Watercolor artist Elaine Booth has spent her career painting the natural world. But although she hopes to explore “scale and detail in ecosystems, land, and wild places,” with her paintings, she’s aiming for more than mere realism. “When people tell me my work looks like a photograph, it’s quite frankly, insulting,” Booth joked.

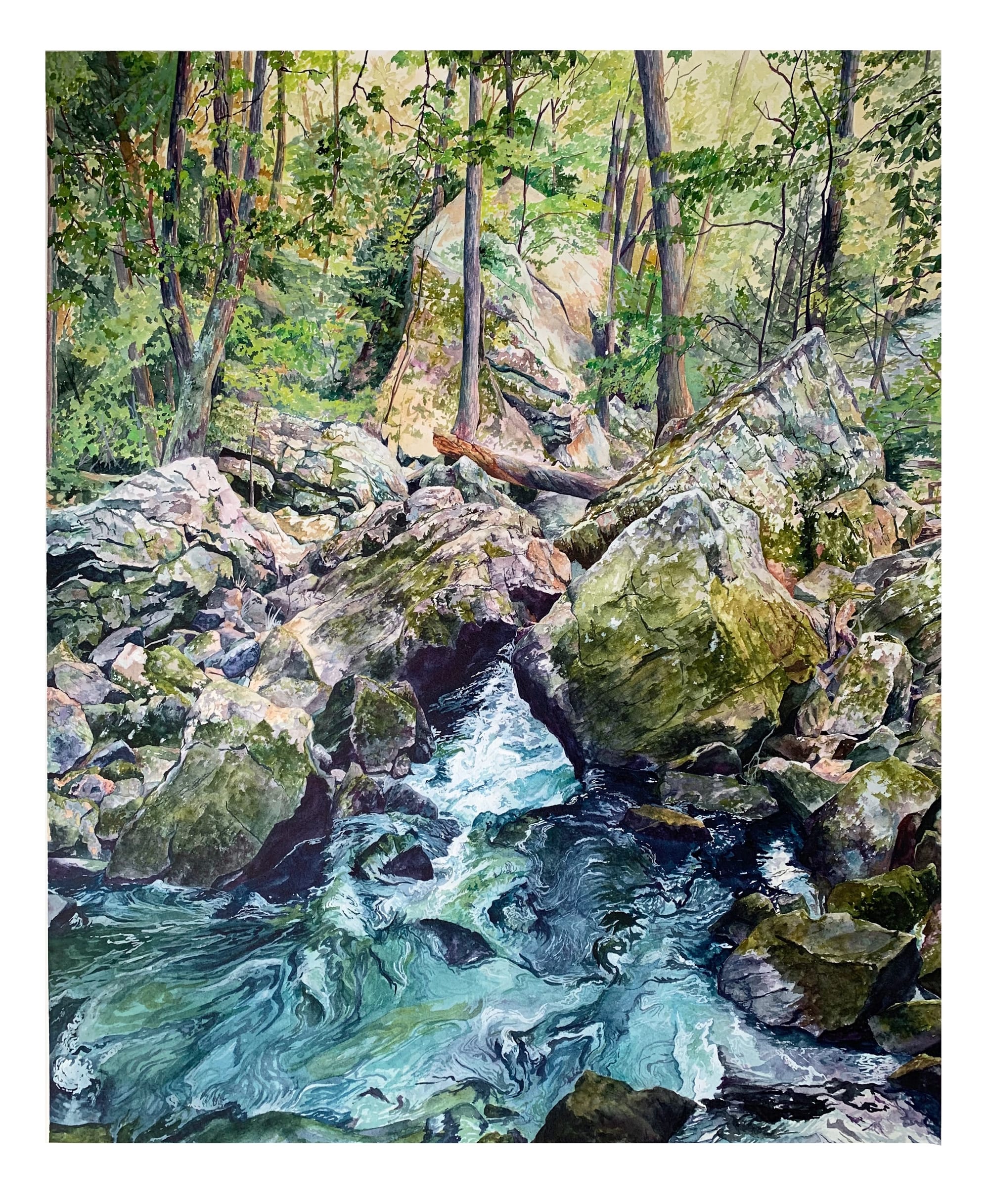

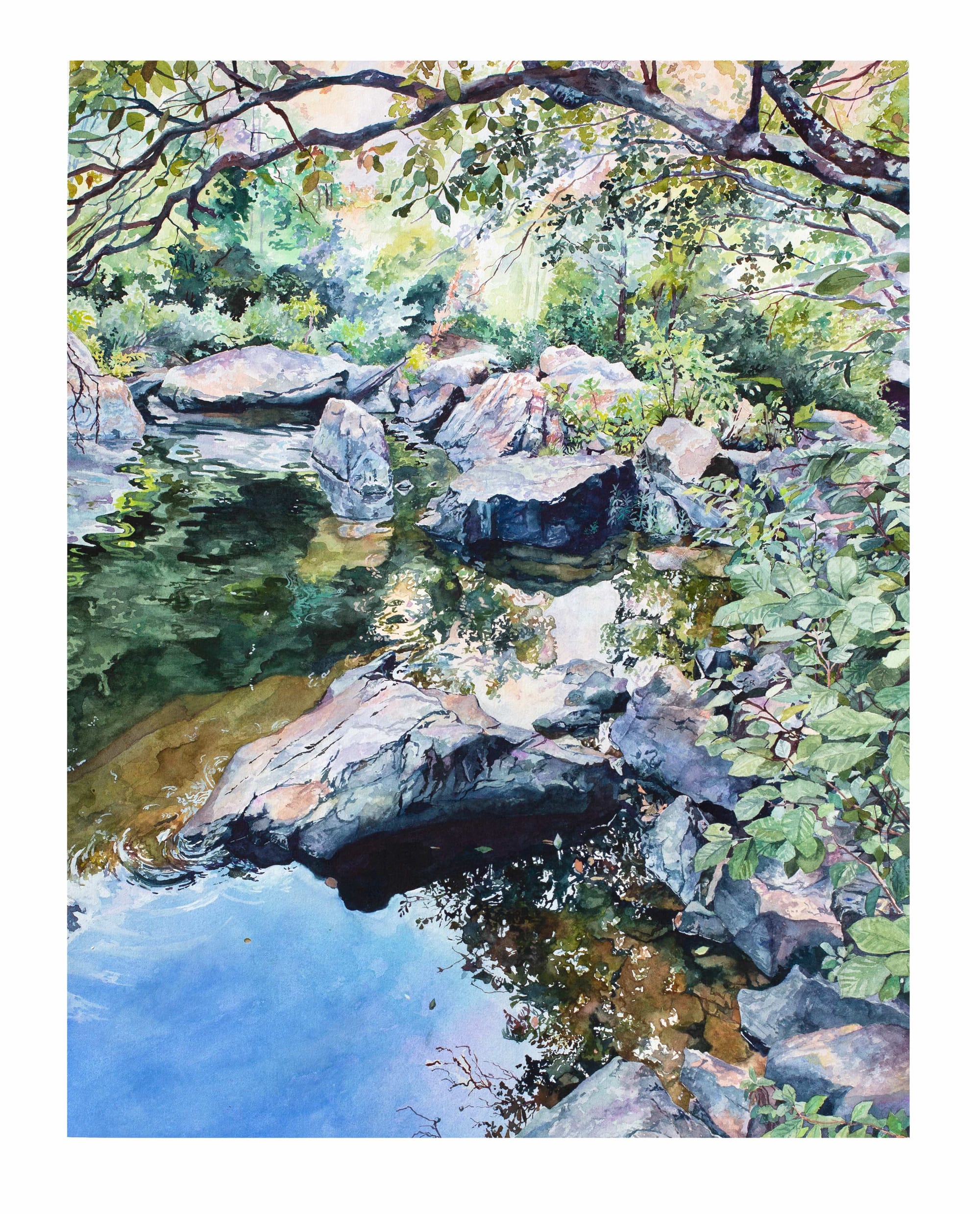

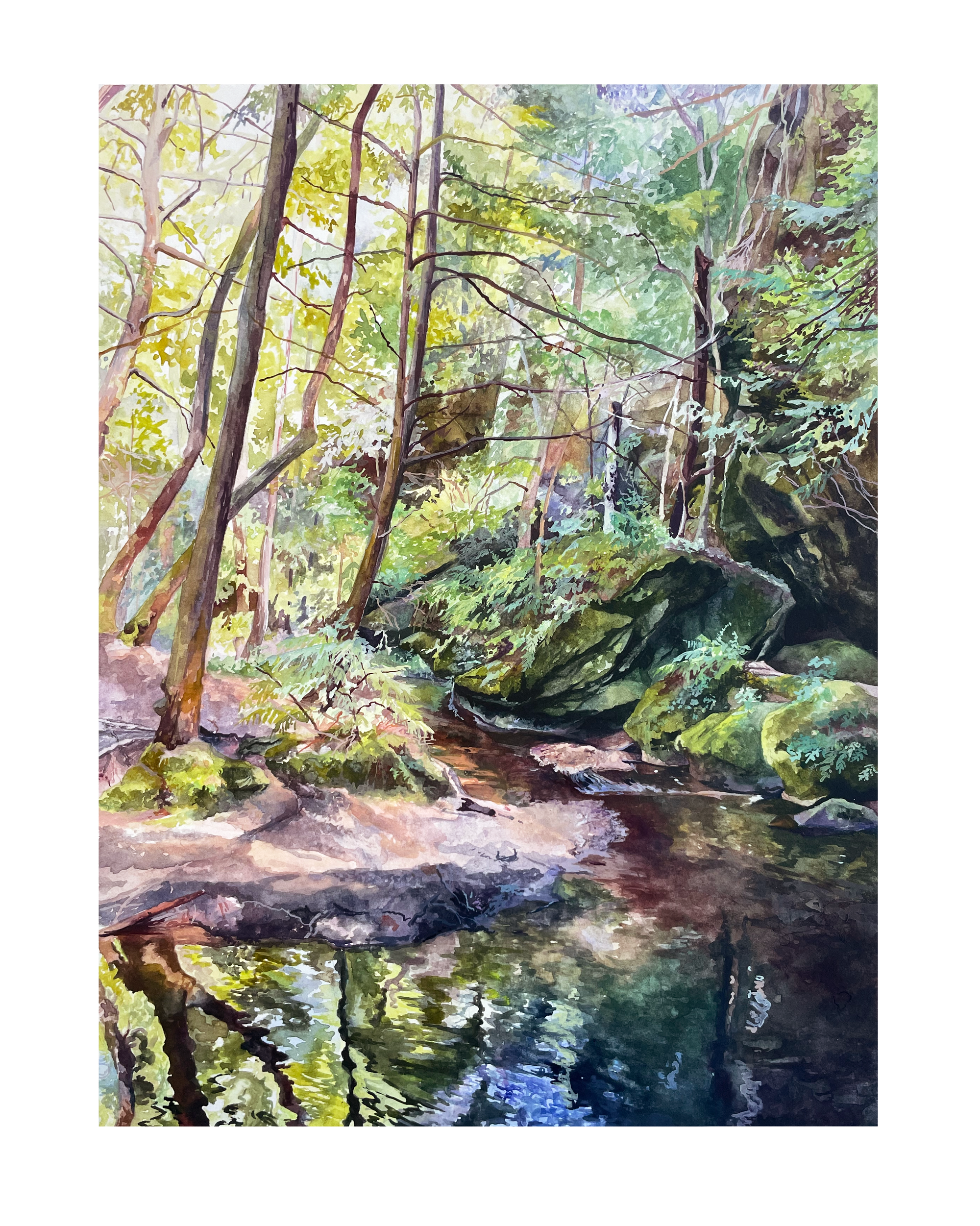

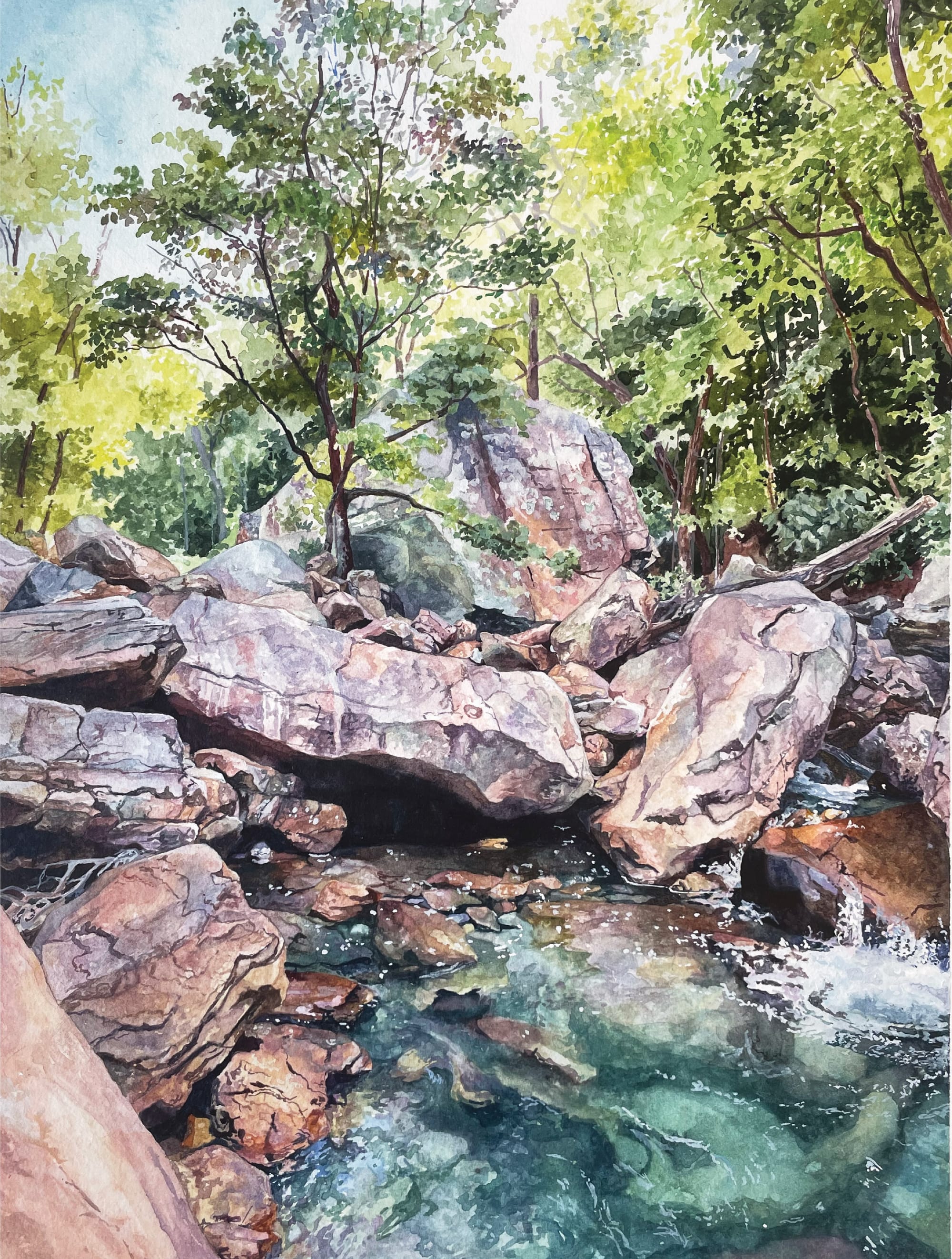

“I know it’s meant as a compliment,” she added, “but photos are very flat. Photos can be beautiful, but they take away from reality, too. I want my work to feel real, not like a picture or a window. I want it to feel like you're there. Like you could dip your toes in the water.”

