Descent from the Roof of the World

Dangerous rapids, hostile Maoist rebels, and living without fear. Darren Clarkson-King on an expedition down Nepal’s treacherous Arun River

The year was 2002, and 26-year-old British paddler Darren Clarkson-King was at a low point in life. “I was working a dead-end job and I was in a relationship that I wasn’t super content with,” he said. “I just wasn’t happy.” At these points in our lives, some of us might turn to drinking, laying around all day watching TV, or going out and getting a poorly-thought-out tattoo. Clarkson-King did what he did best. He started looking for a river to run.

In southern Tibet, there is a river that falls off the back of Sagarmatha, the mountain most of us know as Everest. Snaking north down from Everest Base Camp, past the legendary Rongbuk Monastery, this river, known alternatively as the Rong Chu, Bum-chu, or Zhaga Qu (among myriad other names), flows in a long, twisting loop north and east around Makalu (8,485 m) before winding south into Nepal between the soaring massifs of Makalu and Kanchenjunga (8,586 m), two of the world’s highest peaks. Here, it becomes known as the Arun.

Named after the charioteer of the Hindu sun god, the personification of the ruddy morning glow of the rising sun, the Arun is the largest trans-Himalayan river in Nepal. It also has more snow and ice coverage than any other Nepalese river basin. “It’s a river of myth and legend, even now,” said Clarkson-King. In comparison to the nearby Dudh Kosi, the highest elevation river in the world, the Arun was mostly unknown in 2002. The river had seen a couple of descents, but there was little to no information about it save from a brief description in a guidebook, which mentioned the put-in and takeout points and not much else.

This was exactly the sort of adventure Clarkson-King hoped would bring him out of his funk. He had no second thoughts. “I’d been to Nepal before, I’d done solo first descents, and thought I was quite a big deal,” he said, laughing. “But then, in your twenties, you always think you’re a big deal, and really you’re not, right?”

In an exchange that brings to mind Eric Newby’s famed Can you travel Nuristan, June? telegram to Hugh Carless in ‘56, Clarkson-King fired off an SMS message out of the blue to his good friend Craig Dearing, I want to go on a trip. Do you fancy the Arun? Dearing responded with a blithe, Yeah. The trip was on the books. Dearing enlisted another friend, Robin Lofthouse, and their team was locked in.

To Reach a River

The trio arrived in Kathmandu in the spring of 2002. Already, things had proven difficult. They’d landed in Delhi en-route to Nepal only to find that their boats had been left in Kuwait, then missed their Kathmandu flight and been forced to scrounge plane tickets on the black market just to reach Nepal. After much ado, the airline got their boats flown to Kathmandu, but their journey to the Arun had barely begun.

The three boarded an 18-hour overnight bus headed west, to the village of Hile. There, they hired porters and began a six-day trek north on foot to a small village called Num, which sits just east of the Arun. To avoid carrying extra footwear in his boat on the river, Clarkson-King had only brought Tevas and wore them for the entire trek. “These are long, 12 or 14 hour days,” he said. “It was really hard, hard going.” They slept in local houses and porter stops each night, each day getting further and further from any sort of support.

At the end of the fifth day, they staggered into Num, utterly exhausted. But something was wrong. The village was much busier than it should have been. The team had walked straight into a troop of nearly 250 Maoist guerilla fighters, who were making their way down the valley.

When Clarkson-King and his friends visited Nepal in 2002, the Nepalese Civil War, or Maoist Revolution, was in full swing. The conflict was sparked in 1996 by the Communist Party of Nepal-Maoist (CPN-M), a militant splinter of Nepal’s Communist Party, with the express goal of overthrowing the Nepalese monarchy in lieu of a People’s Republic, and saw over 17,000 killed in a decade of war.

Walking straight into the hornet's nest in Num, the three kayakers were immediately placed under arrest. They were forced to pay the Maoists a “tax” and were kept as hostages while the rebels decided what to do with them. “Some threatening behavior was going on,” Clarkson-King said, chuckling. “A bit of waving AK47s and big knives and that sort of thing. It was nerve-racking.” He paused. “It’s especially more nerve-racking when you decide that, no matter what they say or do, you’re going to go paddle that river.”

