Charge Hard, Stay Smart: Guru, Fritz Sperry, on Safety in Avy-Prone Backcountry.

Local guidebook author Fritz Sperry knows the Colorado backcountry as well as anybody. The Outdoor Journal were invited on an outing, so Kela Fetters grabbed her Skis and started trekking.

It’s early March, and there are signs that Old Man Winter’s stranglehold on the Tenmile Range is giving. The first evidence is auditory; birdsong punctuates the otherwise mute atmosphere of Mt. Victoria’s evergreens. It’s snowing, but the temperature hovers just below freezing and the resulting flakes are quick to liquesce. Rainbow Creek, invisible but animated, gurgles under several feet of snowpack. Fritz Sperry, doyen of Colorado’s Front Range backcountry skiing guidebooks, is deep in research—waist-deep, in fact, given last night’s snowstorm.

In guidebook parlance, “research” is synonymous with “training”. Sperry uses his go-to powder stache in the Tenmile Range as the setting for notching some spectacular vertical. It will all pay off come springtime when he will redeem his accumulated fitness on big lines around the state. Everybody wins when Sperry skies a new descent; the endeavor will likely end up in the next edition of his backcountry guidebook, along with critical information about access, technicality, and avy potential.

Sperry’s been skinning around the Centennial State for 26 years, but his blunt vernacular betrays his Bronx upbringing. He moved West thirty years ago after cutting his backcountry teeth at Tuckerman Ravine in New Hampshire and answering the siren's call of the Rockies. Sperry began writing his first guidebook in 2001 and has since documented his exploits up and down the Front Range. Expletives aside, he knows snow, especially Summit County snow. As we trek upward, he periodically assesses the snowpack with his poles and hands. He chooses representative slopes and stomps cornices. He notes even slight variance in wind and weather. Rounding an exceptionally spicy kickstep in the skintrack, he pauses and shakes several Sour Patch Kids into his palm. “Want some caaaandy?” he offers mischievously.

Playfulness gleams in his eyes, but vigilance seems to underpin his backcountry ethos. Our outing was a testimony to the centrality of assessing avalanche conditions on the ground. The Colorado Avalanche Information Center (CAIC), a backcountry aficionado's go-to intel site, posted a Level 3 “Considerable” avalanche warning, but Sperry sleuthed signs of solid stability throughout the day. CAIC forecasts alone should not determine route-planning; in-situ observation supplement general predictions. Slopes can slide under any avalanche rating. On our particular outing, stable snowpack conditions made evident that sometimes, you can have your CAIC, and eat it too. "What are the biggest things to watch out for when assessing snowpack stability?" I asked Sperry. He had a veteran's robust answer: "To me, there are two seasons, winter and spring. These aren’t dates on a calendar but a snowpack condition."

"The winter snowpack is a layered cake and slab avalanches may be the result. The elements of a slide are the most important thing to keep in mind when trying to assess the risk: slope steep enough to slide, trigger, slab and weak layer. You need all of these elements for a slide to happen. You can eliminate one and not have any issues. The easiest element to control is the slope angle."

"In spring we deal with melt/freeze snow. This might happen any time of the year but usually, it’s once the sun gets high and the melting and freezing process begins. Corn is the offspring of this process. Wet slides are another child of this. Focusing on timing can help with this situation. I often hear talk of the ‘alpine start’. This is great if you’re planning to ski an east facing line, but a 4am start for a southwest face will only lead to the loss of fillings from the rock-hard ice you’ll be skiing [conveniently, Sperry's guidebooks feature a "sunhit" estimate for users to optimize their line's solar exposure]. Time your line so you’re skiing after the sun has been hitting it for a few hours. If the slope you’re planning on skiing is too soft, back off to less solar aspects. If you penetrate the spring snow to your ankles, it’s time to bail."

