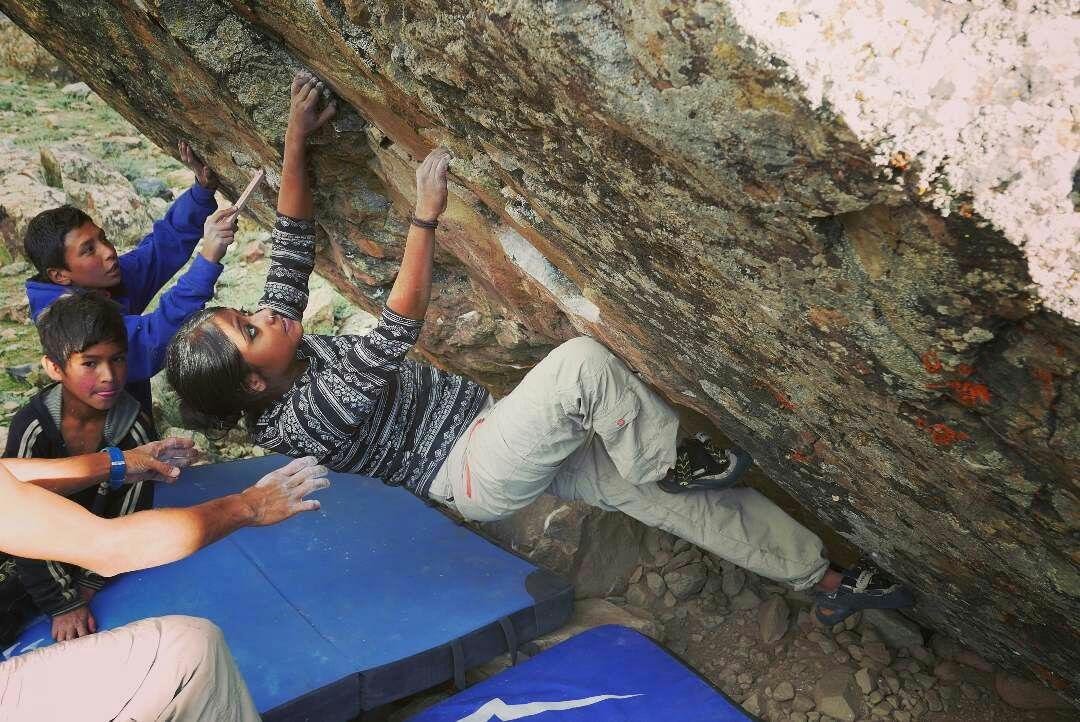

India’s Climbing Scene: Why Aren’t More Women Climbing?

What makes it so difficult for Indian women to take up climbing? A few female climbers offer insight into an entry barrier posed at the intersection of patriarchy and personal safety.

“What do you want to do in there?” we were asked by two policewomen at the entrance to Thurhalli, a bouldering area in Bangalore

“Climbing!”

I vaguely gestured using my hands what ‘climbing’ meant. I was with two friends, Aravind Selvam and Gowri Varanshi.

“Do you know there was a murder just last week?” they asked. I said I didn’t.

“…and you have a girl with you” they continued, looking at Gowri. “It would be different if it was just you men.”

Gowri’s black sleeveless top invited a glance from the policewomen. In one of India’s more bizarre public discourses over the last few decades, a woman’s sleeveless top has been offered as an explanation by various self-righteous entities (including the police) for everything from low academic performance to compromised personal safety.

I tried reassuring them that we will safely climb within eyeshot.

Gowri’s Bangalore climbing guidebook broke some ice, as she used it to chat with them about the sport. They opened up and even ended up suggesting some hillocks from their hometowns worth visiting.

Finally feeling at ease, we proceeded to a problem called Dark Cloud.

It’s one thing that the “murder last week…” was used as a deterrent. But, to be honest, the officers’ concerns were legitimate. Outdoor spaces in many parts of India aren’t the idylic safe havens they’re romanticized to be.

How so?

“There are all these loafers…just roaming about…” they explained.

Nearly every Indian woman knows what the policewomen mean. Groups of men who just ‘collect’ at getaway spots, close enough to the city, but far enough for a picnic. What do they do here? Drink, play cards, just let loose. Nothing wrong, in itself. But it gets uncomfortable when the staring and probing begins, which it often does when a female is around. These groups of men are just that, men. There are no women or children; which may itself be reflective of a larger issue.

Gowri has had firsthand experience with this. “A group of us girls and one guy wanted to go swimming in the Sanapur Reservoir in Hampi. 13 to 14 men just walked up from the main road because they saw us, I guess. They weren’t doing anything actively aggressive, but their body language made us all uncomfortable. They found these vantage points, spread out and then just stood there – arms folded, straight-faced and staring.” The group of swimmers were mostly Indian women who wouldn’t necessarily show the amount of skin a foreign tourist would. Not because it’s morally wrong but from years of accumulated discomfort from reactions like these.