The team was kept under house arrest and began prepping their gear that night, assembling their break-down paddles and getting ready for the river. Luckily, the Maoists did a poor job guarding them, and just before dawn the following day, the three men took their boats and fled to the river. En-route, they met more Maoists coming into town, but by sheer luck, these rebels hadn’t communicated with the group in Num and didn’t realize they were crossing paths with fleeing hostages.

The kayakers didn’t stop to count their blessings. They knew full well how lucky they’d been. Clarkson-King, Dearborn, and Lofthouse put into the Arun, and off they went.

Out of the Frying Pan and Into the Arun

The gorge cut by the Arun is one of the deepest in the world and one of the oldest. It existed before the Himalayas. The sheer ramparts of Makalu and Kanchenjunga rise thousands of metres on either side. From what little they knew about the river, the men expected a six-day paddle out from the put-in at Num. The first three days through the gorge would be continuous Class V+ rapids. On the third day, the river reaches a place called Tumlingtar. Here, the difficulty would lessen to Class III and II as the Arun drifted down to India.

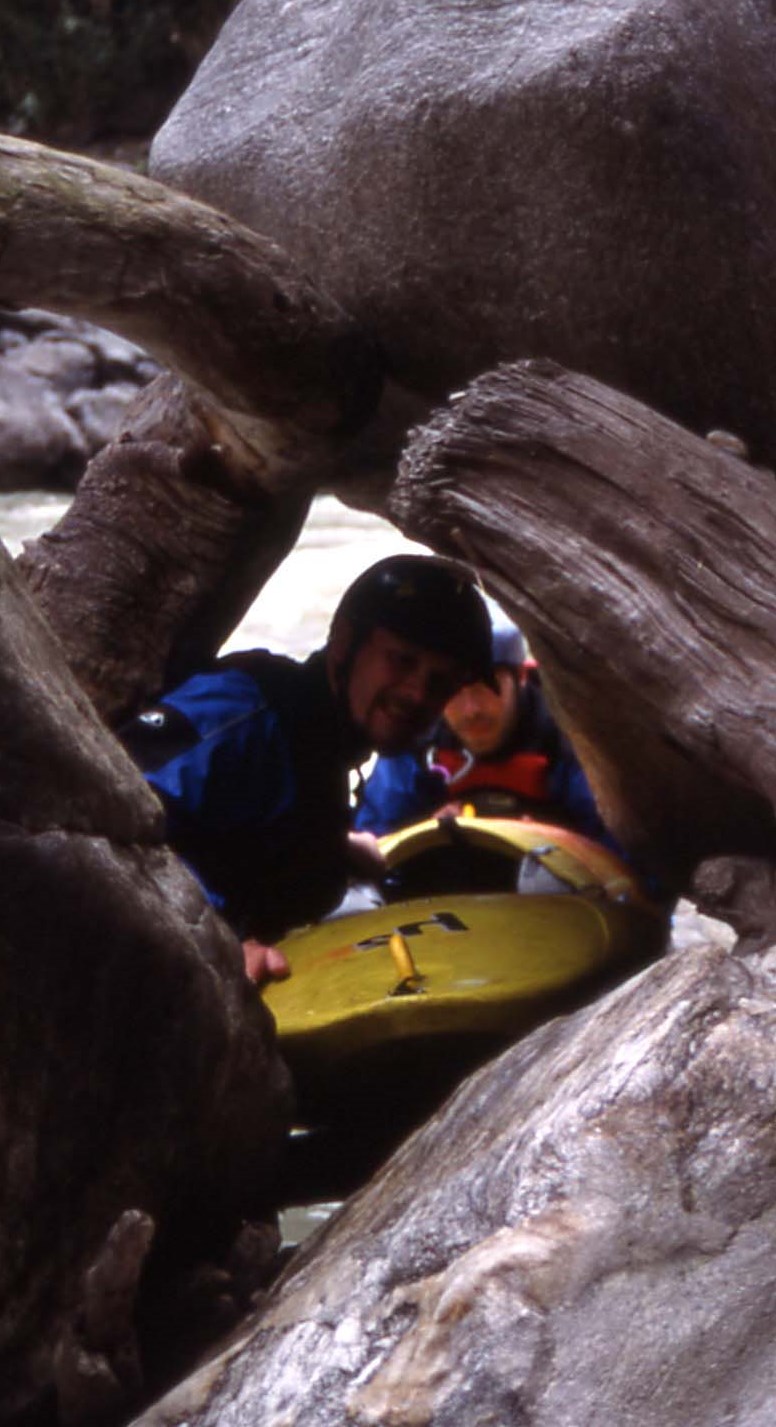

Until Tumlingtar, however, it would be nonstop action, and nonstop Class V/+. Once they put in, there would be no escape. “Basically, you’ve just tied yourself to a freight train,” Clarkson-King said. The men were entering the belly of the beast. “This gorge is a deep, scary place,” he added. “You’re doing really, really committing moves in loaded boats, with no knowledge about what comes next. I could wax lyrical about ‘Oh, the washing machine this..’ and ‘We had to do this crux move...,’ and so on,” he continued, “but it’s just hard. That’s all there is. It’s Class V+, nonstop. It’s really, really hard.”

He paused. “When you jump on the Arun, you just roll the dice at the top and hope you get the results you need.”

Though Clarkson-King had paddled with Dearing before, he had never met Robin Lofthouse before this trip, so I asked him how their team handled these harrowing circumstances, expecting some natural friction. “We just stuck together,” he said. “No question. Though the options to walk a rapid were few and far between, “if one person walked a rapid, we’d all walk it,” he said. “Even if we were able to paddle it, we wouldn't, to keep our morale and team spirit up. I’ve never been on an expedition where I haven’t gotten on well with my expedition buddies,” he added. I pushed him a little here, asking if there was a trick to that, or if he thought there was something intrinsic about his personality that made him easy to get along with, but he just laughed. “It’s quite simple really,” he said. “I don’t have dickheads for friends. If you have a good friend, whose opinion you value, and they bring a third or fourth party, that person’s not going to be an idiot. I’ve never been on a trip where I wished my buddies weren’t there with me,” he said. “I may have wished they’d stop telling the same joke over and over though,” he added.

