Following the Ganges - Source to Sea

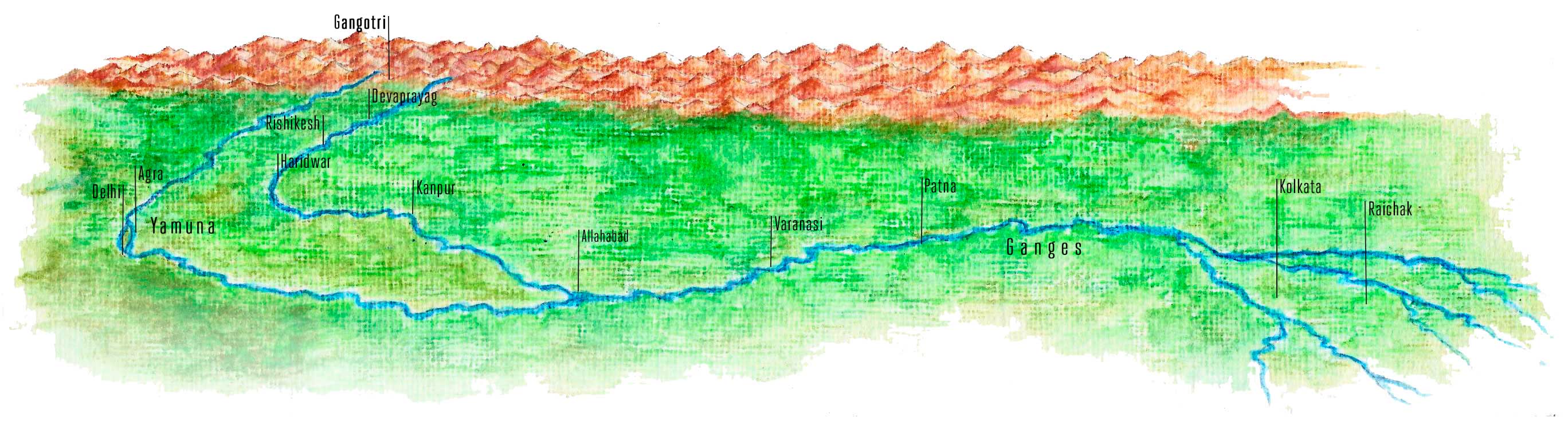

A group of explorers follow the holy waters of the Ganga from source to sea - documenting the river and the world around it by climbing to the top of the Ganges watershed, following it through the Himalaya, across the Gangetic plain and through the delta to where it kisses the ocean.

Camp 1, 17300 feet - Gangotri Glacier, Garhwal Range, Indian Himalaya

Just before sunset, the snow starts to fall. The flakes are wet and heavy. Jake Norton looks up and says as much to the sky as to us, his climbing partners, “This feels like one of those monsoon storms that stick around.”

Dave Morton and I listen to Jake’s words but there is nothing to do except button up. The three of us are exactly where we wanted to be – high in the Garhwal Range of the Indian Himalaya standing at 17,500 feet atop the giant Gangotri Glacier, surrounded by 23,000-foot peaks, most unclimbed. It is the birthplace of India’s sacred river, the Ganges. It is also a four-day walk — much of it through treacherous, rocky glacial moraine — to any whisper of civilization. And due to our proximity to India’s northern border, Indian law prohibits satellite phones. International tensions with Pakistan are higher than normal, boiling even. We are highly aware that any rescues requiring help, are out of the question.

We came to this spot to claw our way up the un-climbed Chaukhamba IV, a 23,000-foot, glacial-clad granite monster standing like a sentinel protecting and feeding the Gangotri Glacier at its feet. But avalanche conditions are ripe so we have targeted another 22,300-foot peak on the west side of the glacier. It too has never been climbed. We are poised to move upward tomorrow. Ropes, helmets, carabineers, crampons, and ice axes sit outside our tents.