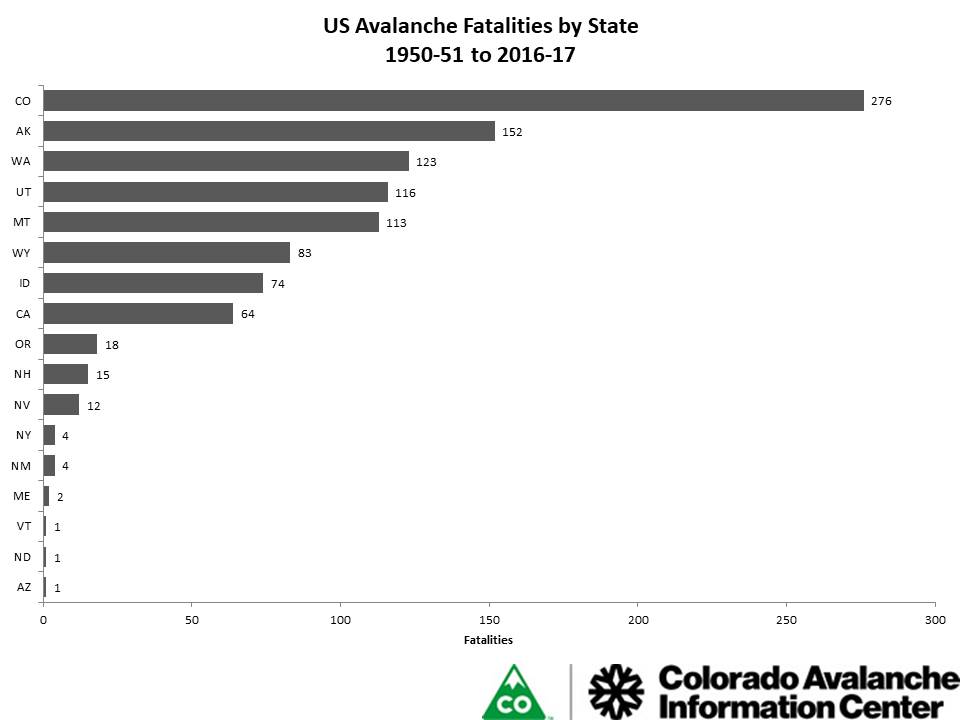

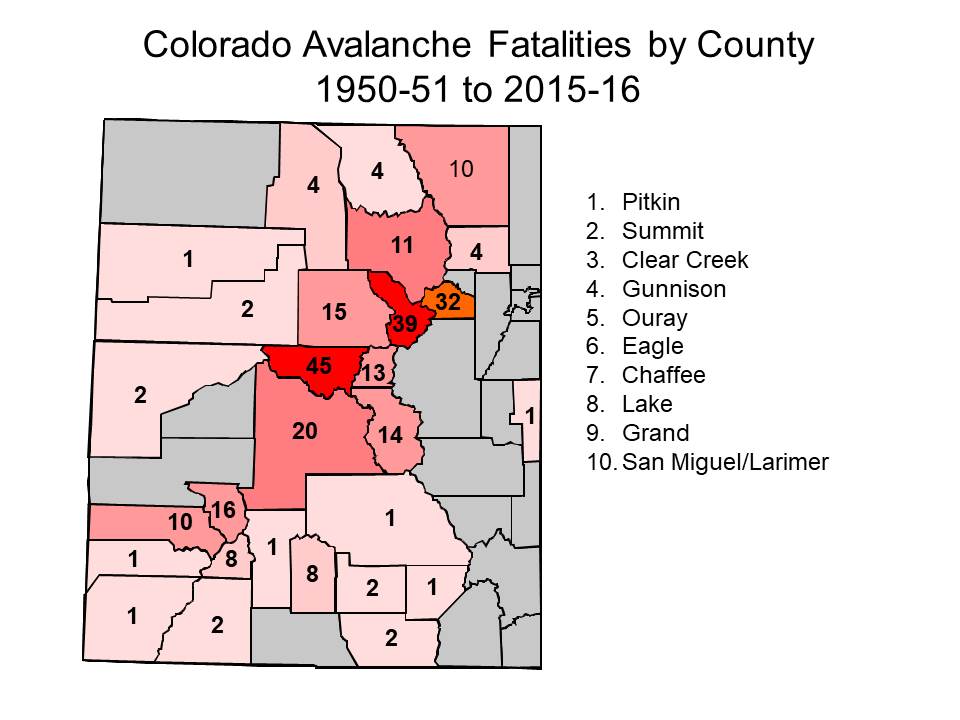

Colorado sees more avalanche deaths than any other state, but backcountry recreation is on the rise.

Backcountry skiing in Colorado is witnessing an enormous surge in popularity. As resorts have become increasingly crowded, lift-accessed terrain gets skied out in a flash. I-70 traffic crawls, parking lots overflow, resort titans Vail and Alterra duke it out for dominance —it’s no wonder that a growing number of skiers have sought solitude out-of-bounds. According to a Snowsports Industries of America report, sales of backcountry gear like alpine touring (AT) bindings rose 84% from 2017 to 2018. Forest Service research uncovered a 15% increase in participation numbers for backcountry skiing and splitboarding between the 2015/2016 and 2017/2018 seasons. The same study forecasted participation increases of 55-106% by 2060. The hordes are heading for the hills, but navigating the backcountry requires sound risk-assessment and terrain knowledge. Enter Sperry, who wants to enfranchise backcountry users while keeping the sport safe. His mission is of particular importance in Colorado, which sees more avalanche deaths than any other state. This is due to the tempestuous nature of the state’s snowpack, the sheer number of backcountry recreators, and the ease of access to dangerous avalanche terrain. This past week, a series of storms prompted CAIC to raise their forecast to a Level 5 “Extreme” in an unprecedented five zones around the state. Videos of avalanches sliding onto I-70 and burying cars garnered national attention.

Even resort skiers aren’t guaranteed safe passage on the mountain; inbounds avalanches evince that the natural phenomenon is an inherent risk of skiing. Resort patrollers work to mitigate the risk of slides, but in the backcountry, there is no such service. In untamed terrain, the consequences of poor decision-making can be fatal.

