It’s legal, but that doesn’t make it right. The decimation of Africa’s wildlife to indulge East Asia’s appetite for animal products is escalating. It is unsustainable and must be stopped.

Quite apart from the decimation of illegal poaching, legal export to Asian markets is tearing the wild heart out of Africa. Each year thousands of tons of live animals, bones, skins and meat head East in a plunder with no end in sight. The scale at which Africa’s wildlife is being drained by Eastern market demand is enormous, according to a report by the wildlife monitoring network TRAFFIC released this week.

The focus on wildlife trade from Africa generally centers on the illegal trade and the massive poaching of iconic species such as elephants and rhinos. However, comparatively little attention has been given to legal wildlife trade from the continent.

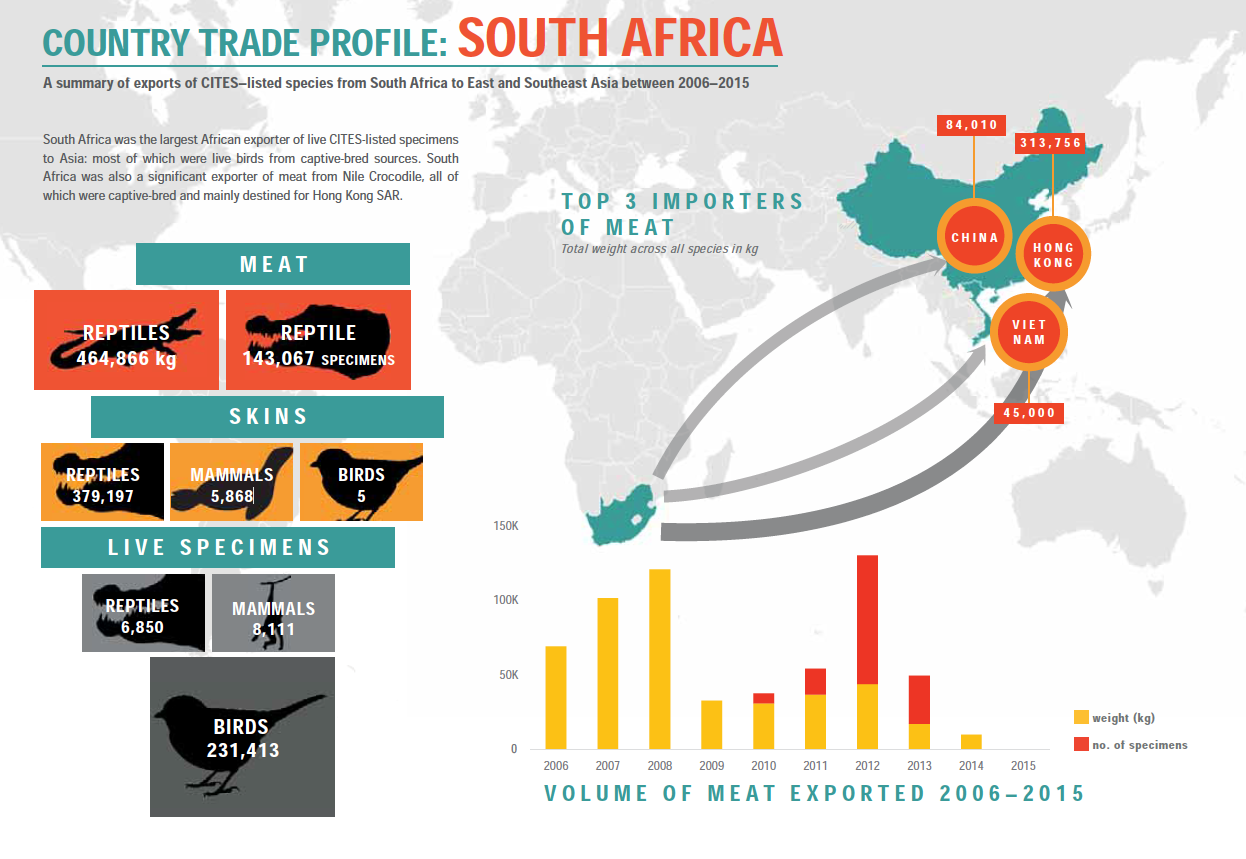

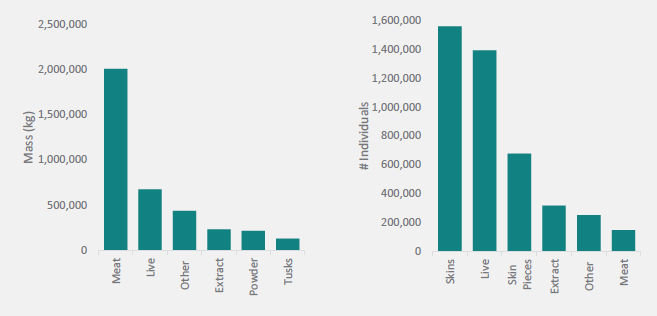

According to TRAFFIC, between 2006 and 2015, almost 1.4-million live animals and plants, 1.5-million skins and two million kilograms of meat from CITES-listed species were legally exported from 41 African countries to 17 countries in East and Southeast Asia.

The report – Eastward Bound – Analysis of CITES-listed flora and fauna export from Africa to East and Southeast Asia – warns that these export volumes are huge and escalating.

South Africa proved to be the largest seller of live birds, mammals and plants. Namibia was, by far, the greatest exporter of mammal skins – mainly those of Cape fur seals – most going to Singapore and Hong Kong. The second most common mammal skin exported was from elephants, with 11,285 sold from Zimbabwe (8,744 ) and South Africa (2,533). The greatest overall number of skins exported, however, were from Nile crocodiles – over 1,4-million.

Over two million kilograms of meat was also exported, most of it being from just three species: Nile crocodile, European eel and Cape fur seal. The largest importer of reptile meat was Hong Kong.

The scale of killing can be gauged by one seemingly bizarre export. In just 10 years, more than 50 tons of hippo teeth were marketed to the East from Uganda and Tanzania.

Live trade was dominated by two species which generally receive little attention: leopard tortoises and ball pythons. Importers of live animals were predominantly Japan, Singapore and Hong Kong. These and mainland China dominated skin imports and Singapore plus the Republic of Korea were the main meat importers.