This record-breaking, stubborn monsoon season might say otherwise though. As darkness seeps over us, my ear tells me he might be right. The wet heavy flakes which we had seen before, have changed. The normal soft sound of falling snow has morphed to a frozen, miniature hale. Miniature tap dancers performing on our nylon roof, I think. We lie in our sleeping bags cracking jokes about our remote abode. Who packed snowshoes/skis? But each of us is intently focused on the sound of the storm. I try to keep worry to a slow percolate.

As the damp night lists, we continually shake accumulating snow from our tents. We take turns shovelling every two hours to keep the ventilation from sealing. The thought of quiet suffocation keeps me awake.

The steady creaks and moans of the glacier, that kept me awake previous nights, have subsided. They reminded me of a bird flying into my kitchen window this summer. Although sometimes the sound is a higher pitch: a steel bar hitting a high-tension cable. Electric almost. The steady roars of water pouring down the glacier in small creeks larger than the ones I live near in Colorado, have also gone mute. Just the icy dance of snow on our tent. I wonder if the haunting loon-like call of the male snowcock that resembles a pheasant, will awake us in the morning like it has prior. I have yet to hear him though.

Sometime around midnight a new sound jolts Jake and I upright in our bags. A low rumble... no distant thunder... no echoing giant thunder. Avalanche. At first we hear it from afar – high up on Chaukhamba, I presume, but steadily the rumble grows louder, stereo even. Jake and I look at each other. “How far are we from the mountain?” I ask starting to eye my boots. Jake assures me we are fine. Ten minutes later another roar. Even louder: Harley Davidson-esque. Jake eyes his boots. We conclude our mile plus distance is enough... we hope.

For the next five hours, the avalanches continue. Their sounds vary between distance thunderstorms to the crack of artillery fire and explosions – probably house-sized ice blocks getting freed from their hanging yards above. Some avalanches last over a minute. Throughout the sleepless night, I count 36.

At 5:30 A.M., after shoveling our two tents repeatedly throughout the night, we decide our climbing mission is over. If we don’t move, the monsoon won’t let us. It is time to pack up and fight our way down with as much as we can carry. As I mine for buried tent stakes, I measure over three feet of snow (one meter). It is still snowing, hard. We are in a gray and white soup with light so flat, I’m disoriented when I stand. Having grown up in the Rocky Mountains and spent the majority of my life in snowy environs, I have never seen a 12-hour surge of frozen moisture like this ever in my life.

Over the next six hours we post-hole through thigh concrete-like snow, straining under oversized loads. Our climbing ropes remain behind. We mark them with GPS coordinates; optimistically hoping someone can find them later. We only make the three miles to our advanced base camp where we find one tent completely flattened by snow. Dave, who has guided the seven summits and stood atop Everest seven times, says it is the “most worked he has been in a long time.” I can barely smile at the comment. I’m shattered. And our source to sea Ganges journey has just begun.

Having visited the Ganges years before on another assignment for National Geographic, I knew just enough about this world through which the river flowed to realize an important thing: A source-to-sea mission, on paper, is simple. Doing it would be daunting. The mind-boggling logistics involved in any source-to-sea mission are troublesome. In India, they can be perplexing. Communication near remote headwaters is limited or nonexistent. The permit process can suffocate you in bureaucratic paperwork and take six months to a year. It took nine months to initiate the process of hiring a helicopter for a scouting/ filming flight. The actual trip would last six weeks.

Our first challenge beyond the logistical minefield of permits, communication, and transportation would be capturing the passion and reverence people exhibit for their beloved waterway, which drains the southern Himalaya. Everyone from pilgrims and politicians to socialites and sadhus flock to the river’s banks to pray, bathe, or merely admire its power. Many rivers worldwide often go unnoticed except for hydroelectric operators and a few recreationalists (boaters and fishermen). But in India, the public embraces the Ganges with open arms.

This collective, spiritual hug by the hundreds of millions using the river, however, comes with costs. Pollution and a lack of environmental awareness are visibly notable across much of the watershed. And in many areas, the challenges are compounded by a simple mindset flowing through the same people that revere its sacred flow: The river is God, thus it is all powerful and immune to the threats of overuse, contamination, and environmental degradation. In short, people believe the curative powers of the Ganges will not only heal us, but also itself. It is an illogical environmental conundrum— the Ganges paradox, if you will.