On the third day, they emerged from the gorge, bruised and battered, leeches under their wetsuits. “It was just a bit too grim, really,” Clarkson-King said, laughing, “but quite nice to tell people about it 20 years later.”

They all breathed sighs of relief as the claustrophobic walls of the gorge began to fade away, and they could see rice paddies and green slopes around them. They had arrived at Tumlingtar, the town that marked their halfway point on the trek in and halfway point on the paddle out. They thought they were home free, but they were sorely mistaken.

Their relief was shattered by the booming cacophony of gunshots. “I remember asking Craig, ‘What do we do?’” Clarkson-King said. Dearborn thought for a moment and responded, “I think it’s lunchtime.” The men waited to hear which side of the river the gunshots were coming from, then paddled over to that side, where the steep walls of the gorge would shelter them from sight. Hidden below the cliffs, they lunched on Nepalese biscuits and water, waiting for the gunfire to die down. After a long period without gunshots, they paddled on down the Arun, into mellower Class III and II rapids. Eventually, the Arun joins the Tamor and Dudh Kosi Rivers before reaching Chatara, where the team put out three days later.

They hired a Land Rover to take a bus to the Indian border, where they caught the last bus leaving for Kathmandu. There was one seat left, and the three were still wearing their paddling clothes. They tied the boats on the roof and stacked onto the bus, cramming into the single seat, and endured a 30-hour bus ride back to Kathmandu.

Arriving in Kathmandu, they learned some startling news. When Clarkson-King and his partners had walked through Tumlingtar on the way up, they’d met an Italian-Spanish climbing party. They learned that the same Maoists who had captured them in Num had continued walking to Tumlingtar (where they’d heard the gunshots) and robbed the climbers naked. The Maoists had then moved down the valley, blowing up a police station and a school, killing a police officer in the process. “We got incredibly lucky. That’s all,” said Clarkson-King.

Living Without Fear and Walking With Tenderness

Since the Arun, Clarkson-King has gone on to accomplish a slew of remote first descents and solo descents around the world. He went on to paddle the Rongbuk section of the Arun (in Tibet), and later returned to solo the Nepali Arun from Num and the Dudh Kosi, becoming the first person to solo paddle all the rivers of Everest. To this day, he is the only person to have paddled all the rivers that flow from both Everest and K2. He also has completed the North American Triple Crown, descents of the notoriously difficult trifecta of the Susitna, the Alesk, and the Stikine Rivers.