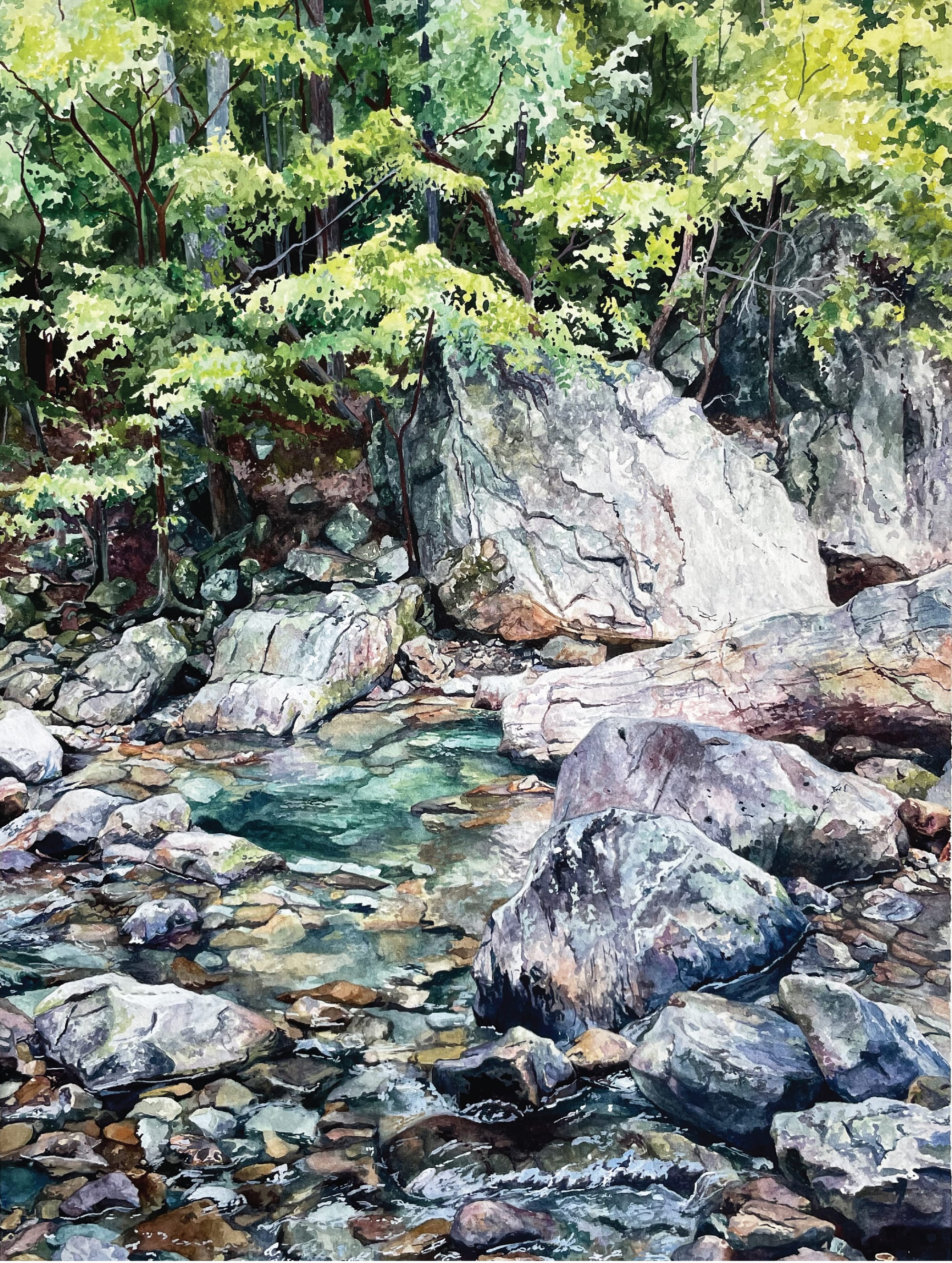

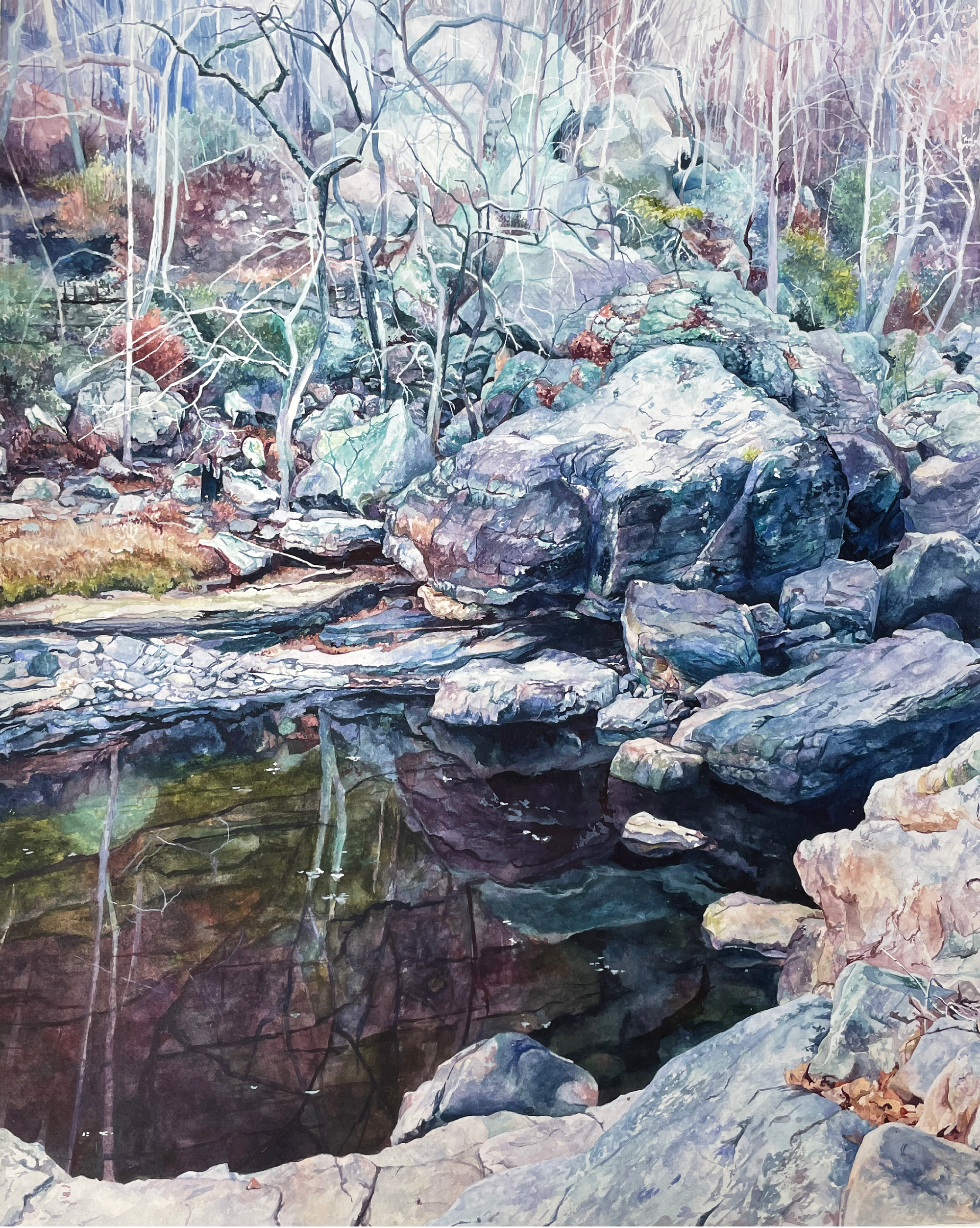

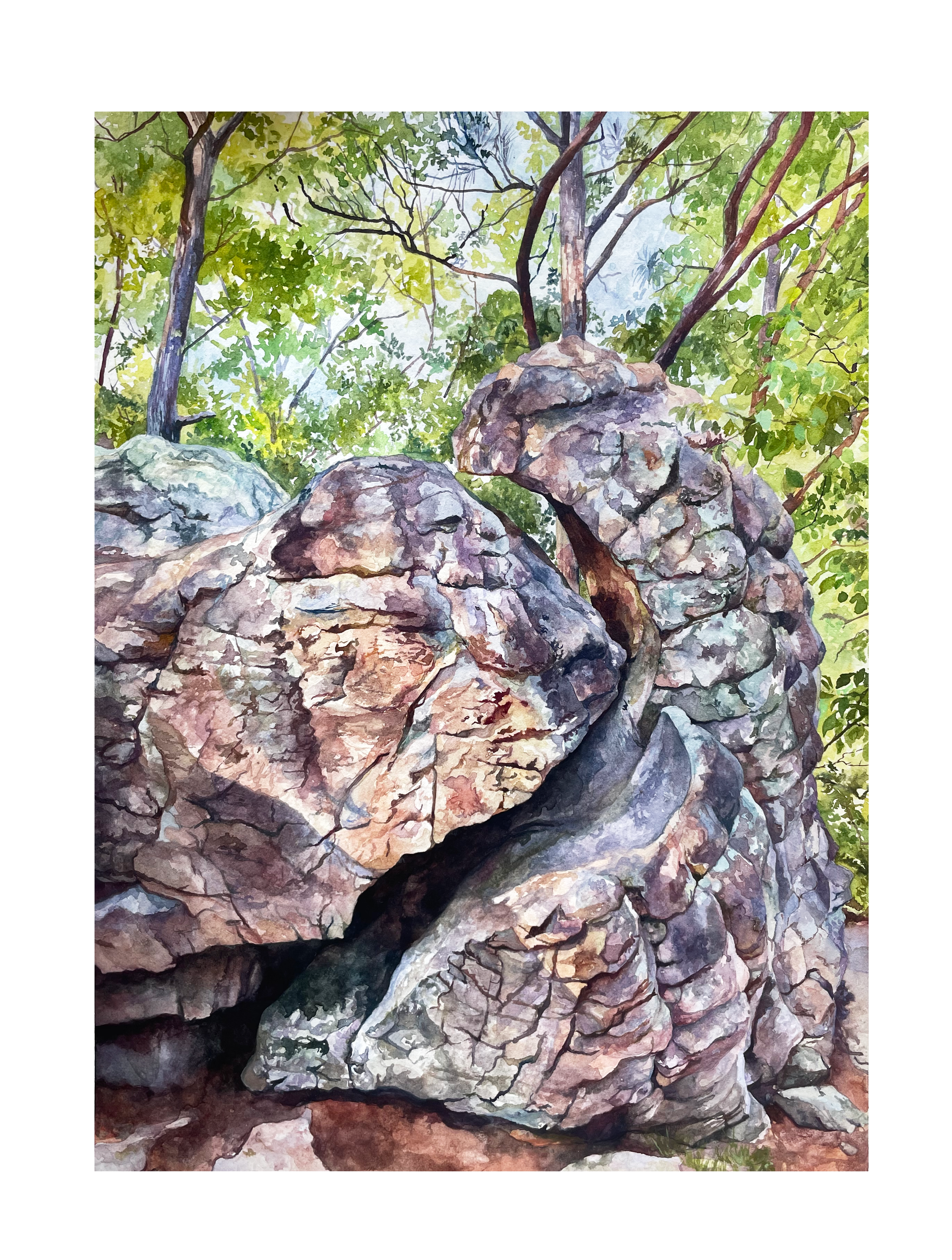

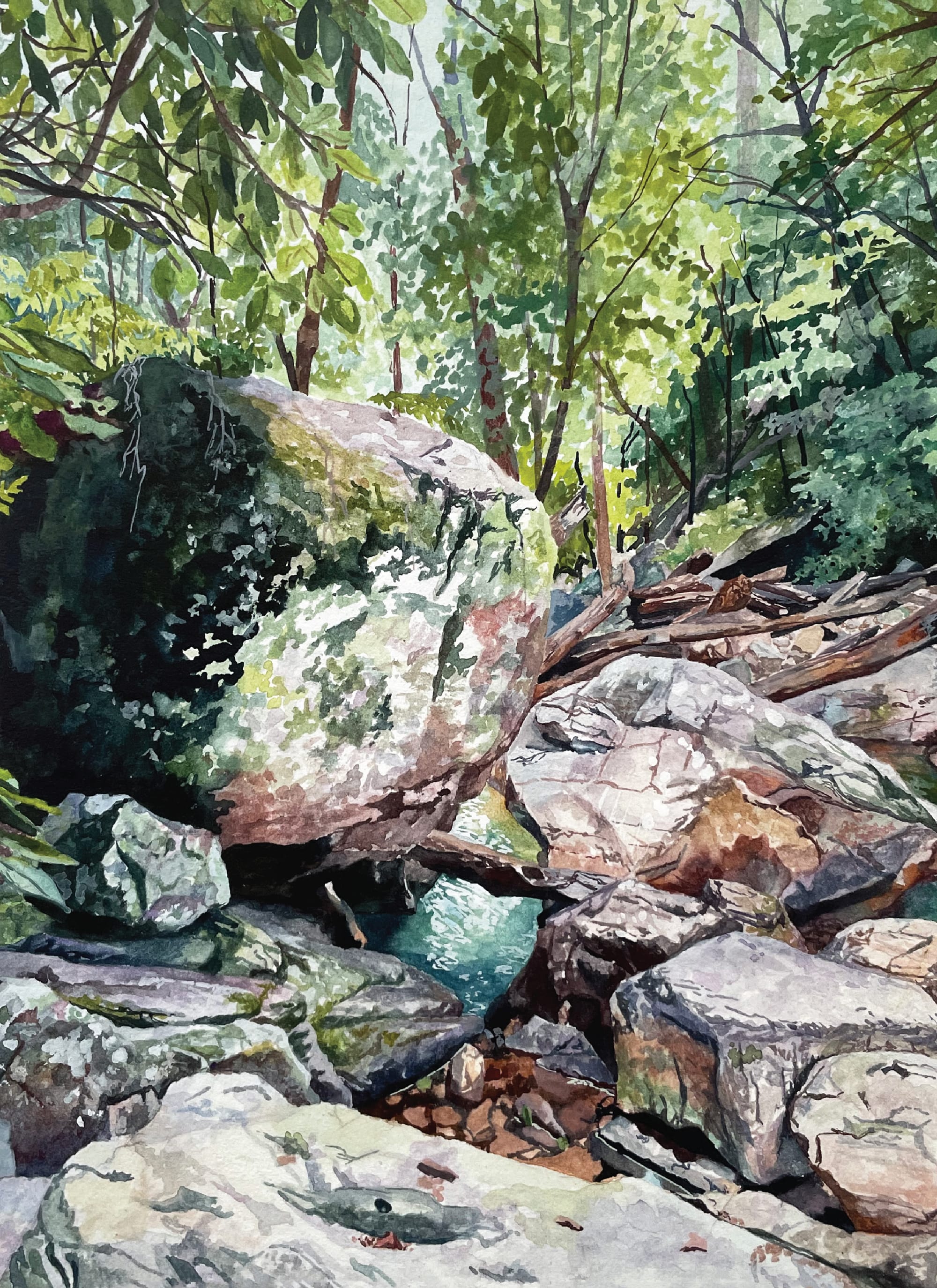

The 28-year-old Booth, based in Huntsville, Alabama, makes her living almost exclusively painting dense southern woodlands. Chiefly, her paintings depict boulder-choked streams rimmed with the deciduous flora of the southeastern United States. Trees and rocks. Water and earth. Humans and animals are never present in her work, and although each of her paintings is inspired by a real location in the natural world, she never reveals these locations. Few, if any, have identifiable landmarks or characteristics.

It was this dichotomy, in part, that made me interested in interviewing her for The Outdoor Journal. In a world rife with geotagging and content creation, the desire to share nature without capturing or labeling it, to depict it as it is, without human influence, feels meaningful.

No people, no names, no recognizable landmarks. Does this make a work of art less relatable? Booth says it’s the opposite. “There's familiarity in anonymity,” she told me. “People will come in and they'll look at a painting and they go, ‘Oh, I've been there. I don't know where that is, but I've been there.’ Or, ‘That looks like my best friend's backyard when we were kids!’ That viewers can have that experience is important to me. I don't want to alienate anyone from my work.”