The silence of snowflakes is profound; resort cacophony is almost inconceivable at the summit of Mt. Victoria. To the left of a hit called Coin Slot (as wide as it sounds) is an unnamed chute dubbed West Couloir by Sperry. Getting there involved a bit of bushwhacking, ridge-humping, and cliff-descending, but the reward was a torrent of white falling 2000 vertical feet. The route was made more impressive by its vantage of I-70 squiggling along the floor of Tenmile Canyon. Fall-line was a flowy forty degrees and percolated with small spruce. I gave carte blanche to the mountain, schussing down-chute in a symbiosis of man and mountain. The toy cars on I-70 grew larger in my peripheral.

"Backcountry can be like a single slice of the best food you’ve ever eaten—sushi, Jamón ibérico, perfectly cooked or raw or whatever—but really just a slice of the perfect life. Nirvana in the carve."

I must have let out some powder-brained expression of glee; after coasting to a stop, Sperry radioed me: “Hey giggles—having fun?” As Colorado's growing number of like-minded recreators will attest to, backcountry skiing is fun. And beautiful. And humbling. Sperry says it best: “Backcountry skiing is the root of the sport...getting away from the mechanized form of the sport returns one to a time of the simple pleasures. Our society has become a place of gluttony and hedonism, quantity and quality. Resort skiing is like a supersized Big Mac plus bacon and a Vanilla Shake with added sugar. Backcountry can be like a single slice of the best food you’ve ever eaten—sushi, Jamón ibérico, perfectly cooked or raw or whatever—but really just a slice of the perfect life. Nirvana in the carve.”

Comments ()