The Aboriginal “Wild”: Tackling Conservation in Tasmania’s Takayna

In the battle for takayna, the Aboriginal name for the forests, is rooted a cry of cultural and social endangerment that calls into question our basic ideas about conservation and wilderness.

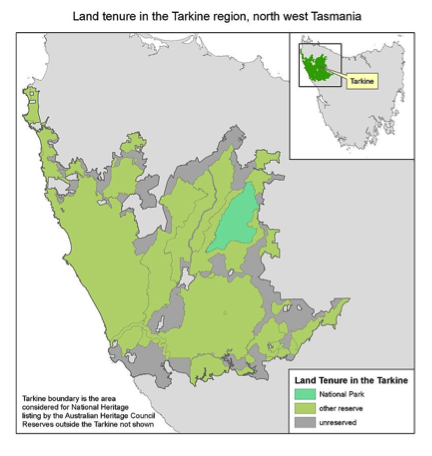

Tasmania, an island 45 minutes off the coast of mainland Australia, bears little congruity to its parental landmass or anywhere else on the planet. Its northwest flank is ornamented by the cool, temperate rainforests of the Tarkine, or “takayna” in the language of the Aboriginal palawi kani (Palawa) people. This biome is a Paleocene relict of the Gondwanan supercontinent and plays host to the epoch’s astonishing evolutionary prowess. Swathed in takayna’s primordial Myrtle trees and man ferns, a salmagundi of endangered endemic species thrive, including the notorious Tasmanian Devil and the charismatic giant wedge-tailed eagle. Steeped in the cool mist of condensed ocean air is a vibrant ecosystem replete with both ecologic splendor and aboriginal relics. The Palawa Aboriginals lived in a reverential symbiosis with their environs, and early 19th century English colonists at least marvelled at the astonishing natural diversity before they began whaling, mining, and logging that splendor.

a preview of the “environment vs. economy” dichotomy of the region’s strife.

Though takayna enjoyed 60 million years void of humanity, the forest’s history is incomplete without an exploration of the area’s 40,000 years of anthropocentric stewardship. But mainstream coverage of the 20th century’s “forest wars” pits the virginal jungle against a monolithic entity of plunder-for-profit, an oversimplification that stonewalls a radical conception of cooperation in the Tarkine.

Emphatic environmentalists decry extractive industry in the Tarkine as a prime example of human intrusion on a vulnerable wilderness. “Greenies”, as they’re dubbed by state officials, protest mining, logging, and off-road motorization in the heart of the contested ecosphere. Australian prime minister Tony Abbott has likened “Green ideology” to economic stagnation. His comment is a preview of the “environment vs. economy” dichotomy of the region’s strife.

Decades of state and Greenie embitterment comprise takayna’s “Forest Wars”. The Tarkine’s official website outlines specifics of the conflict. In 1973, Tasmania’s Forestry Commission commenced a harvesting campaign on State Forest land south of the Arthur River. Operations expanded, and with them, the need for roadways through tracts of protected land. Opposition to a Timber Tasmania road resulted in a temporary suspension of activities under the Labor-Green Accord of 1989. Despite growing support for World Heritage listing of the Tarkine throughout the 90s, the half-finished “Road to Nowhere” was given the go-ahead to recommence construction. Over 100 locals, Aboriginals, politicians, and environmentalists were arrested in an ensuing slew of protests.

"a blanket heritage listing of a region that would stop further growth in an industry that will underpin the economic benefits and opportunities of our state”