For me, this paradox sparks a question: If the physical river dies, what happens to the spiritual power?

Many Indians I asked brush away the question suggesting the Ganges can’t die, but admit they are concerned about pollution. One woman who has lived on the Ganges’ shores for 18 years boldly stated, “If the Ganges dies, we all die. Society dies.” My friend and translator for the trip, Madhav Anand, who grew up traveling the river, says, “After years of cleaning our sins, now it is time to clean the sins placed upon Ma Ganga.” It appears many agree. India’s new prime minister, Narenda Modi, won the last election on a platform that included cleaning the Ganges. In July 2014 his administration proposed a 340 million dollar budget to do just that, fueling hope across India.

Arriving in August 2013 on the heels of a record monsoon that triggered a glacial outburst flood, our first river lesson presented itself: The Ganges gives and takes away. Over 6,000 people died, and thousands more were reported missing. Miles of roads were washed out and complete hillsides scoured naked. Entire villages were swept into oblivion. The communities we traveled through mourned with stoic resilience.

Slightly defeated by our abandoned climb, we push downstream past Gaumukh, “the cow’s mouth,” where the Ganges pours out beneath the collapsing foot of the Gangotri Glacier. This transition of ice to river is spiritually powerful and many Hindu pilgrimage here. The exact location, however, is moving upstream at roughly 60 feet a year—the hand of climate change at work.

And then after weeks on foot, we return to the wheeled travel of 4x4s and move downstream through the scoured canyons of a gravity-fueled river. The roads that were washed out when we came in are now repaired, barely. “It feels like we are driving on a sandcastle,” says Dave.

The sacred headwaters are clearly behind us. Time to start looking downstream.

Industry on the Banks: Deep Inside Kanpur’s Tanneries

As we walk inside, I can taste metal in my gums. It feels like crossing a doorway from an air conditioned room into a desert but instead of entering a wall of heat, I’m met with a vapor cloud of chemicals—hot, sticky, metal-tasting chemicals. Ammonia I recognise, then something else. I can’t identify it. Before the thought has a chance to linger, all of my senses are overwhelmed. Burning nostrils, watering eyes, raw throat. I look back at our crew and see everyone waging their own battles—blinking eyes, covering mouths. Everyone fights the urge to turn around. The cool, misty air of the Himalayan foothills, some three hundred miles upstream, is already a distant dream.

As we move further into the green glow of this cavernous factory, I begin to hear the slosh of something slapping liquid. We turn a corner and see sinewy workers, their bodies beaded in sweat and their calves wrapped in makeshift plastic socks. Thick, orange rubber gloves protect their hands. They rhythmically grab buffalo hides with long metal hooks. Four two-man teams work silently in perfect unison, never speaking. Some teams hook hides into concrete tubs full of silvery, gray liquid. Others pull the hides from one bath to the next. Whack, slap, slosh, whack, slap, slosh. Everyone moves in perfect timing, efficiently. Years of repetition.

Despite my now burning, watering eyes and swelling nausea, I’m right where I want to be—deep inside one of the most controversial industries on the banks of the Ganges. It took us four weeks of travelling the Ganges downstream to get here and two days of negotiations to gain access.

Leather textiles are part of Kanpur’s DNA. It is also sensitive. During British rule, this Indian city evolved on the banks of the Ganges because textile companies could easily transport their goods to market from here. It made economic sense. In 2009, India was producing 8 percent of the world’s leather supply—so leather remains an economic engine. Much of it goes to shoes.

Despite their economic success, tanneries have been severely criticized for polluting water supplies—specifically the Ganges—with heavy metals like chromium, a hardening agent in leather production.

Improperly handled, chromium quite simply is nasty business. It is linked to causing lung cancer, liver failure, kidney damage, and premature dementia. As I look at the workers in front of me sloshing and sweating, shirtless, I can’t but wonder about their health.

