Devils Tower: Why We Don't Climb in June

An iconic mountain, world-famous for its presence in 1977 film Close Encounters of the Third Kind. But the mountain holds far greater importance for several groups beyond its cinematic history….

This article was originally published in June 2017.

Mato Tipila, or Bear’s Lodge, a jaw-dropping igneous intrusion rising out of the plains of Wyoming, is a sacred site to a number of Native American tribes, including the Lakota, the Cheyenne, the Crow, the Arapahoe, the Shoshone and the Kiowa. Tribal groups and individuals hold religious ceremonies at Mato Tipila throughout the year and sacred sites pepper the mountain’s flanks.

Devils Tower is also a soaring igneous intrusion in Wyoming’s flatlands, and a world-renowned place for rock climbers. Declared a National Monument by President Teddy Roosevelt in 1906, Devils Tower has hundreds of climbing routes on its columned faces, many going all the way to the top.

The thing is, Mato Tipila and Devils Tower are one and the same. The reverence with which both groups treat the 867-foot-tall formation—a spiritual one by Native Americans, and a recreational one by climbers—has led to friction over the years. A voluntary June climbing ban, instituted in 1995, has been a sticking point for many in both communities as they try to make the best of a situation in which there will always be less-than-satisfied parties.

Discussion and debate over the voluntary June closure flares up in online climbing forums like Mountain Project virtually every year. 2017 is no different. Complaints from climbers range from feeling unfairly targeted to not understanding why the ban isn’t simply mandatory. But disgruntled parties aside, the June closure represents a good faith effort on the climbing community to respect Native American traditions and cultural values.

In light of the public lands issues that have been in the news so far this year (in particular that concerning Bears Ears National Monument in Utah), it's worthwhile to examine the complexity of access issues around another National Monument.

The origins of the tension between climbers and American Indian tribes at Devils Tower date back to at least the 1980s. Lucas Barth, a National Park Service (NPS) Climbing Ranger at Devils Tower, explains, “The National Park Service had received complaints from tribes about climbing since the 80s. They thought it was disrespectful to their sacred site."

In 1990, driven by rock climbing becoming a mainstream and popular recreational activity, the NPS directed all park units with significant climbing activity to develop a climbing management plan. In 1995, after several years of contentious development, a final Climbing Management Plan (CMP) was published for Devils Tower. The CMP was drafted with input from representatives of the National Park Service, two Native American Tribes, the Access Fund, and the Black Hills Climbers Coalition, and sought to present a compromise that would preserve climbing access and address the wholly legitimate grievances raised by the Native American tribes

Mato Tipila is an extremely sacred place for Native Americans, and the CMP addressed this directly:

Some American Indians perceive climbing on the tower and the proliferation of bolts, pitons, slings, and other climbing equipment on the tower as a desecration to their sacred site. It appears to many American Indians that climbers do not respect their culture by the very act of climbing on the tower. Climbing during traditional ceremonies and prayer times is a sensitive issue as well. Elders have commented that the spirits do not inhabit the area anymore because of all the visitors and use of the tower, thus it is not a good place to worship as before.

The CMP ultimately included elements such as no new fixed anchor installation and the permitted replacement of existing fixed anchors to limit resource impacts. It also introduced the voluntary June closure for climbers, which was supported by the tribal and climbing representatives as a sign of respect for the cultural significance of the Tower to tribes, and to meet the climbing community's request to self-regulate.

The problem since then has been the inability to enforce a voluntary ban, precisely because of its optional nature. As such, despite a majority of the climbing community happily choosing to observe the climbing ban, the number of climbers in June has been trending upward in recent years.

The last year before the ban went into effect saw 1,225 climbers on the Tower in June. That number dropped precipitously to 167 in 1996, but has has slowly crept up since then, year by year. In 2016, 374 people climbed the Tower in June.

“From our point of view,” Barth says, “a successful June ban is one in which the number of climbers is equal to or less than the year before.”

Some of the more commonly cited sticking points by climbers that take issue with the June ban are that it only applies to them and not to other hikers, that having it occur in June—at the height of the climbing season—is arbitrary, and unnecessarily inconvenient.

Barth notes about the first: “I don’t know why people hang up on that. Hikers aren’t affected because American Indians don’t feel that hiking around the Tower is a desecration to its sacredness. They specifically feel that it is the act of climbing—including bolting, and pitons and webbing—that’s the desecration.”

As for the June timing, it is far from an arbitrarily chosen month. While they are held throughout the year, the highest concentration of ceremonies occurs in June. This is because of the Sun Dance Ceremony and the summer solstice, according to Barth. Furthermore, it is easier to encourage a ban in a single month versus scattered periods of time throughout the year.

In an email to The Outdoor Journal, Tim Reid, Superintendent of Devils Tower National Monument, explains the thinking behind the voluntary closure:

The 'voluntary' aspect can seem awkward and abstract. But it actually embodies a code of honor, conduct and intent: The tribes wanted climbers to want to 'voluntarily' respect June as a set-aside month, and climbers vocally wanted the chance to show that they can self-regulate. The self-regulation component was the sole reason that the Access Fund supported, and continues to support, the June voluntary closure.