The “Road to Nowhere” lost claim to its namesake, but the protests did catalyse awareness of the indelible natural and cultural value of the Tarkine. The Australian Government placed the area on the Register of the National Estate in 2002. While the formal recognition was one step in the right direction, Tasmanian state government has since oscillated in its commitment to protecting the contested lands. Labor Tasmanian Premier Lara Giddings expressed in 2013 that “The last thing we want to see is a blanket heritage listing of a region that would stop further growth in an industry that will underpin the economic benefits and opportunities of our state”. And a recent piece of legislature, 2014’s Forestry Act, revived tensions by outlining a plan to unlock 400,000 hectares of high-conservation-value forest to fulfill a pulpwood quota set and subsidized by the state government. The move was intended to resuscitate the declining timber industry, which has provided jobs to Tasmania’s poverty-stricken rural population. Tasmania’s Liberal party resources minister Guy Barnett says cutting production would result in the loss of “up to 700 jobs” in communities with traditionally high rates of industry employment. “Big Timber” is fighting to retain its place in the Tarkine and communities are reliant on logging jobs. It’s a situation consonant to myriad others in the States, where traditional blue-collar employment has diminished, locals are left scrambling for livelihood, and environmentalists vilify the industries who have traditionally provided jobs.

Traditional Euro-American “Edenic wilderness discourse” eschews the idiosyncrasies of the situation; the notion that cities and human activity are antithesis to nature ostracizes the rural communities who both depend on timber jobs and love the rugged Tarkine. These stakeholders have an economic and emotional claim to the region, and they deserve a revitalized role in the debate. But the reality is, the region’s timber and mining groups are no longer sources of wealth and employment without significant government assistance. A report by The Economist noted that in 2014, Tasmania’s timber industry employed just 4,000 people compared to the 6,000 employed in 2008. Sustainable Timber Tasmania’s 2016 annual progress reports revealed a net loss of nearly $67.4 million, prompting a complete operation overhaul and state-sponsored woodchip quota. To contend with the decline of timber jobs, ailing communities must diversify economically. For now, with heavy subsidies, Sustainable Timber Tasmania will continue to produce an enforced minimum of pulpwood for production’s sake.

The economic decision-making framework has been top-down and informed by traditional industrial land-use priorities. This model effuses the testimony of generations of Aboriginals who inhabit the Tarkine. A contemporary aim of conservation in the Tarkine is to make salient the Indigenous narrative.

“We don’t have a lot of faith in [the government’s] respect for Aboriginal heritage”

Why is the Palawa outcry muted in the concatenation of takayna conflict? Due to contemporary bias and a history of oppression and eradication, Aboriginals are often portrayed as powerless and exploitable. English colonization in the 19th century disposed Tasmania’s aboriginal Palawa people of their land and life. Just a smattering of Palawa survived the incursion of English colonial interests and subsequent genocide, but their claims to their ancestry were often delegitimized. Today’s descendants battled discriminatory policies throughout the 20th century that forced assimilation and denied cultural autonomy.

Despite deliberate cultural subordination, Aboriginal leaders are some of the most preeminent and unremitting in the fight for the Tarkine. But even when Palawa are included in conservation efforts, the multiple-use ideology of sustainability in takayna fails to adequately address indigenous concerns. For example, the Office of Aboriginal Affairs critiques Eurocentric archaeological conservation criteria, which prioritize protection of site-specific, tangible artifacts. According to the group, this approach dilutes the interconnectivity of specific artifact sites and may exclude modern Palawa from unfettered access to their traditional lands. Heather Sculthorpe, executive officer of Tasmanian Aboriginal Corporation (TAC), Tasmania’s chief indigenous community body, summarized overall sentiment in her remark that “We don’t have a lot of faith in [the government’s] respect for Aboriginal heritage”. She made the comment in response to a 2015 draft plan of a “joint management arrangement” whose creation she felt betrayed earlier agreements by rezoning parts of the World Heritage Area for private development and logging.

an engrained harmony with Tasmania; the Palawa incantate that “the land owns us”

The Australian Heritage Commission recognizes that “indigenous custodianship and customary practices have been, and in many places continue to be, significant factors in creating what non-indigenous people refer to as wilderness.” The Aboriginals shaped the Tarkine, and evidence of that heritage percolates the landscape. Bill Gammage, professor at the Humanities Research Centre at the Australian National University, has researched Palawa land stewardship. Isolated on Tasmania since 8,000 BP, native peoples stratified vegetation, quarried spongolite stone, cleared undergrowth, and burned systematically in a complex, cohesive management system. Gammage notes the synergic ethos of the Aboriginals; they were hunter-gatherers, luring choice animals and managing an ecosystem in accordance with geographic rhythms. Greg Lahman of the Centre for Tasmanian Historical Studies asserts that their ontology reflects an engrained harmony with Tasmania; the Palawa incantate that “the land owns us”. Remnants of their stone tools, shell middens, and other cultural artifacts habituate the Tarkine’s wind-swept coastline.