There are approximately 400 operational tanneries in Kanpur today. That is after some 70 were shuttered due to pollution concerns. The remaining ones are required to recycle all their water. We visit two facilities, one large and one small, and both have recycling systems, but both require electricity to run their pumps. And electricity production is notoriously unreliable in northern India. I notice power outages occurring six to eight times a day. And when it does, milky, silvery-grayish water spills down overflow ditches in the streets, most likely headed to the river.

Beginning at the headwaters, we have taken water samples every few hundred miles at key locations. Kanpur is one of them. The samples were later tested for 21 heavy metals at a registered drinking water facility in Denver, Colorado. Not surprisingly, our Kanpur sample shows a steep spike of chromium. It is one of the highest heavy metal samples we record.

Our data isn’t alone. In 2013 a study in the news showed that tanneries were pumping out 30 crore liters (roughly 79 million gallons) of contaminated water into the Ganges a day but the city’s treatment facility could handle only 17 crore liters (about 45 million gallons) per day.

Later in the afternoon teammate Jake and I photograph kids playing among chromium-laden leather scraps on the banks of the Ganges. My eyes still burn and my nausea lingers. It is a joyous scene full of laughter and energy. The sun is setting and I look out at the lazy, chai-colored flow of the Ganges. Surprisingly, no one is arriving for evening aarti prayer like we have seen consistently upstream throughout the terraced farmlands of the Himalaya foothills. I assume it is because I am in a predominantly Muslim section of the city and the Gan- ges isn’t considered as spiritually significant. But I witness few Hindus visiting the river anywhere in Kanpur, just one family doing laundry and some teenagers practic- ing break dancing. After learning a few Indian moves, the breakers tell me they are Hindu and that they do pray to Ganga but “never swim or bathe. It is too dirty.”

The Pyres of Varanasi: Breaking the Cycle of Death and Rebirth

When you step off a wooden boat onto the banks of the burning ghat in the oldest of India’s cities and you weave through a maze of funeral pyres hissing, steaming, and spitting orange embers into an inky night and you feel the metronome clang of bells vibrating inside your chest and a wave of furnace-like heat consuming everything in its reach, you realize how removed you truly are from the ritual of death.

[su_quote]I’ve traveled through international hot spots where life is cheap. I’ve also lost my fair share of friends and family. I don’t feel sheltered from the bony hand of death. But when I stepped on Varanasi’s famous cremation ghat, which runs 24/7, burning hundreds of bodies a day in plain sight, it dawned on me how physically distant most of us are from the departed. In the West, the dead are typically hidden—taken away—either to be beautified for a funeral or to be cremated, depending on beliefs. Either way, bodies are rarely seen again. Some might argue it is civilized, cleaner, or perhaps just emotionally easier. Or maybe it is the modern world’s subtle way of hiding from the inevitable.[/su_quote]

Funeral practices vary worldwide. Of those I’ve witnessed, few are as transparent and raw as the Hindu ritual on the banks of the Ganges River. The Hindu believe that if a deceased’s ashes are laid in the Ganges at Varanasi, their soul will be transported to heaven and escape the cycle of rebirth. In a culture that believes in reincarnation, this concept called moksha is profound. The holier the place, the better the chances you achieve moksha and avoid returning to Earth as a cow or a cricket in your next life.

Since many believe Varanasi has been inhabited for 5,000 years (which would make it one of the world’s oldest cities), it is considered to be the most sacred of cities on the banks of the Ganges River. People come from all over to pray, collect sacred water, bathe, and yes, attend to their dead. Some even come to die.

Thanks to the peaceful manner of our translator/fixer Madhav, a Hindu monk, our team was given access to document this sacred ritual. Within minutes of arriving, sweat streamed down my face. Teammates Dave Morton and Ashley Mosher filmed next to me. They struggled to breathe in the blasting heat. I could barely even see through my cameras.

