In the age of rapidly evolving outdoor sports, athletes deal with injuries while simultaneously growing faster, fitter and stronger. Their bodies are like fingerprints, a balance of its nature versus the nurture it receives. What dictates the course of their bodies - musculoskeletal injuries, diagnosis and learning?

Vibram USA – a barefoot running footwear company – was sued in early 2012 for asserting that their shoes reduce foot injuries and progressively strengthen foot muscles. A long debated topic of discussion – barefoot versus shod running – has gripped both scientists and athletes for decades. Yet, all practitioners of the sport regularly face befuddling injuries; some because of the nature of the sport itself, while others due to the lack of a proper form.

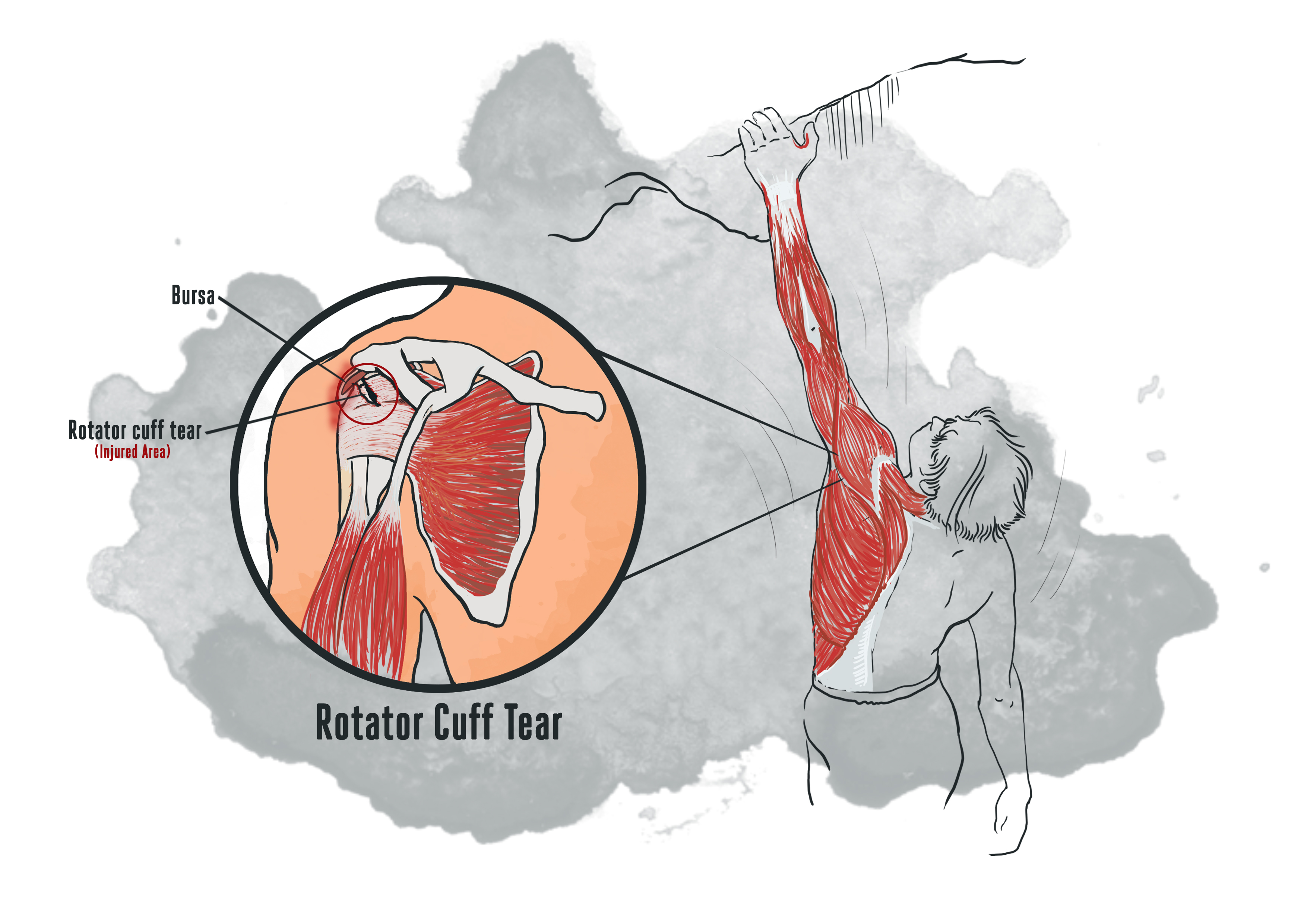

I was ignorant of this fact five years ago, when, while practicing a different sport altogether, I heard the sound of a muscle stretching irregularly as I jumped for a Dyno.