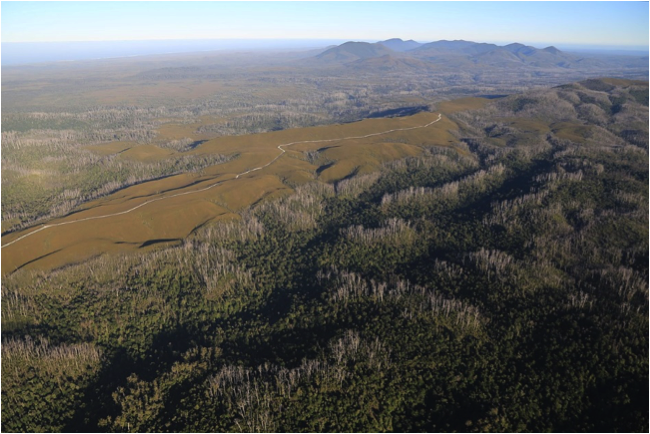

By comparison, Sustainable Timber Tasmania and other local operations are supported not by Indigenous knowledge of optimal ecological cycles, but by government subsidies. Sustainable Timber Tasmania publicizes their corporate documents, and their library makes palpable their prolific research on forest areas of high conservation value. But corporate documents also admit that “the dieback and death of trees and the lack of regeneration in the rural landscape… continues to be a matter of concern since it was first raised in the 1970s”. This dieback is associated with the company’s primary strategy of old-growth clear-felling. Monitorization of environmental impact, including the implementation of an ecological research site, are clearly a high priority—the industry has a vested interest in long-term productivity. According to another document, company research, often in collaboration with other state agencies, has “optimized the benefits to the public and the State of the non-wood values of forests’”.

But what about Indigenous input? Entrenched in the collective Palawa experience is a land-use ethos developed over 20,000 years of Tarkine stewardship. Co-management of land-use decisions between all players in the Tarkine diversifies and dynamizes conservation by prioritizing social justice, sustainability, and cooperation in the legislative process. Without Indigenous consent, logging in the Tarkine is a contemporary incarnation of the colonialist activities that devastated native peoples 200 years ago.

The Tarkine plays host to both unbelievable biodiversity and unprecedented opportunity—the opportunity to redefine this “wilderness” as an ecosystem of man and environment. Collaboration between all stakeholders would include marginalized Palawa, local workers, environmentalists, and state government. A sustainable conservation will require a shift from traditional multiple-use state policy. Contemporary state legislation channels vast monetary resources into an ailing industry by mandating the lumber quota. Justification for this policy rests largely on the employment of rural Tasmanians on lumber mills. But there are other ways to address unemployment than mandating woodchip minimums; environmental degradation should not be the only viable employment avenue for rural Tasmanians. Transformative policy could invest research and subsidies into diversifying living-wage jobs. Bob Brown of the Bob Brown Foundation, a nonprofit group deeply involved in the fight for Tarkine protection, suggests that eco-tourism has potential. “This is not 1950. This is 2018 in Tasmania, which is trying to become a world icon for eco-tourism,” he expounds. Brown contends that employment solutions that rely on infinite productivity of a finite resource are ultimately unsustainable. Finally, progressive reform must explicitly recognize the legacy of environmental violence against Aboriginals and shape policy to reflect the concerns of the least advantaged of Tasmania’s population. TAC spokesperson Lisa Coulson opines that governmental processes “must have Aboriginal community decision making at its core, but that is exactly what is still lacking in Tasmania”. Tarkine management should prioritize the livelihoods of affected parties, not a woodchip surplus; after all, the common denominator in all stakeholders is a dependence on takayna.

Cover photo: Arthur Pieman Conservation area The Pieman River Tasmania. Helen Pearly

Comments ()