By the same virtue, a human figure in her work, she says, would torch the viewing experience. “It's important to me that people feel like they are there. If I paint someone into a picture, it immediately shuts them out from the experience.”

Although Booth painted from early childhood, she never imagined she’d manage to make it a full-time career. She studied design at the University of Kansas, and after graduation got a job at the edgy (now-defunct) e-commerce platform Moosejaw. Working at Moosejaw and other gear shops paid the bills, and she had applied to a number of design agencies, but hadn’t landed a hit. After a while, she began to give up on the outdoor design world and started studying for the LSAT, considering going to law school.

Then, on the eve of the coronavirus pandemic, her world went into a nosedive. She was dumped by a boyfriend right before the pandemic lockdowns. The lockdowns, of course, also meant no more law school. “I was extremely broken-hearted,” she said. “I was stuck in my house, living by myself.”

Things got worse. A few months later, after lockdowns were lifted, she was axed from her job at Moosejaw. “I got fired without any warning, basically for being too sad,” she explained, laughing. “They were like, ‘You don't fit with the vibe of the company anymore.’ I was already so depressed. My mental health was so bad. Then, I lost my job. Things just tanked from there.”

Isolated by the pandemic, out of work, out of love, living alone in Kansas, “there was nothing to do but go on walks and use the dinky little watercolor palette that I had in school,” Booth said.

She hadn’t painted in ages, but it brought a little light back into her life.

And then… people started buying her paintings. She was posting her work on social media, and it was gaining traction. People were commissioning her to paint original work. Money was actually coming in, in exchange for her art. It wasn’t a lot, but it was a start.

That winter, she moved back in with her parents in Alabama, and began working on her art full-time. She thought she’d be back in Alabama for a few months, to reset. Fast forward nearly five years, and she’s a professional artist with her own studio, making more money than she ever did working 60+ hours a week in the outdoor gear industry. She coaches rock climbing for the local climbing gym, is engaged to be married, and recently bought a house. Life worked out in a big way.

Much of Booth’s story is tinged with irony. She paints the outdoors without naming it, and she’s an avid rock climber who often paints rock, but never paints humans interacting with that rock in any way. She also exclusively paints watercolor—a famously difficult medium—even though she hated it growing up. “I didn't know how to control it,” she explained, “but it was all that was available to me in my apartment during the pandemic.”

Watercolor is often thought of as the “hardest” medium. It’s unpredictable, fluid, and transparent, which makes it difficult to control and correct mistakes, compared to oils or acrylics. But after all those long days painting alone in her apartment, Booth grew to love watercolor.

Part of its appeal is practical, Booth said. Watercolor is hard to control, but it's also cheap and easy to work with. “I can leave my palate and come back to it,” she told me as we sat in her studio. “I rarely ever clean my palate. It's not as toxic as oil. You don’t get all the smells and stuff that you do with oils.”

miscellaneous work, Elaine Booth

It’s also her favorite way to depict the outdoor world. “I love the transparency,” she explained. “With watercolor, the white paper under the pigment is what makes it glow. It gives it a more lifelike quality. The whole thing is filled with white, instead of having to add highlights with white pigment.”

