graded it D15―the first dry-tooling route of the grade.

In the downtime between Ice Climbing World Cup events each year in Europe, Gord McArthur, 37, goes to the mountains and tries the toughest routes around: “I’ve had the opportunity to climb on almost all of the hardest lines, actually”―including Ballard’s testpiece―“and I’ve sent some of them. It’s good to have that comparison for opening new routes,” McArthur says.

So with those reference points in mind, when he first discovered, equipped and started trying Storm Giant near his home three years ago, he was fairly certain that―if he could climb it―it would be the hardest dry-tooling climb ever completed.

A friend was the first to show McArthur the cave, only about an hour from his house in British Columbia, Canada. After scoping it out, he started bolting the Storm Giant project right way. “It took me a year and a half to bolt the route because of the sheer length and logistics of it, but also because the energy and the cost―there are over 50 bolts on the route,” he says.

“Some bolts would take 45 minutes to get into the wall before you actually felt safe about them. In many instances I’d put in a bolt, I’d start twisting and the rock would just be breaking away.” (Since using ice tools can chip and damage the rock, dry-toolers usually develop cliffs that are deemed too loose and chossy for rock climbers to be interested in.)

But bolting the line was only the beginning. “When you look at the route you think, ‘How can someone climb something that long and that steep?’” McArthur says. “80% of me thought it was impossible.

“But the other 20% kept lingering: What if it was possible?”

He began trying the line with little success. “There was almost no progress. It was really disheartening,” McArthur says.

That continued for, quite literally, years. He tried it again and again each season.

Then, just under two months ago, all of his hard work started paying dividends. There were breakthroughs, new highpoints and bigger links. “It gave new light to hope,” he says. Suddenly, it seemed not just possible, but even probable.

The final hard section of the climb came just a few meters from the end. When he finally reached that point in one continuous climb from the ground, he and his coach realized he was spending too much energy trying to clip the quickdraws in the crux section. McArthur decided he’d just have to skip them if he wanted to send.

He rested for two days and then went for it. He got to the crux, skipped the crucial draw, and climbed through to the final rest before the end.

Then he just had three moves left.

“The last three moves felt like they lasted an eternity, because I didn’t want to screw it up,” McArthur remembers. “You climb 75 meters and you’re exhausted. But all of a sudden I felt like I had superhuman power. There was no way I was letting go at that point.”

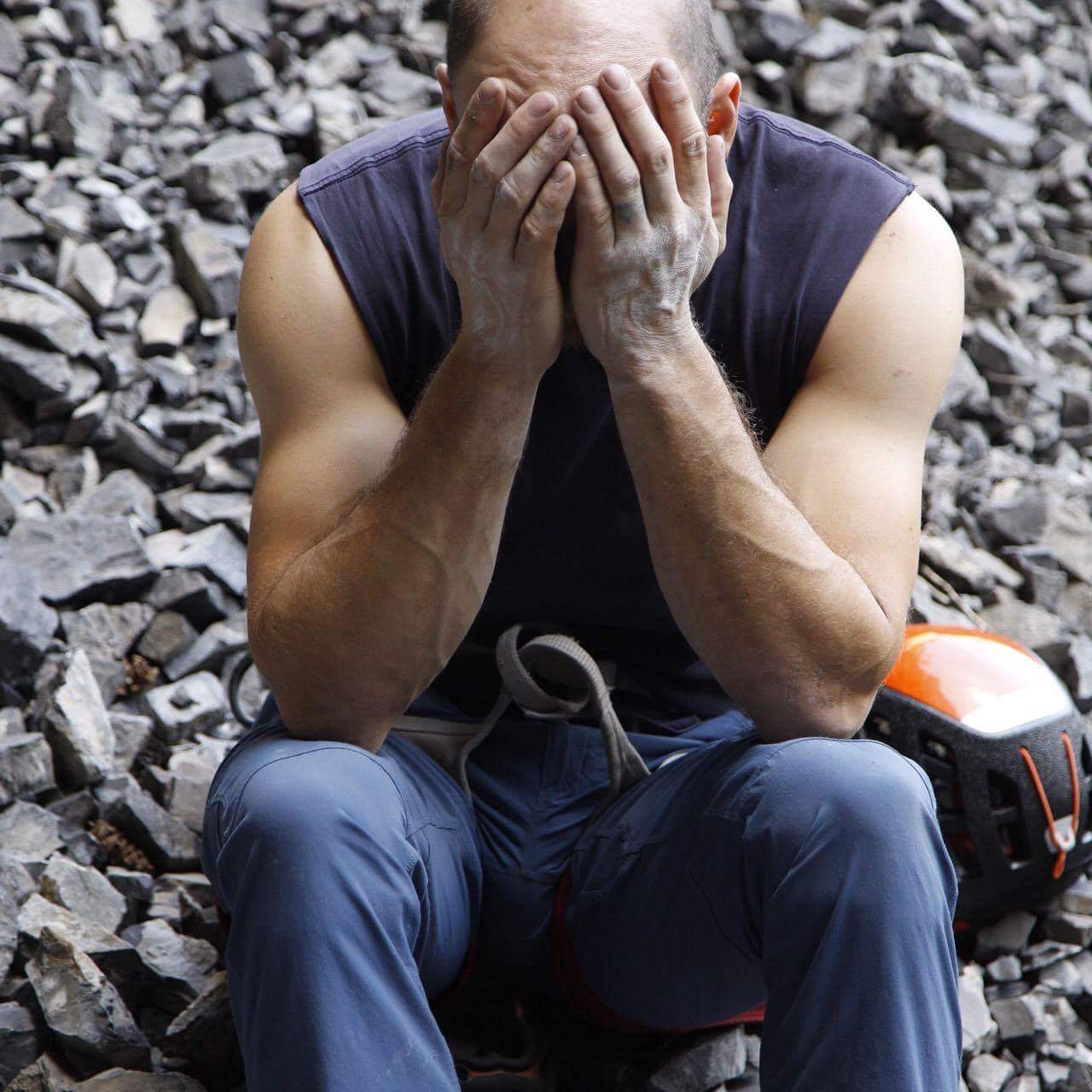

He executed the last moves and clipped the chains. Storm Giant was complete. “I don’t cry ever, but my body just let go emotionally at that point,” he says. “It had felt like an unrealistic goal most of the time. I wouldn’t say it was the impossible, but for me it felt like my impossible, if that makes sense. Clipping the chains, I couldn’t believe that after three years I had finally done it.”

[embed]https://www.instagram.com/p/BX_L6eRgbQ8/?taken-by=gord_mcarthur[/embed]

After reflection and discussion with others familiar with what the project had entailed, McArthur decided on the grade of D16.

“It’ll stand until it doesn’t,” he says. Explaining his reasoning behind the D16 grade, he says, “It’s the longest and hardest route in the world, I’m sure. So since the hardest before that was D15, taking all those factors into account―hardness of the moves and the length―it makes sense to suggest that new grade. You have to brave about it though. It’s scary tossing out a new grade. You’re doing something that no one’s done before, and you’re setting a new bar. There’s always the naysayers doubting you, but you have to just sort of take that and be confident.”

Storm Giant was about far more than the grade for McArthur, though. “It became about me and what I was capable of mentally and physically. How far I could push the edge for myself. Especially the past couple months I totally let go of the grade thing. It was more a personal journey of if I could do this, whether I could overcome what I thought was impossible.”

“It’s still so surreal. I still haven’t recovered from the fact that I actually did it."

Feeling inspired? Go to The Outdoor Voyage and book your next trip.

Comments ()