A Dyno – in climbing parlance – is a dynamic movement to leap across a blank section of rock to grab a hold that is otherwise out of reach. This looks simple with enough grace but masks a volley of internal forces, sometimes outrageous in magnitude.

The silence in Fontainbleau was overwhelming. Laying on a crash pad, in the epicenter of outdoor European bouldering, I reflected on the consecutive winters spent inside climbing gyms, training regularly for any outdoor adventures.

Once back in the Netherlands, I visited a doctor, who diagnosed me with an inflammation of the rotator-cuff. She advised me to train my shoulders for at least a month before I started climbing again. I inquired about the extent of the injury and wondered how it could have been avoidable.

First, let’s talk about Danny Way. Unless you are a skateboarding enthusiast, it is hard to put a face to that name. In 2005, he jumped off a ramp to clear a 19-meter (62.34 feet) gap at The Great Wall of China. This is no ordinary feat in itself but most of the world, at that moment, was oblivious to a tiny piece of detail. His steering foot was smashed and his knee had broken mechanics at play. In addition to living through this incomprehensible attempt, Way threw a 360 in mid-air. He then did it five times over. The amount of force a human body would experience standing on earth was quadrupled in Way’s case.

In comparison, a dyno demonstrates negligible force.

Every so often, in climbing gyms scattered around the globe, teenagers crawl through overhanging 7c (5.14 in US terminology) routes, exerting much more force on their bodies than a mere dyno would. Today, they have abundant resources, controlled environments, thoroughly robust exercise regimen and dogged food habits. Alternatively, I started climbing much later in life; when my body had already set up limitations on its abilities following a lifestyle that barely involved any stretching.

My recovery and subsequent physiotherapy after the episode in France made me realise the nature of my body. The truth, at least for most of us with a sedentary lifestyle (coupled with demanding athletic endeavours), is that our bodies are accustomed to being at rest. We spend, on average, a third of our lives sitting, a third sleeping, and maybe a minor fraction of the remaining third indulging in very demanding athletic activities. It is conceivable that such extreme forces may make us prone to injury on occasion.

Musculoskeletal injury is one of the primary hazards of industrialisation where normal body movements are occasionally compromised by regular lifting of weights. Dr. Kathryn Sophia Stok – a lecturer at the Biomechanics laboratory of ETH Zurich – asserted in one of her lectures, “Muscles are a core element of strength,” in an attempt to reiterate how important muscle forces are in the study of Orthopaedic Biomechanics.

Our muscles are made up of basic rod like units called myofibrils. It is the contraction of the myofibrils that generates the force a muscle produces. We can train our neural pathways for better contraction of muscles to exert more force. A child’s brain learns faster and adapts muscle contractions quicker to the task they are performing. Have you tried learning how to ski at the age of twenty-four? Kids aged four or five are much faster and more comfortable at learning this sport, or for that matter any exacting sport.

The same myofibrils allow professional climbers like Alex Honnold and Ashima Shiraishi to warm up on menacingly flat pieces of rock, habitually. Honnold is thirty years old. Shiraishi, as the The Guardian reported in March 2015, became the first female to climb a 9a+ route (5.15a in US climbing terminology). No female has ever achieved such a feat earlier. Shiraishi is only thirteen years old.

Let’s try a different perspective, one that doesn’t excuse the older generation. How is it that Dean Karnazes (aged 52) runs through the warmest conditions known to man and Will Gadd (47) climbs overhanging ice walls in sub-zero temperatures? Just in case our standards have already digested the potential of these outdoor athletes, Kilian Jornet is attempting to “run” up Everest in 2015.

These athletes neither have a different bone structure, nor are they dictated by special mechanics. So what explains this spectrum of physical variation? Our musculoskeletal system is like a fingerprint; everybody has one, yet each is a story of its own. The environment individuals grow up in, their eating habits, physical routines and medical histories are all factors that shape this story. It is the same set of bones, tendons, ligaments, muscles and cartilage, packed up in a personal experiment of nurturing.

Locomotion is one of the cardinal functions of our musculoskeletal system. Tissue component surrounding the tendons allows us to move our limbs with ease avoiding any excess stress on them. Tendons control the movement of muscles by connecting them to the bone. Whereas, ligaments keep the bones in place by connecting them at joints preventing unreasonable movement of our body parts. This intricate network of bones and surrounding tissue works in perfect synchrony.

