Forrest Galante: The Modern-Day Charles Darwin

Except biologist Forrest Galante is not searching for the origin of species, more like auditing the books, and in a few very successful instances, erasing names from the roster of extinction.

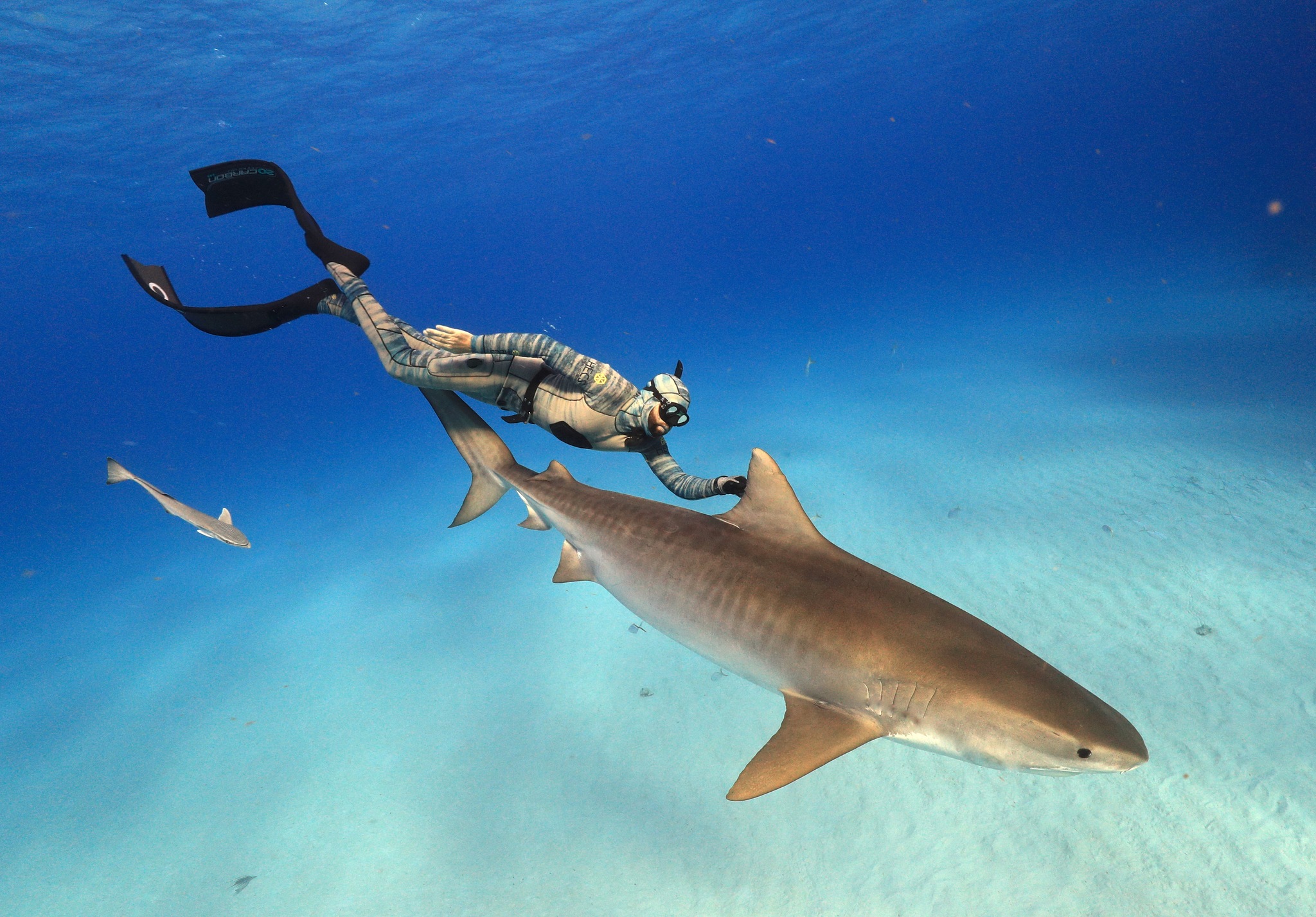

As host of Animal Planet’s Extinct or Alive, Mr. Galante sets out looking for animals long-presumed to be extinct, or as he put it, “gone from the planet, wiped off the face of this earth.” His searches have cast him across 46 countries. In the process, he has been bitten by sharks and venomous snakes, mauled by a lion, charged by a hippo, stung by a man-of-war jellyfish, and stabbed by a stingray.

“Shit happens, like for real—the bee stings, the food poisoning, the allergic reactions,” he says. “I flew into a cocaine dealer’s airstrip in the middle of the Amazon just to gain access to caimans [large reptiles closely related to alligators that can grow to more than 13 feet in length and weigh up to 880 pounds]. These are all real things that we did, and they are all filmed and on the show and part of the challenges we face in order to do the work that we do. The reason we’re so successful is because no one else is doing it. It’s very dangerous and very difficult. And I love it!”