This is a complex social problem in India – the systemic separation of genders which results in uncomfortable adult interactions. Ultimately, this culminates in the stability of gender roles which leave women with less agency - whether this involves an implicit expectation to make tea or choices in career, life partner and such.

At the very least, it creates permanent ‘walls’. The radar that women must ALWAYS have on. Just going into public spaces entails having to deal with staring, kissing sounds, ‘accidental’ touching, and ‘playful’ following. Gowri characterizes this as “usual”. Climbing alone, as I have, or even with a small group of girls is something she will never do in Thurhalli, her home crag, or almost anywhere in India. And that’s not even the start of my male privilege.

Let me be blunt. I’ve never ever had to fear getting raped, when outdoors. I’m writing this not to ‘be a voice’ for the community, but from an attempt to understand that the female climbing experience is extremely different and riddled with broader socio-cultural factors I may never have to deal with because of my gender. As a man, I feel it’s a conversation worth having, NOT leading. Can my intent devolve into patronizing banter? Definitely. I must consciously strive to work against this.

As the sport grows, broader social patterns (class preferences, for one) will start becoming more visible. As of now, Gowri says she's never been sexually harassed by anyone from the outdoor community. A stark contrast to her everyday life.

Prerna Dangi feels a bit differently. She has no hesitation in climbing alone or with a smaller group of women. What she deeply dislikes is the unsolicited chatter, usually, when traveling, that crosses personal boundaries. A subject that keeps coming up is her build. She describes reactions to her hauling a climbing rack, “Someone is always shocked at a girl carrying so much weight because ‘she can’t be that strong!'” The interactions then range from questions about whether she’s a ‘trainer’, to patronizing offers to help.

“just ignore it…” or "what to do…”

Prerna feels safe within the outdoor community. “There is a tacit understanding I can place on them to be cool…” she says speaking about how sexual safety isn’t on her mind in the outdoors. Interestingly, #SafeOutside, a survey, and initiative examining sexual abuse and sexual harassment in the climbing world (the USA primarily, but other countries have started) - showed that 1 in 2 female climbers and 1 in 6 male climbers experienced sexual abuse or sexual harassment while climbing. India has yet to develop the sample size for a meaningful survey of the kind.

Prerna’s experiences risk being trivialized with reactions like “just ignore it…” or “what to do…” This is where, as a community, we need to be careful. For many women, the fear of not having empathetic listeners could turn them away. This is also a predominant reason abuse victims stay silent. The effort to reward ratio gets too skewed.

Tania Kar knows that feeling. “You have to put in twice the effort of any man to make sure you have an uneventful experience.” Part of that involves quick thinking to minimize damage. “Once, while on a train back from a competition, a man broke into the washroom cubicle, made his way towards me and locked the door from inside. I grabbed my phone and pretended to dial a number. He seemed to measure his odds before saying ‘Chal Jaaney Dia’ (I’ll let you go this time), and exiting the cubicle.” Somewhere down the line, it no longer feels worth it. Tania was telling me how she broke down while returning from buying cigarettes after a long climbing day in Leh, when she was catcalled at night. A very drunk man asked if she would “…go with him”.

Chances are, many who read this may ask “Cigarettes? At night? Why would she do that?”

But are these the right questions to be asking? Should we be putting the blame on the women for going out at night? Or is the problem actually in the fact that it is dangerous for women to go out at night alone?

An older climber fondled her breasts.

“A system that has painstakingly made sure women remained dependent (on men) isn’t going to change overnight,” Tania says, alluding to her frustration about requiring male company to go places. Nonetheless, she thinks it necessary to include men in conversations about sexual safety and the outdoors. Though at times patience-testing, experiences with her male friends have been largely positive. “There’s a fine line between you “could” do that and you “should” do that. Often men fail to notice this".

This role of men as protectors and ‘big brothers’ is slippery. In Kannada, older climbers are typically referred to as ‘Anna’ and ‘Akka’, meaning elder brother and sister. This can come with a forced subtext that they are incapable of having bad intentions. Forced trust in one’s elders.

One female climber, who requested anonymity, speaks about how an older climber fondled her breasts on a bus ride back from a training camp when she fell asleep on his shoulder. She had to ease herself out of the situation tactically, just pretend that she shifted sleeping positions and move on as nothing happened.

The unintentionally patronizing man is another topic unto itself, ultimately coming from the same place – patriarchal messaging. It begins from the pinks and blues in nursing rooms. Barbies and action toys. The separate lines in schools. Years of converting natural differences into ‘roles’. Climbing, special as we think it is, does not exist in a vacuum.

When the subject of low female participation comes up, it helps to think of public spaces in general. How many women in India get the opportunity to just have tea and stand around as they please? Or go out at night without a male ‘protector’?

If we begin there, we could start training as allies.

Cover photo: Gowri Varanshi bouldering in Hampi. Photo by Paul Rosolie.

Comments ()