At first, something seemed wrong about us being there. I didn’t feel entirely comfortable documenting such private moments. I wanted to ensure we were being respectful as we documented this foreign tradition in a foreign land. Something compelled me to keep looking, to keep shooting. Perhaps it was the simple commonality in it. No matter what we do or believe, none of us gets out alive.

At 4:30 a.m. the next morning, we returned. A blood red sun was rising across the river. Only one pyre was burning. The bells had stopped. Smoke and ash were everywhere and workers meticulously collected human ash and bone fragments to dump into the river. Goats and dogs roamed freely and steam rose from the ground.

Like most things in India, though, there is a parallel story. The demand for wood, particularly hard wood, taxes Himalayan forests. Burning one large body can require up to 1,100 pounds of logs. In turn 50 to 60 million trees are consumed annually in India alone. Electric or gas-fired crematoriums have been built but both depend on unreliable energy sources and so most still prefer traditional methods. As the sun continued to rise, I noticed three boats towering with timber coming downstream. Raj pointed out one electrical crematorium nearby. It was closed.

Not everyone can afford the cost of funeral pyres either. Even the cheapest wood is beyond the reach for much of the poor. Many bodies are discarded into the Ganges partially cremated or not at all. Estimates say 100,000 bodies of various cremation levels are tossed into the Ganges each year.

By 9 a.m., the Indian sun blazed above the Ganges. Three fires were now burning. My hair was covered in ash and I was pouring sweat again. As I walked through the wood-splitting area, an old woman suddenly emerged from the shadows and held out her hand, the internation- al request for money.

Raj, guiding us out, casually said, “She lives here. Her family left her. She has come to die and needs money for cremation. Want to donate some rupees for her wood?”

Kissing the Bay of Bengal: Celebration, Reverence, and Mystery

Drenched, shivering, and fearful our cameras are dying quick deaths in the downpour, our team flees for the hotel in a taxi carefully decorated with scores of lights and an orchestra of paint. Rain pours from the heavens in volumes I’ve never experienced, not even in rain forests. Everything floods—roads, restaurants, shops. Our hotel lobby is shin-deep in water by the time we arrive. Amazingly no one seems to notice or care. The world here is celebrating. Trombone bands march, revellers dance, and lines of floats carrying intricate Hindu statues all slowly migrate toward the Ganges, where they will be heaved into the flow as offerings. Some sink, but most wash ashore downstream, joining hundreds littering the banks.

After 40 days of chasing this holy river from its thin air source high in the Himalaya to the edge of its delta here in Patna, our team has grown accustomed to such celebratory reverence. We have also grown fatigued and are racing the clock to complete our mission. A record monsoon delayed us in the headwaters and now we are slowed again, drenched souls stalled in the eye of a raging cyclone. A deluge of rain and some 400 river miles stand between us and the point where the Ganges River finally kisses the Indian Ocean at the Bay of Bengal—the end of our journey.

Over the next five days we hopscotch downstream via train, ferry, rickshaw, bicycle, and more colorful taxis— some with windshield wipers and lights, some without. At times I feel like a fish swimming through the river, upstream at night. And everywhere, people wildly, passionately celebrate Durga Puja, all dumping their handmade Hindu idols into the river.

I marvel at how each and every mile of this sacred Ganges is so deeply loved and intertwined with local rituals. But in many cases, it looks loved to death. The religious symbols and offerings that represent devotion frequently become pollution downstream. Lead paint and plastic seem ubiquitous.

To attain a better grasp of the river’s health, we bring water-testing equipment the entire way. The results in many locations are as expected. Heavy metals and nitrates spike. And in certain troubled areas, oxygen levels plummet. On the Yamuna River, the largest tributary of the Ganges carrying the runoff of New Delhi’s economic boom, we test a section flowing past the Taj Mahal in Agra. Not surprisingly, the river reveals zero dissolved oxygen— a dead river. When we wade out among garbage, sewage, and who knows what else, the data merely confirms what our senses are screaming—the Yamuna River in Agra is far from healthy and full of garbage and waste—every putrid kind.