The most commonly exported birds were African grey parrots, with 40,475 leaving South Africa between 2006 and 2015 and 34,283 from the DRC. The species was uplisted to Appendix 1 (endangered) in 2017, but several parties, including the DRC took out a reservation against the ban.

For some reason, there was a run on Fischer’s lovebird in 2013, with 65,315 heading for Asia. Although the bird is native to Tanzania, all exports were from captive sources in South Africa.

During the 10-year period under review, a major export was also wood, with 10-million square meters – much of it from virgin forest – bound for the East. Most of this was driven by exports of African teak, more than nine million square meters coming from the DRC’s fragile rainforests.

Next Read on The Outdoor Journal: a Psychologist's Understanding of the Mind of a Lion Murderer.

It is likely, according to the report, that these overall export numbers are low in terms of what actually leaves the continent. ‘It is recognised, reads the report, ‘that not all trade reported in the CITES Trade Database was sourced legally. For example, specimens may have been taken which exceeded national harvesting quotas, or taken from the wild and falsely claimed to be captive-bred. ‘It is possible that such specimens make up a significant proportion of total trade reported. Also many species were only recently listed in CITES, so will not appear in this review of trade data for 2006 to 2015 in large amounts or at all.

‘Exports of shark and manta ray products do not feature highly in this analysis. Although many were listed at CoP16 (2013), the listings did not go into effect until September 2014 and therefore Parties will not have reported trade until then.’

Of all of the species listed at CoP17 (2016), including sharks, rays and timber species such as Dalbergia, restrictions did not enter into effect until 2017.

‘It is also useful to compare patterns of legal trade from a country with that of illegal trade,’ says the report. ‘Some countries thought to have a large illegal trade have very small or non-existent legal trade. Others have legal trades that far outweigh the estimated size of the illegal trade.’

As there are only very rough estimates of poached or illegally captured animals and unlicensed timber harvesting, the scale of extraction of Africa’s living products or their derivatives is unmeasurable but undoubtedly enormous.

For more information on promoting sustainable wildlife trade, visit Conservation Action Trust.

Feature Image © Conservation Action Trust

This is an Op/Ed piece. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect an editorial position of The Outdoor Journal.