Clarkson-King sees paddling as unique in the adventure world because rivers are everchanging. Over time, the weather, flow, and features in a given river can change entirely. “It’s hard to gauge your ability against a medium like that, as opposed to something static, like climbing,” he said.

With so many noteworthy solo and team descents to his name, he also has a unique view on the differences between solo paddling and group paddling. “Personally, I believe when you paddle in a group, oftentimes you’re actually taking a higher risk,” he said. “In a group, you can hide from yourself. When you’re doing anything extreme, whether it be climbing, riding a motorbike, or paddling, you’re with yourself 24/7. Every thought, every emotion, is raw and you have to deal with it. When you’re with peers, those thoughts and feelings are muted, which can be dangerous.” On the flip side, Clarkson-King noted, when you make a bad judgement call in a team, your peers are there to double-check you. When you’re alone, there is no sounding board. “If you’re solo, you have to believe 100% in every decision you make, whether it’s right or wrong. If you have doubt in your decision-making, it’s going to really mess with your head.”

There wasn’t any particular moment on the trip, neither the Maoists or the rapids, that he remembers as scary, years later. “What’s scary is how a trip like that changes your perception of your personal ability,” he said. Without that trip, would he have gone to paddle the Dudh Kosi, gone to paddle in Pakistan, Bhutan, Tibet? Would his life be the same as it is today? He isn’t sure.

Besides, he isn’t someone who believes in feeling fear. “There is no such thing as healthy fear,” he said. “Fear is always bad. It’s the bogeyman under your bed. If you live in fear, you can’t function properly.” Anxiety, on the other hand, is something Clarkson-King accepts as a natural part of high adventure. “No matter how anxious you get, you’ll come out of it. You can live with that.”

In order to avoid living in fear, no matter how difficult or dangerous the river he’s paddling is, he breaks down his expeditions into segments. On the Arun, each three-day section was a segment, then each day was a segment, then each individual rapid and river feature was a segment. “If you break it down, nothing seems like that big of a step,” he said. “The only thing that matters are the strokes you’re making,” he said. “You paddle as long as you need to paddle. That’s it.”

Even traveling to remote locales and foreign lands, he said, is never as scary as it’s made out to be. He travelled to Pakistan after 9/11, and everyone warned him against it, telling him he should be afraid of being robbed or killed. The difference between “people’s perception and his reality,” he said, was quite different. Even with warlords in Pakistan firing AK47s over his head, he never felt personal malice. “It was just a cultural thing, and it was okay,” he said. “It wasn’t about me as a person.”

The most important thing is to “walk with tenderness,” he said. To realize that you’re not that different from the guy making your tea. Respect traditions, respect the traditional clothing, hand gestures, and customs of where you travel, but realize that at the end of the day we’re all of the same heart.

“Everyone on this planet wants a good life,” he added. “Everyone wants to smile, everyone wants to laugh. Remember that.”

A Different World

Things have changed in the 18 years since Clarkson-King and his friends paddled the Arun. He’s 44 now, and the world is a different place entirely, particularly in the realm of adventure sports, thanks to social media and constant connectivity. “Social media gives us instant gratification that what we’ve done is worthy,” he said. “Decades ago you didn’t necessarily tell the whole world about what you did. You might tell your friends, but you weren’t posting for everyone in the world to see.” There was more honesty when it comes to how expeditions can change your emotions and game, he believes. “You weren’t just clicking and posting. You were spending time ruminating on things.”

On the positive side, this interconnected new world has shown people that anyone can go out and explore, which is a good thing, he noted. “It’s lost a lot of the mystique though,” he added. “We used to have amazing mystique. You’d sit around campfires or in bars, hearing a hushed story about a kayaker or climber. Now everyone knows everything. I quite miss that mystique.”

I had one last question. Clarkson-King laughed, then thought for a moment. “If I could go back and tell myself one thing before I ran the Arun….. It’d be that no matter what gets thrown at you: A) It’s going to be a good story to tell when you’re 44, and B) It’s going to be alright. It’s all going to work out.”

-------

Owen Clarke is an outdoor and travel journalist based in Colorado. He is a columnist for Rock & Ice and The Outdoor Journal, and has written for brands and organizations including Petzl, Black Diamond, Arc’teryx, Outdoor Research, Access Fund, and Trango. He also writes for Fiire. Check out his other work here and follow him on Instagram @opops13

Comments ()