Last year, off the eastern coast of Africa, Mr. Galante captured camera footage of a Zanzibar leopard, a big cat that had been classified as extinct for 25 years. More recently, during an expedition to the Galapagos earlier this year, he found a female Fernandina Island tortoise, a species not seen for more than a century. The finding is one of the most significant wildlife discoveries in decades.

I caught up with Mr. Galante at the wildlife film festival in Grand Teton National Park last month. I specifically wanted to ask him about his early childhood growing up in Zimbabwe and how that experience possibly shaped his perspective of wildlife conservation and influenced his career.

Forrest Galante: As I sit here in this beautiful lodge looking out at a few bison roaming around it’s probably the closest thing to Africa that I’ve seen in North America, outside of Alaska. Where I grew up, basically just like this, overlooking a valley and a lake, at any given time, you could see megafauna, large animals roaming the plains of Africa. But sadly that is something unique to the African continent, except for very small microcosms in South America and at one time Southeast Asia, and of course, at one time here. It has disappeared from the world, and it’s disappeared because of human impact and hunting pressure. Growing up in Africa, I witnessed the disappearance first hand. Watching the numbers of large animals diminish shaped my entire being with regard to becoming a biologist who focuses on extinction. I realized that to study those creatures that are not long for this world and try to preserve them is the most important work.

DB: One of the things the conservation movement and environmentalism rarely discusses is the effects of military action in the world on ecosystems and species. Coming from Zimbabwe you would have seen the devastation war and civil conflict wreaks on the landscape.

"What right do we have to take over a habitat that’s been there over millennia?"

FG: Not just directly but indirectly as well. Zimbabwe went from a country that was super-affluent to one that was poor and starving in the span of just 10 years. Every tree suddenly was needed for firewood or building, every animal for food, and that’s an indirect result of conflict. That’s terrible. Culturally, there were many things the Shona people where I’m from in Zimbabwe would not touch, never dream of eating because they had always been affluent. But now, when they’re starving to death, those traditions and cultures go out the window in order to save themselves. That’s terrible for the people; it’s terrible for the culture, and it’s certainly terrible for the wildlife.

DB: When you consider North American history, for example when bison roamed from Montana to Texas, and then compare that time to now, where parks like this exist for the most part as natural zoos, what does that say about the future of wildlife conservation and is preservation from extinction our only recourse? Is that where we are now?

FG: Well, just think how sad that is. It’s terrible, actually. To get a glimpse of what the natural world was like - because this is just a drop in the bucket of what it should look like - and see how stunning it is and how much wildlife there is and then realize it’s gone, to me, is horrific. It’s not fair. So, yes, where are we at in this world? Well, there are eight billion of us. We’ve taken over and pushed out room for the wildlife to be natural. And that’s the problem. It’s overpopulation. It’s an encroachment on habitat. What that means is managing what remains because these little pockets, like this beautiful one we’re looking out at here, deserve to be saved, and the species that reside in them and their carrying capacities all need to be managed.

DB: How do you envision managing it because management means different things to different people? North America, where we had large landscapes to set aside, is very different from circumstances in other parts of the world, like India for example, where establishing a wildlife refuge for tigers means displacing large populations of people. In our effort to preserve wildlife, what is the criteria for establishing an equitable balance?

"Displacing a large population of human beings is absolutely worth it for a small population of wildlife."

FG: Displacing a large population of human beings is absolutely worth it for a small population of wildlife. If human beings own every piece of wilderness, where’s the balance, where’s the space for wildlife? What right do we have as just another living organism to take over a habitat that’s been there over millennia? That’s the difference between being a humanitarian and being a biologist, and on a bigger scale being a realist? There are 6,000 tigers left in the world. There are eight billion people, two billion of them are Indian. No offense to the Indian people - I’m not a humanitarian, clearly - but the tigers deserve a little land.

DB: What are your objectives in the conservation movement? What would you like to see happen in the next five, ten years, or even the next generation?

FG: I don’t want to see just one thing done. I don’t want to save the bison. I don’t want to save the tigers. I want to see a generation of young people who care about saving all of it together. The message I tell on my show is about hope. We live in a time when we are so callous of ecophobia - a condition, by the way, I absolutely hate! - because species extinction and global warming are in the headlines every day, to the point that you feel nothing anymore. Rhinos are going extinct. Okay, next. I mean, you feel nothing because you see and hear it every single day, so flipping that on its head, giving it a positive message and not saying look at how doomed we are but rather look at what’s left, look at how great these beautiful things are that still exist. That’s the story I tell on Extinct or Alive. Whether I find the extinct animal or I don’t find the extinct animal, either way, along the journey we’ve encountered this incredible habitat, that incredible animal, this amazing interaction and all those little pieces of the puzzle, those little things that still exist in the ecosystem are so mind-bogglingly fantastic! That’s the message I want people to take away. The culmination of all those little things to inspire a generation of people to care about conservation, to care about preservation is what I want to see.

DB: How do you feel about working in television?

FG: I love it. I absolutely love it. I love it because it allows me to reach such a large audience. It’s nice to be able to tune into television that is not just entertaining, but that is scientifically valuable.

Watch the new season of Extinct or Alive, which airs beginning October 23 on Animal Planet.

Comments ()