There are many landscape painters who work with the sprawling vistas of the Southwest, the Rocky Mountains, or the Pacific Northwest. The American South, by contrast, is underrepresented. Part of Booth’s hyperfixation on southern woodlands is simple logistics. When she lived out West, she painted the West. Now she lives in the South, so she paints the South.

But she also has a soft spot for the quiet natural splendor of the South, she told me, and figuring out how to depict it appeals to her, as a challenge. “It's hard to paint nature in the South,” she said. “You don't get these big wide open vistas. You get more intimate compositions, because there's more tree cover.” Being born and raised in Alabama, Booth also “wanted to celebrate” her home. (Her family has been in the South a long time. “My last name is perhaps a clue to how long we’ve been here,” she joked. And yes, there is a relation.)

“The landscapes of the South are so worthy of being seen,” she said. “I saw an opportunity, or maybe a responsibility, to fill a gap.”

Booth says that, above all else, she wants her viewers to feel like they are there, when they see her work, wherever there might be for them.

In her artist statement, she references not another watercolorist, or even a painter at all, but Japanese sculptor Isamu Noguchi, and his belief that “play [can be] a purposeful approach to understanding the way we occupy space.”

“As a climber, I am paying a lot of attention to how I occupy space,” she explained. “When a viewer is looking at my paintings, I want them to feel that the space that they occupy in the landscape has meaning. That they can understand their place within the landscape.”

In a world with staunch battles taking place over the use and protection of public lands and wilderness, Booth’s work is perhaps even more poignant. One of her paintings is titled “The Myth of Untrammeled Spaces,” in reference to the Wilderness Act of 1964, a federal land management statute that was designed to create a formal mechanism for designating wilderness.

The most famous line in the text is as follows: A wilderness, in contrast with those areas where man and his own works dominate the landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.

“I called that painting ‘The Myth of Untrammeled Spaces,’ because there's not really any such thing as untrammeled space,” Booth explained. “Land has been used in so many different ways for so many different centuries by humans. Us existing in landscape… I think there's supposed to be a place for that.”

Booth believes rock climbing, in particular, has been a longtime aid in her art, and vice versa. As a climber and coach, she says her exploration of painting has helped her problem-solve on the rock, and coach other climbers, too. “Nothing exists in a vacuum, right?” she said. “Climbing and art, they’re both about purposeful movement. You can’t afford to waste momentum. I’m thinking about where to make marks, as a painter. I'm thinking about how I’m going to move, as a climber.”

Like much of the sport climbing in north Alabama—particularly our biggest local crag, Little River Canyon—Booth favors compression-based, powerful climbing on overhanging terrain. This contrasts with the slow, thoughtful nature of her painting, because speed is paramount, but in both mediums, precision is the chief concern. “I have to be pretty accurate with my moves on the wall if I'm going to make the move work,” she explained. “Watercolor, too, is really unforgiving. You have to make a decision and make the mark. If you make a wrong mark, it's really hard to cover up because, again, the media is transparent. There’s a high degree of commitment.”

Booth’s advice for aspiring artists is fairly sobering (Get a business degree. Get good at marketing yourself on social media.) But she also believes that part of her success is found in her willingness to pull from disparate sources. Her muses come from architecture and sculpture and woodblock printing and other art forms just as much as, if not more than, the world of painting. “There’s a lot of Basquiat wannabes online now, because all they're looking at is Basquiat paintings,” she joked.

She minored in art history at university, which she credits with exposing her to this diverse tapestry of art forms, but she says raw curiosity has served her far more. “More than anything else, it's important to have lots of things that you're looking at,” she said. “Not just one style, one form.”

Booth also spoke to the importance of finding a community. “Nothing exists in a vacuum,” she said. “We're supposed to be a product of the things around us, hopefully in a good way.”

She’s quick to admit that her finances as a full-time artist are certainly modest, and that she’s been buoyed by both her parents, who gave her room and board when she returned from Kansas and was just starting her career, and more recently her fiancé, a salaried aerospace engineer (with a more than reasonable income).

But she said another important thing for any emerging artist or creative to keep in mind—and something she often struggled with early in her career—is the rich value of artistic work, which can be nebulous and often defy quantification. “For a long time, when I first started being a full-time artist, I was really ashamed that I lived with my parents as an adult,” she admitted. “But many of the most well-known authors, famous artists, and other creatives of history, people we’ve looked up to for centuries, they all had patrons, and they weren't ashamed of that. It often takes a community to support important work being made. I feel like I have a great responsibility to make beautiful things that impact people.”

Booth said for all budding creatives, although it's easy to tie self-worth to income, such as how many paintings you’re selling (or in the case of this author, how much you’re making per word for the stories you write), these metrics are misleading. They might reflect your fiscal savvy, but they don’t reflect your worth as a creative, or the impact your work is having.

“When people come into my studio, and they start crying because a piece reminds them of somewhere they went with their dad, that's powerful,” she said.

It might not always be worth money, but it’s always worth something more.

Elaine Booth is a watercolor artist based in Huntsville, Alabama. Her work can be viewed and purchased at her studio (#303) at Lowe Mill ARTS & Entertainment, 2211 Seminole Dr SW, Huntsville, AL 35805 or online at the link below.