But this is the amazing part. When we meet the Yamuna again downstream at Allahabad some 300 miles downstream and roughly halfway down the Ganges, our samples show dissolved oxygen similar to those found in healthy rivers. Somehow, someway, the Ganges is restoring itself on certain levels (heavy metals remain high in Allahabad). Perhaps there are some curative powers or obscure minerals that support the river’s ongoing real or mythical health. Either way, it has lasted for centuries.

The British East India Company used only Ganges water on their three-month long journey back to England because it stayed “sweet and fresh.” Scientifically, many point to the unusually high levels of bacteriophages, or just phages—viruses known to eat bacteria which keep disease at bay. But few can explain where and why the antibacterial properties originate. As early as 1896, a British scientist documented thriving cholera bacteria dying when put in Ganges water. And experts have yet to fully explain the river’s ability to sustain and revive its high oxygen levels. It is often called the mystery factor or the X factor.

The spiritual answer often becomes the fallback. Ma Ganga, India’s national river, is god—the creation of Lord Shiva himself, the god of destruction in the Hindu pantheon. Of course it can kill bacteria.

Throughout our journey, my science-based upbringing struggles to accept the spiritual answer. Regardless, I am frequently moved by the open-armed reverence for the river and its healing powers. In India, people face the Ganges daily, yet a civic concern for abusing the river is almost entirely nonexistent. Most believe Ma Ganga will repair itself. One woman told me, “Babies defecate in their mothers’ laps all the time and the mother cleans it. The Ganges is our mother. It is no different.”

Such thinking forms the paradoxical view that perplexes me every river mile we travel. Those that revere it most pollute it equally. And yet, many of those same believers complain that the Ganges is dirty—too polluted to even swim in anymore. The situation, from an environ- mental perspective or logical view, is inexplicable.

After 45 days of chasing this sacred flow 1,550 miles from nearly 18,000 feet and minus 20-degree temperatures to sea level and 110 degrees, we reach the end at Sagar Island. The cyclone subsides and the sun struggles to emerge. I weigh 30 pounds less than when we started. Teammate Jake Norton is 15 pounds lighter and Dave Morton remains the same weight (we suspect he’s superhuman). The air is humid and sweltering and nothing seems more fitting than going bodysurfing. Jake, Dave, and I sprint out to greet the small, glassy swell rolling onto the beach. Even Ashley Mosher, our second camerawoman who is leery about Ganges water, joins us for a dip. The brackish water is bathtub warm but feels delightfully cooler than the air. A pack of children quickly joins us, and laughter echoes across the bay.

As we splash in the water used by some 400 million people upstream, I reflect on this river that is revered and reviled, dammed and diverted, cherished and neglected and in some cases nearly destroyed. Despite all the devotion we witness from aarti celebrations throughout to the Durga Puja offerings, it is easy to wonder if people will realize a simple concept: Sacred and unique as it may be, this river will need more than prayer to survive, de- spite all its healing properties. After washing the sins of so many for so long, when will India effectively clean the sins of industry, agriculture, and devoted love thrown daily in the lap of their national mother, Ma Ganga?

A few days before we depart, my friend Madhav, the Hindu monk who travels with us for much of the journey, says, “The time is now.”

The Ganges River expedition was made possible with funding from Microsoft, Eddie Bauer, National Geographic Society’s Expeditions Council, Ambuja Cement India, and Hach Hyrdolab. The full expedition team includes photographer and videographer Pete McBride, videographers and professional climbers Jake Norton and Dave Morton, and second camera Ashley Mosher. The expedition outfitter was Ibex Expeditions. Peter McBride and Jake Norton's film, "Holy (un)Holy River", recently received another award, this time for the best Nature & Ecology Film at the Bovec Outdoor Film Festival (BOFF) in Bovec, Slovenia. Check out their new website, www.holyunholyriver.com, for updates, trailer, images, and more.

This story was part of the Features section of The Outdoor Journal Spring 2015 edition of the print magazine.

Feature Image: 15,000 ft below Shivling peak at basecamp. Image © Peter McBride

Comments ()