Ultimately, refraining from climbing for one month out of respect for those who first inhabited the area is beyond reasonable. It is important to note, again, that most climbers willingly abide by the ban.Most comments on the Mountain Project forum are fully in favor of it.

One poster on the Mountain Project thread wrote something noteworthy.

“I'm fully in support of making the [June] closure mandatory and punishable with a fine. Seriously, we close climbing in some areas for half the year for birds, but we can't close this thing down for one month? And if we did close it down, who's being affected?...300 people...”

But those 300 people, at least for now, besmirch all those trying to do right. Some of those who climb in June are guided parties; some are unaware of the voluntary ban; some simply don't care, and perhaps just feel the need to be contrarian and assert their disregard for authority. Regardless of the reasons, malicious or not, climbing the Tower in June is disrespectful to the beliefs of American Indians. It also puts future climbing access at the Tower in jeopardy.

Though voluntary, the ban should be treated as mandatory for all intents and purposes for both of these reasons.

To learn more about Mato Tipila/Devils Tower and the June closure, visit https://www.nps.gov/deto/index.htm.

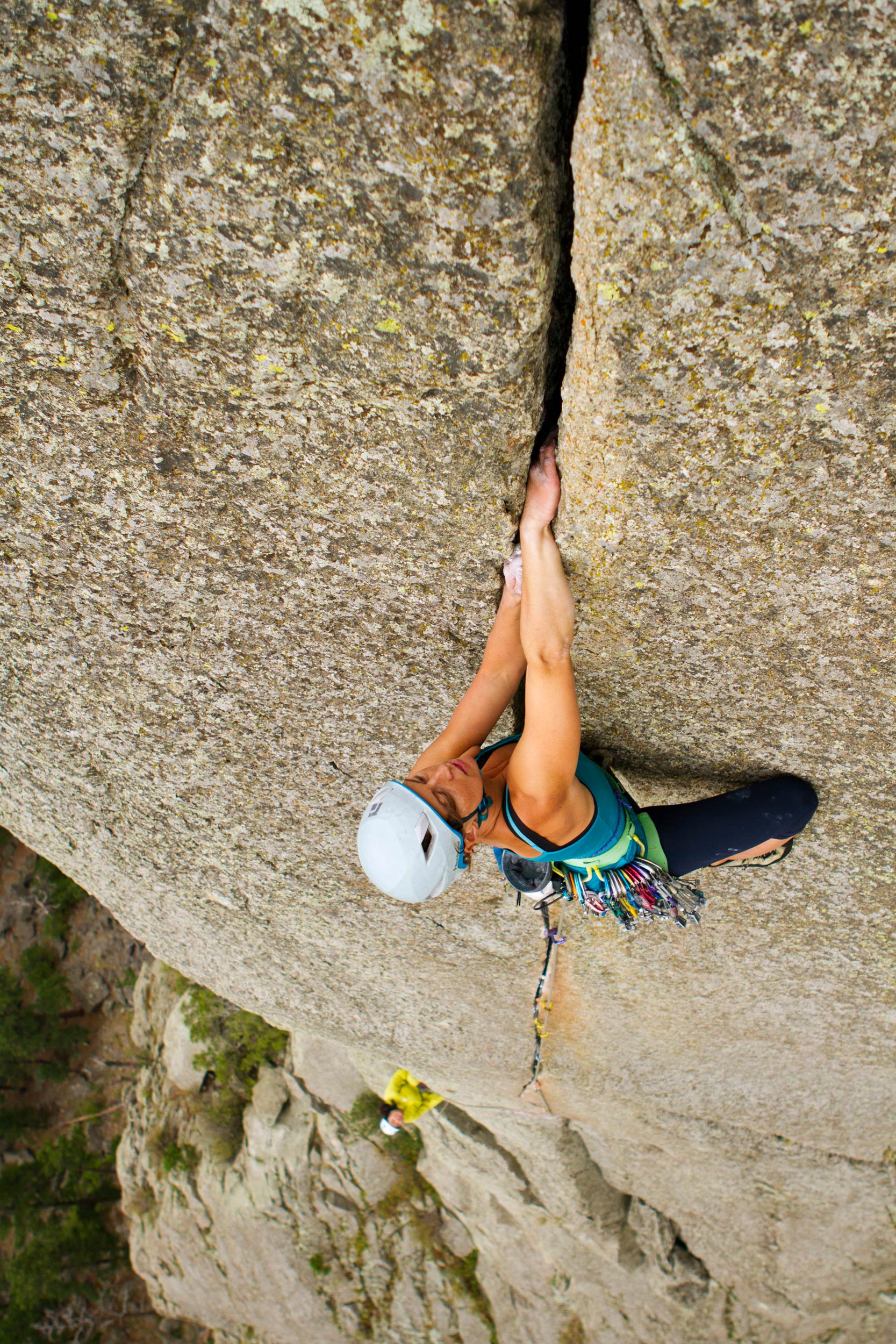

Feature image: Devils Tower. Photo: Lucas Barth.

Comments ()