A disruption of this locomotor system can turn a privilege like walking or holding a glass into the most arduous task, especially during old age. Reflect on a senior member around you who may be suffering from Osteoporosis. This condition results in weak bones that are more prone to injury. Osis – degeneration of tissue (collagen fibers in this case) – results in the bone and tendons around the bone to degrade in their tissue component. In contrast, itis – inflammation of a tissue – is the body’s response to an injury to muscles, tendons, ligaments, cartilage and bone itself. Sometimes, longer periods of wear and tear of our joints or tissues (leading to repeated inflammation) cause chronic damage and ultimately, degeneration.

Inflammation of muscles or tendons is common among climbers and runners. How many times have you landed wrongly on your strong foot while bouldering or running along the trails? Once an injury occurs, the first step to dealing with it is to form a diagnosis. The frequently occurring ones become common terms of use and are often used incorrectly. For instance, the difference between a strain and a sprain. Muscles and tendons can be strained upon stretching. Tearing or stretching of ligaments is called a sprain.

When we abruptly land on our foot and hear a snap, it is associated with a sprain. The ankle, along with a multitude of ligaments to support the joint, also has attachments to the tendons of the muscles of the leg. Hence, as non-practitioners of medicine, we do not have enough knowledge and experience to point out the difference. Doctors try to do their best to diagnose the problem. Its success depends on how accurately we dictate our medical histories. Once the diagnosis is confirmed, spotlight shifts to repair and rehabilitation, which depends on adequate treatment given in time with proper follow-up and patient compliance.

All the examples of extraordinary physical prowess (despite injuries) commence from a single point – Learning. Even if evolution is understood down to its very ingredients, we have to depend on our learning abilities. This learning process of our brain put simply, starts with imitation. As a child, we have seen our neighbours “jog” with bent vertebrae, landing on their heels. The runners among us start running like that trying to naturally correct their form. But sensory feedback in running is delayed (most often until after injuries) because we have worn “comfortable” shoes all our lives. In contrast, the Tarahumara people, a tribe settled in the high sierras of Northwestern Mexico, who run barefoot, have different biomechanics. As is clear from the text of Born to Run, a book written by Christopher McDougall, to this day they are faster and fitter than most ultramarathon runners in the world.

In this epoch of accessible climbing gyms, we learn to mimic all kinds of climbing habits. A larger gym-climbing population crimps on small holds with a closed hand grip, the thumb covering the fingers, acting as a lock to avoid any slipping. This is the fastest way leading to injured fingers. “The correct way of doing this, with open handgrips where the subjected force is the least, is often ignored as it takes months of patience to develop such a style of climbing,” Doctor Schweizer told me.

I was sitting in his office – bereft of any expectation– with a folder of my past diagnosis, and a taped finger. A different but old injury had restricted me from climbing regularly. After my blasé narrative, Dr. Schweizer asked me to remove the tape and prepare for an ultrasound, the first in a year of visiting doctors across three continents. A finger pulley injury – a tendon related injury often attributed to climbing – had left me with an awkward feeling in my hand. The ultrasound indicated that everything was intact. I didn’t believe him, skeptical of having countless unsatisfactory opinions and therapies. He smiled and said, "You shouldn't stop climbing." As a hand surgeon of Swiss origin, he has a rather unconventional manner of dealing with his patients. Perhaps because he is a climber himself.

Dr. Schweizer has been climbing for more than two decades, something I realised when he first shook my hand. He showed me the results of our radiology examination. I was surprised to notice that a layer of collagen fibers, maybe three times as thick as mine, had developed around his fingers. He correctly pointed out that I must have started climbing four years ago back then. These fibers take time to generate, and progressively add to the strength of our hands.

In later life, I am attending a lecture in orthopaedic biomechanics. After a series of injuries that I have tumbled through since France, the inevitable consequences of the sports I indulge in are now transparent. Mikhail Baryshnikov, cited as one of the greatest Ballet dancers in history, says, “The more injuries you get, the smarter you get.” A lot of people have never studied the mechanics of their bodies and still manage to avoid unnecessary injuries.

By sixteen, Honnold was doing one-finger pull-ups. Steph Davis, prior to discovering her passion at eighteen and becoming one of the strongest female climbers in the world, religiously played a piano while growing up. Dean Karnazes quit his corporate job at thirty to add more running hours to his life. Mandy-Rae Cruickshank has gone deeper than most across oceans around the world, without supplemental oxygen. Jeff Clark surfed the Mavericks alone for fifteen years until others discovered it.

These are mind boggling feats performed by individuals who have spent a better part of their lives perfecting the art of balancing mind and body, learning to demand just enough of themselves, which makes them achieve what seems impossible but have the wisdom to stop when damage outweighs performance with long lasting repercussions. Yet, there is one thing in common for all of these outdoor athletes. Injuries. No one escaped them.

This article was edited by a practicing medical doctor for any inconsistencies.